Moving Across a Stylistic Continuum

Tambrin Music in Tobago

Andreas Meyer

[1] Experiences and questions

In the early 1990s, I first heard a record with music from the Lesser Antilles edited by Swedish ethnomusicologist Krister Malm.[1] One piece from the island of Tobago,[2] referred to as a “reel”, captivated me particularly. It had nearly nothing in common with British dances of the same name.[3] A violin repeatedly played a short melody with many double stops and a low scratching sound. Parts of the melody were taken up by a singer in a similarly repetitive manner. Furthermore, some tambourines and a triangle could be heard. Only one of the tambourine players, who according to the accompanying text of the record also sang the tune, varied his part in several ways. The volume of his playing was dominating and pushed the part of the violin into the background. The concept of musical interaction seemed related to African percussion music where ostinato patterns are often connected with the variable play of the “master drummer”. In analogy to this, the accompanying text mentioned “Africanised versions” of the reel and the jig in connection with “ghost” and “jumbie dances” where dancers are possessed by the spirits of medicine men. Melville Herskovits’s idea of cultural blend as a form of reinterpretation according to which “old meanings are ascribed to new elements” or “new values change the cultural significance of old forms” (Herskovits 1956 p. 553) was apparently realised here in an almost paradigmatic way. African Caribbean musicians reinterpreted European dances in two ways: musically, they changed forms of interaction, melody lines and intonation, and contextually, they embedded the dances into religious environments. Thus the music proved to be very different from other musical forms of European origin, like for instance the contra dances and quadrilles various authors have described in many Caribbean regions (i.e. Guilbault 1985; Philipp 1990 pp. 58–77; cf. Manuel 2009).

With these impressions, I travelled to Tobago in 1995 on behalf of the Ethnological Museum in Berlin to record samples of this genre, commonly referred to as “tambrin music”.[4] According to several musicians, there were five to seven tambrin bands on the island but only three violinists. Some of the groups therefore used a diatonic harmonica instead of the violin. I got in contact with three bands from different villages the music of which I recorded on video during specially arranged sessions:

- Caterson Tambrin Band (in the following: “Catersons”)

- Pembroke Folk and Cultural Performers (in the following: “Pembroke Performers”)

- The Rising Youth.

Caterson Tambrin Band, 1995. Photo: Gabriele Meyer-Hoppe.

The Catersons and The Rising Youth were pure tambrin bands, the Pembroke Performers an ensemble that also presented other genres on stage, including different drumming styles and “Stringben Music” with guitars and tea chest bass. During the recording sessions the groups played pieces referred to as jigs and reels almost exclusively. The Rising Youth had a harmonica as melody instrument; the two other groups used a violin. The impressions I had received from Krister Malm’s recording was largely confirmed even though the violinists hardly performed double stops. They used a technique of playing close to the bridge and pressing the strings strongly. The resulting scratching sound was low and often drowned out by the drums. Melodies were short and repetitive. The playing of the lead drummers, who frequently varied their patterns, was always dominating. These provisional findings were later confirmed by several musicians. For instance Wendell Berkley, the leader of the Pembroke Performers, described the drumming as the “important part” and the melodies of the violin as “fills” (interview 1995).

My considerations in 1995 were based solely on music played during the arranged sessions. There were no other opportunities for performances during my stay (mid February until the end of March). However, some musicians mentioned weddings, healing ceremonies, folklore festivals, and tourist events as potential engagements. The majority of the protagonists were at an advanced age. Their art had obviously lost social importance. Hence, in the liner notes accompanying a CD later published by the Ethnological Museum in Berlin, I called tambrin music a “dying genre” (Meyer 2000 p. 226).

To review this development I travelled to Tobago for a second time in 2005. Indeed many things had changed. The Pembroke Performers’s violinist, George Charles, had died, as had Van Dyke Baley, a violin player I didn’t meet in 1995, but who was considered an important protagonist. Rawl Titus, violinist of the Catersons, had moved to Trinidad in the meantime. The Catersons had stopped playing and the Pembroke Performers had removed tambrin music from their programme. However, there were some new violinists on the scene: Gary Cooper, who had played the harmonica for The Rising Youth in 1995; Laurence “Wax” Crook, an all-round musician well established in the cultural life of the island; and a young man named Seon Forde. Forde had learned to play the violin from the late Van Dyke Bailey. Cooper and Crook had taken classical violin lessons for three months, learning the basic playing techniques before they started to compile a tambrin music repertoire. “We had to sustain culture, the indigenous music, tambrin music. So I had no other choice but to fall in and do a thing with the violin”, Lawrence Crook said in an interview. Furthermore, a new generation of drummers were on the scene. Altogether four bands were performing in 2005 (the same is true at the time of this writing in 2011):

- Mount Cullane Tambrin Band (in the following: “Mount Cullane”)[5]

- Unity Folk Group (in the following: “Unity”)

- Professional Cultural Group (in the following: “Professionals”)

- Royal Sweet Fingers (in the following: “Sweet Fingers”).

The villages of Les Coteaux, Golden Lane, Culloden and Mount Thomas, located close together in the north-west upland area, formed the centre of tambrin music in the past and continue to do so in the present. The musicians mainly belong to a few related families.[6] While the Sweet Fingers play alone most of the time, the other bands are connected with dancers from the same area. Unity, Professionals and Sweet Fingers have a violinist in their midst, Mount Cullane is the only group that normally uses a harmonica.

In 2005 I heard the bands playing not only at recording sessions but also at rehearsals and concerts for tourists. With the new generation, the music appeared different. The violin players had a sonorous and clean sound, always dominating the ensemble playing. This impression was heightened when the music was amplified on stage, since it was nearly always mixed in such a way that the violin was in the foreground. Often the part of the lead drummers could only be followed when listened to intently. To some extent, the drummers played rather cautiously and with fewer variations than their colleagues did in 1995. For me this development led to two central questions:

– firstly, whether I could find clear and comprehensible causes for the changes (I assumed that a rising significance of stage presentations would be important here, cf. Meyer 2006 pp. 32–33),

– and secondly, whether these changes could be considered a new concept of musical interaction, a profound and basic transition from percussion music with a juxtaposition of ostinato patterns and a mutable part of the leading drummer to a form of interaction in which melodies take the leading part.

With these questions in mind, I again travelled to Tobago in 2008 and 2009.[7] The journeys were carried out in July and August respectively, when the annual Tobago Heritage Festival regularly takes place (with stage presentations involving tambrin music). During the festival events the groups Sweet Fingers, Professionals and Mont Cullane were recorded on video. Furthermore, I had the opportunity to attend performances of tambrin bands beyond stage presentations, a wedding lasting two days and a harvest festival of a Spiritual Baptist Church congregation. In addition, I recorded the music of the groups Unity, Professionals and Mount Cullane at video sessions, including different subgenres.[8] It was particularly important for me to discuss modifications of performances together with the musicians. Therefore, I combined partially structured interviews with open conversations. The aim was to gain contacts in the sense of a “reflexive opportunity and an ongoing dialogue” (Titon 1997 p. 94), through which results might be attained cooperatively by all persons involved.

In the following, I will first introduce the repertoire of tambrin music with its subgenres and describe various contexts of performance. I will then return to my questions, considering some theoretical approaches and discussing forms of interaction as they differ and change, depending on contexts of performance and as they characterise the single subgenres. The term “interaction” will refer to the musical texture and also to the interplay of musicians and dancers or audiences which again has an impact on the musical texture.

[2] Repertoire

Reel and Jig

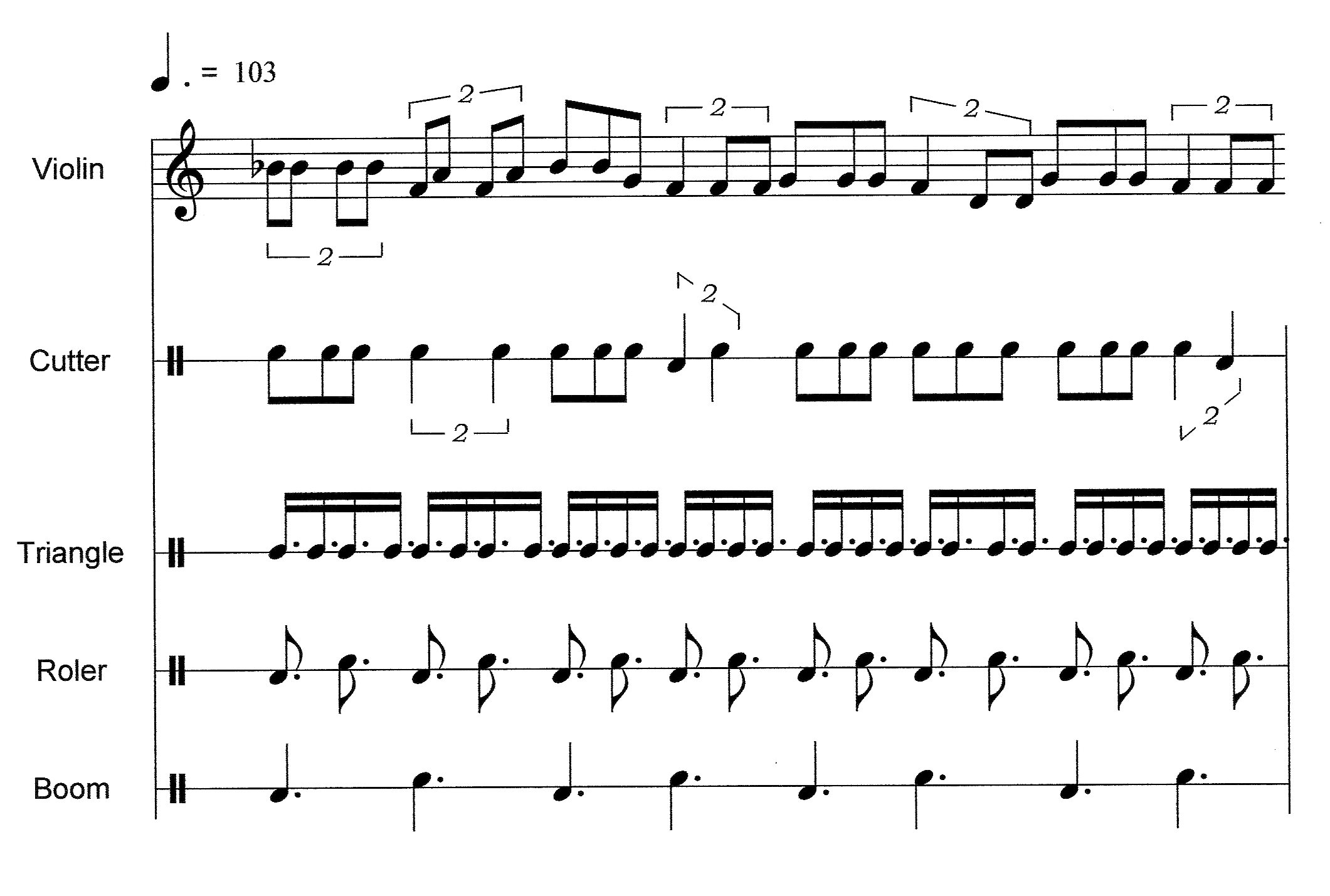

A tambrin band traditionally uses five instruments, a violin, a triangle, and three tambourines, which are tuned to different pitches by heating them at an open fire. The deepest tambourine is called “boom”, the middling “roller” and the highest “cutter”. The terms “roller” and “cutter” can also be used for the musicians playing these instruments.

Reels and jigs make up by far the largest part of the repertoire. Both are characterised by 3:2 cross-rhythms. Two of the tambourines – roller and boom – as well as the triangle mostly underlay the playing of the leading drum and the violin or harmonica with steady beats. Eight beats of the triangle go together with four beats of the roller and two beats of the boom. For the roller and boom open strokes are carried out with the thumb, muted strokes with the other fingers (whereby the fingertips briefly remain on the membrane). The tunes played on the violin or harmonica and the drum patterns of the cutter are characterised by constant changes between binary and ternary subdivisions of the beat marked by the boom. Frequently, the playing of the violin and cutter results in juxtapositions of duple and triple groupings (Ex. 1). The cutter varies the rhythm of the melodic lines or parts of them. Sometimes, however, the drum patterns turn out to be largely autonomous, especially in the recordings from 1995 (Ex. 2).

“Tuning” the tambrin, 2008. Photo: Andreas Meyer.

Although some younger drummers, particularly from the Professionals and Mount Cullane, vary their patterns less frequently, their playing also leads to 3:2 cross-rhythms. The drumming of the cutter in all four groups is characterised by various playing techniques. A high, open stroke is carried out with splayed fingers at the edge of the drum. Muted strokes are played rather in the middle with closed fingers. Fast sequences of beats are executed with single alternating fingers. In addition to these commonly practised techniques, there are various individual ways of playing. The drummer Prince Williams, for instance, who played for “The Rising Youth”, used the fingers of the hand that holds the drum not only to play a slight off beat inside the instrument (as it is common in many cultural areas) but also to change the pitch by pressing the membrane. Other tonal differentiations result from a different intensity of beats played with single fingers.

Ex. 1: Caterson Tambrin Band, Jig, 1995.*

* Here and in the following examples: for drummers’s open strokes the stems point up; for muted strokes the stems point down. For reels and jigs, triple figures are presented as regular, while quadruple figures and equidistant divisions in four, eight or 16 beats are shown with dotted notes. One has to keep in mind here that even-numbered groupings actually prove to be a more constant factor. This becomes clear not only in the parts of the triangle, roller and boom, but also by the movements of the dancers. Divisions into triple steps are only carried out when the dancers imitate the playing of the cutter, after which they always revert to an even beat. I write triple figures as regular notes only because the drum patterns of the cutter can be recorded more conclusively in that way.

Ex. 2: Caterson Tambrin Band, “Call Me Momma Gie Me” (reel), 1995.

The melodies, sometimes also sung by musicians and recipients, are often based on banter songs, which were once invented spontaneously. The violinist George Charles described this in an interview as follows:

As you give a reel dance […] you might not know that song tonight. But when you look at – you know – some female come with a big belly in the dance, […] you compose a song the same time. […] And you know the person, you call the person by the name, she belly a grow. That means she will have a baby in she belly (Interview 1995).

Charles’s statements correspond to descriptions by cultural anthropologist J. D. Elder who documented jigs and reels in his collection of “Folksongs from Tobago”:

Most jigs, like reels, are usually critical of social life in the village although some may be rather viciously satirical. Mostly, they make fun of queer behaviour and comment upon scandals about which people would not ordinarily venture to speak (Elder 1994 p. 79).

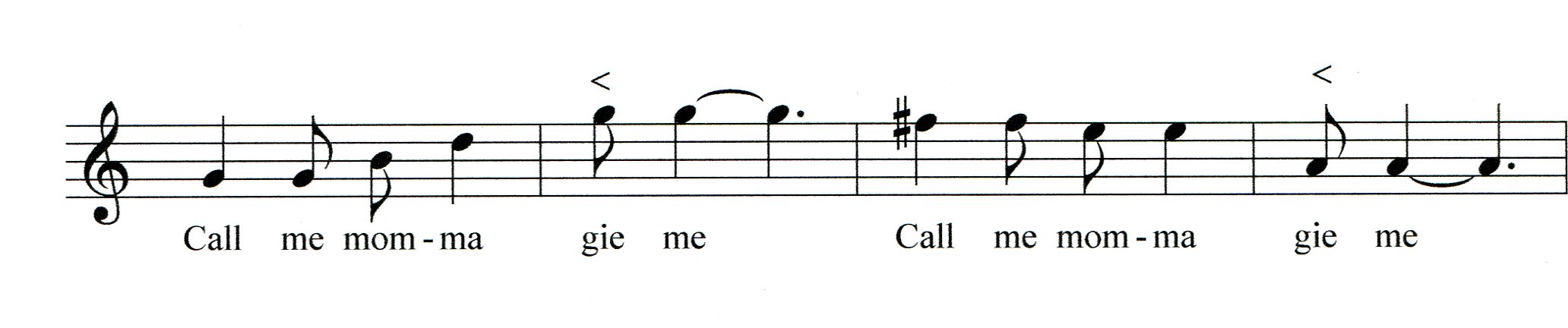

The spontaneous lyrical compositions prove to be rather simple. A typical example can be found in Elder’s collection, a jig entitled “Call Me Momma Gie Me” about a young man who finds himself in prison (Elder 1994 p. 80):

Call me momma gie me (Call my mummy for me)

Call me momma gie me

Call me momma gie me

Tell am me lack-up (Tell her I am locked up)

A ‘tation jail oh (At the station jail)[9]

Other lyrics refer to the religious meaning of tambrin music by singing of ancestral spirits and their environment. Furthermore, musicians use songs borrowed from other contexts, like Christian hymns arranged as jigs or reels.

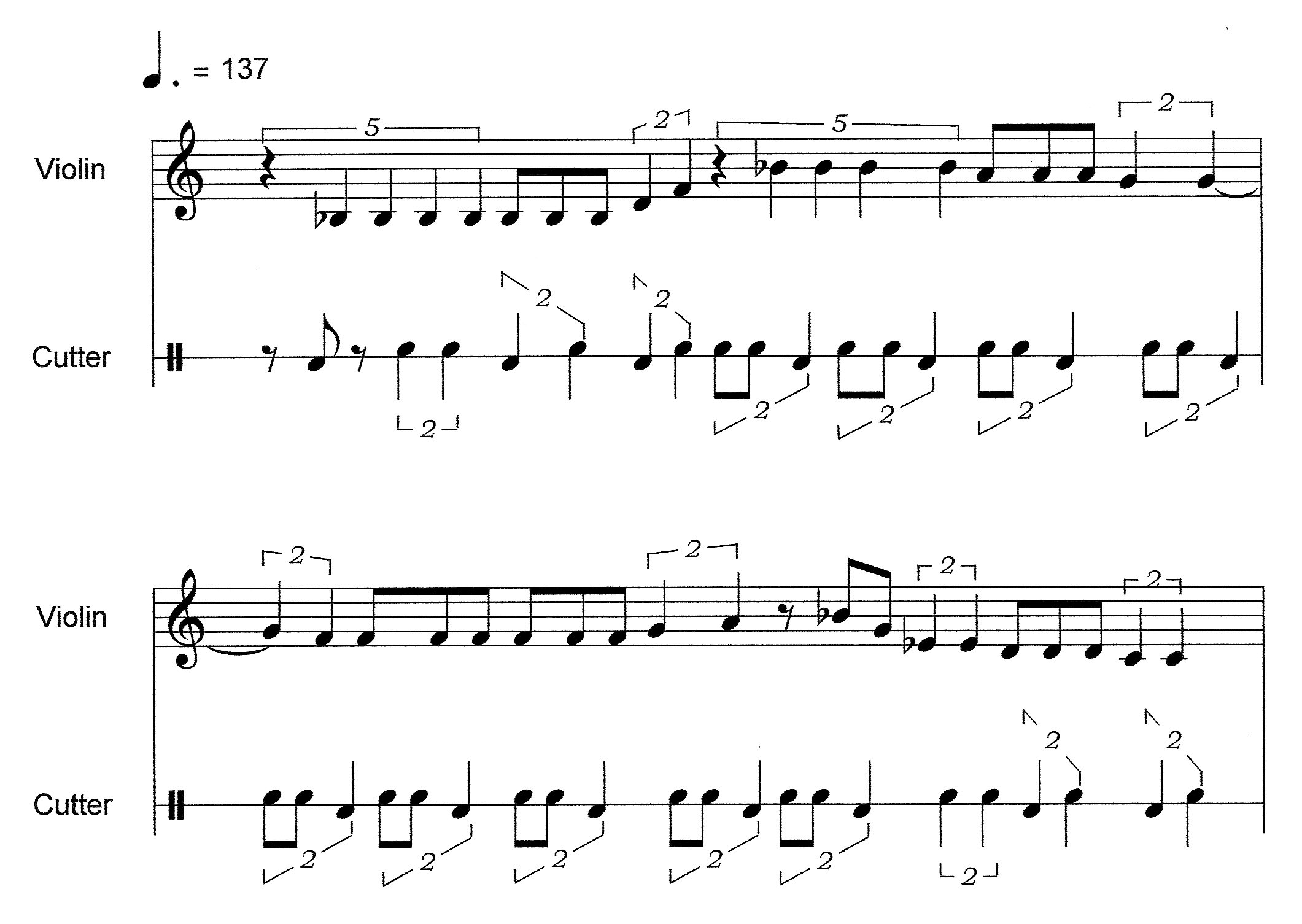

Many songs are based on call and response forms and diatonic scales. Violinists and harmonica players may interpret melodies quite freely and in an abbreviating manner. The recording of a jig called “What Bailey Do You” (again about a prison inmate) is one example of this practice. The song comprises two related parts. Both are based on call and response (Ex. 3). The instrumental version as performed by Gary Cooper, who played harmonica for The Rising Youth in 1995, is restricted to stringing together four rhythmically identical phrases which are repeated constantly (Ex. 4).

Ex. 3: “What Bailey Do You”, sung by Prince Williams and other members of The Rising Youth, 1995.

Ex. 4: “What Bailey Do You” (Jig), harmonica: Gary Cooper, 1995.

The jig is played more slowly than is the reel, but the respective ways of dancing provide a more distinctive difference. Both dances can be carried out solo or in pairs, whereby the partners dance alone or hold each other’s waist to perform circular movements. A regular subdivision of the beat marked by the boom, often done with shuffle steps or regular changes between heel and toe, is characteristic for the reel (Video 1). The jig is frequently danced with large sweeping steps taken on each second beat of the boom (Video 2). This is particularly typical for the female part and is often maintained as long as the dancers do not carry out the circular movements with their partners. Correspondingly, the musical phrases of the jig often encompass two beats of the boom, the first of which is accentuated by the melody. The songs are normally either assigned to the jig or the reel repertoire. However, due to free interpretation, individual melodies can be played as jigs and as reels, making the different musical structures of both dances especially clear. As seen above, J. D. Elder refers to the song “Call Me Momma Gie Me” as a jig. He writes it in 3/4 time. One bar apparently corresponds to two beats of the boom. For every other bar, the first beat is accentuated melodically (Ex. 5; Elder 1994 p. 80).

Ex. 5: “Call Me Momma Gie Me” (Jig) as written down by Elder (accents added)

The piece was assigned to the reel repertoire by the Catersons I met in 1995. The accentuation of beats, typical for the jig, was removed due to the melodic figuration of the violin when they performed it (Ex. 6, see Ex. 2).

Ex. 6: “Call Me Momma Gie Me” (Reel), violine: Rawl Titus from the Catersons, 1995.

Marches, Pasa, other Subgenres

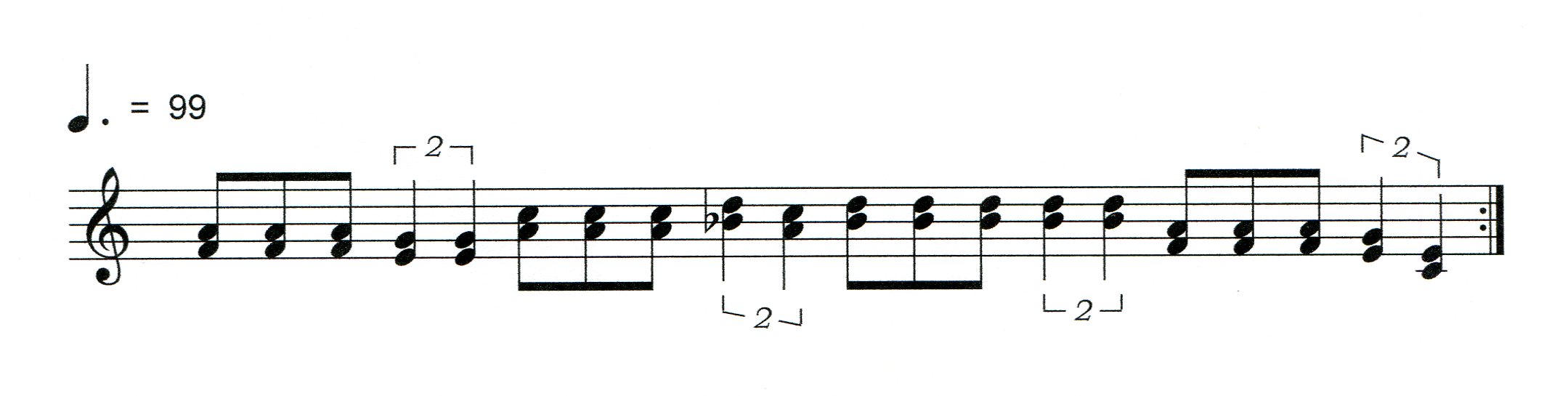

Some other dances beside reel and jig are integral parts of the tambrin repertoire. First are the marches, which are also connected with a song repertoire. The slow and solemn melodies can be traced back to European scales and are connected with a drum playing largely characterised by an even subdivision of a four beat meter (Ex. 7). Mitchel Smith, leader of the Mount Cullane Tambrin Band, termed this style of playing “soft music” (personal communication 2009).

Ex. 7: “Valentine” (march), Professional Cultural Group, 2009 (Video 3).

Another subgenre is called “pasa”. The term refers to the paseo or pasillo, a form of dance music which is known in various Latin American countries. It is frequently played in triple meter with multiple off-beat accentuations (cf. Riedel 1986 pp. 5–6). The paseo was adapted in Trinidad at the beginning of the 20th century, and there it merged with varieties of calypso (cf. Rohlehr 1990 p. 140). A pasa in Tobago is a calypso or another popular song in a quadruple meter, mostly from colonial times and connected with dances carried out very freely. It holds a kind of middle position within the repertoire of tambrin music. The 3:2 cross-rhythms are less frequent than for reel and jig. Compared to the marches, though, the interaction proves to be richer in rhythmic tensions. The melodies of the violin or harmonica are marked by the off-beat emphasis and anticipated notes typical of calypso music. They are imitated by the leading drummer in altered form (Ex. 8) or accompanied by him with regular subdivisions of the meter (Ex. 9). The melodic aspect is of greater importance for the pasa than for jig and reel because the audience more often sings along with the violin or harmonica, since the songs are generally well known. During a wedding in 2008, I could hear a number of these kinds of songs.

Ex. 8: Brown Skin Girl (pasa), Unity Folk Group, 2009.

Ex. 9: “Fire Brigade” (pasa), Mount Cullane Tambrin Band, 2009.

Some other dances, according to various musicians, are only played as stage presentations today. These include heel and toe polkas (in Tobago simply “heel and toe”), waltz-like dances called “castilian”, as well as quadrilles (in Togabo “cagedrill”), all of which are connected with a certain repertoire of tunes. A band can also be invited to accompany singing, for instance at a wake when hymns are chanted all night long (Mitchel Smith, personal communication 2009). Beyond that, the repertoire of a tambrin band is actually unlimited. Some older musicians stated that it has always been an all-round ensemble which, when it is engaged, must comply with the requests of individuals in the audience.

[3] Engagements

Tambrin music is traditionally played to entertain people but it is also connected with the belief in ancestral spirits and can cause trance and possession, as Krister Malm describes (see above). It plays a major role at so called “reel dances” held as healing ceremonies, which follow a ritual procedure. Family members and friends are invited, as are special healers if they cannot be found within the family.[10] In the beginning, the crowd marches from the patient’s house to the next bigger crossroads. There, the ancestors are invited with libations to take part in the ceremony. The tambrin band plays a march in the style described above. After that, the group returns to the house. Sometimes the people dance the whole night long. The musicians perform reels, jigs and sometimes a pasa. The healers fall into a trance, let the ancestral spirits enter into them, and thus they learn from the spirits how they can help. After that, treatments with herbs and baths begin, as the case requires. In this context, reports on spectacular cures of cripples and fatally ill persons circulate in Tobago (cf. Meyer 2000 p. 226; Meyer 2006 pp. 29–30). The possession by spirits is an elevating and at the same time painful process. My informant Sealy Edward, an insider who has a great deal of experience on how to deal with ancestral spirits and who was recommended to me by musicians as an expert on religious background, described it as follows:

The spirit takes you. […] The strength that you will get there, you are having strength that you could take four–five men and pitch them anyway you want to pitch them, no mind how big they are. Because when the spirit takes you, its double strength you get in. You understand what I’m talking? It gives you another power. And that power – nobody can hold you. […] But it’s a great, great experience for anybody. That spirit when it takes you when you beating the drums. When you play a certain music that spirit takes you, like a pasa, sometime like a jig, and it comes on you. And you got to know what you are doing. If you don’t know what you are doing, trouble takes you. […] Well it’s about a few years now, I coming and joined a small fete. I try to get away from it because it used to damage me. You know, when you are in this dance business, you have to take off your shoes and sometime your shirt and roll out the pans. Sometimes I get cut and I don’t know if I get cut until the other day. […] You don’t feel anything when you are in that spirit. So I used to get a lot of bumps and cuts and things. So I try to keep away from the tambrin music. A very dangerous thing! (Sealy Edward, interview 2008).

Beside reel dances, family celebrations, in particular weddings, were formerly the most important occasions to perform tambrin music. At weddings, ancestral spirits traditionally also play an important role. They are invited with libations to take already part at the celebrations the night before the wedding (Bachelors’ Night). A tambrin band plays and sometimes guests fall into trance and possession, which enables them to make predictions about the marriage. The musicians play again the following day. They accompany the guests on a procession from the church to the groom’s house with solemn marches. Brushback is danced, where the partners link arms with each other and move forward and sideways together. Later the musicians play to let the people enjoy the occasion. Here again spirit possession can occur, although, as Sealy Edward reports, rather unintentionally:

Most time in the wedding, you know, the beats and the spirit will take you there. But nobody want no obstruction on that day. So the fiddler and the tambriners will slow down the music so that the fellow could catch himself. Because if that happen, the spirit takes you and throw you on the table and mash up … the wedding. So when the spirit comes down on the dancer, most time the fiddler will stop the music and from the time the fiddler stop the music the tambrin will stop and ease up the situation there (Sealy Edward, interview 2008).[11]

Today the groups hardly ever play in the traditional surroundings, a fact that could be observed already on my first trip in 1995. A DJ with a “sound system” is normally hired for weddings. Traditional medicine has lost its relevance. Engagements to play are offered by hotels and restaurants. Further opportunities to perform come about at political events and above all folklore festivals.

The annual Tobago Heritage Festival is of particular importance here. It lasts for two or three weeks with central events in Scarborough, the capital of the island, and performances in single rural communities. The concept goes back to J.D. Elder, who initiated it in the 1980s as a member of the Tobago House of Assembly. The so-called “Folk Fiesta” holds a prominent position, as according to the programme from 2008, it is one of the “festival’s signature events”. Contests in different categories are organised on this occasion, including “Traditional Folk Song”, “African Song”, “Tobago Folk Dance”, “African Influenced Dance”, and “Speech Band”. Formerly there were also competitions of tambrin music, but recently, tambrin bands just supplement the programme together with other types of ensembles (especially drum groups) and accompany the speech bands, costumed dance groups who make voluble speeches. According to Mitchel Smith, the musicians play reels and other “native fast tunes” between the speeches (interview 2009). The combination of speech bands and tambrin music is quite old and can possibly be traced back to sugar harvest festivals in the 19th century (Hernandez 2004 p. 3). The decentralised rural activities focus on so-called “stage productions”, mostly burlesque theatre performances with cultural heritage themes. Meanwhile some of these productions have become annual key events, for instance the “Ole Time Tobago Wedding” in the village of Moriah. Step by step, a wedding and its traditional rituals are performed as a comedy. The tambrin band and its music are integrated dramaturgically. Sometimes the plot is interrupted and a dance group comes on stage to present choreographically arranged jigs, reels and other dances to the tambrin music. The groups also present themselves in this manner when they play for tourists. However, restaurant and hotel managers sometimes prefer to forgo dance performances to lower costs.

“Ole Time Tobago Wedding” in the Village of Moriah (with the Mount Cullane Tambrin Band),

Tobago Heritage Festival, 2008. Photo: Andreas Meyer.

[4] Some theoretical approaches

Transculturation, polymusicality

The research questions raised above correspond to theoretical reflections on cultural influences in the Caribbean and to manners of musical performances in different contexts more generally. Regarding the juxtaposition of European and African spheres, one has to keep in mind that Caribbean music has always been characterised by creole blends. In the 1940s, the Cuban anthropologist Fernando Ortíz thus introduced the term “transculturation”. According to him, cultural forms of expression in Cuba (and therefore arguably in other Caribbean areas) were strongly and disproportionately marked by the contributions of many different ethnic groups, but within a transcultural process which “involves the loss or uprooting of a previous culture” (Ortíz 1995 p. 102). Bronislaw Malinowski, who wrote an introduction to Ortíz’s work, substantiated these claims. Transculturation, he states, stands for contacts in consequence of which

a new reality emerges, transformed and complex, a reality that is not a mechanical agglomeration of traits, nor even a mosaic, but a new phenomenon, original and independent (Malinowski 1995 p. lix).

The concept of transculturation, repeatedly utilized by ethnomusicologists (e.g. Kartomi 1981; Kubik 1994; Warden 2007), can be read as a rejection of approaches that attempt to trace Caribbean music back to European and African models. In times of “small media technologies” and “accelerated transnational movements of people, capital, commodities, and information” (Stokes 2004 pp. 47–8) such approaches seem to be even more obsolete. However, one must remember that regional classifications are actually carried out by musicians and recipients. Protagonists commonly associate Caribbean genres or some of their features with the African and European “heritage” (musicians in Tobago I talked to did it again and again). Musical attributes accompanying such classifications are often easy to find, especially in the field of music considered traditional. On the whole, they hardly concern specific features of single African or European genres but rather “general principles” (Manuel 1996 p. 6) of musical form, intonation, forms of interaction, etc. A wide variety of musical genres and styles based on these heterogeneous principles is known in the Caribbean. In this context Kenneth Bilby has introduced the term “polymusicality” to describe the ability to move “across a stylistic continuum” or an “African-European musical spectrum”[12] (Bilby 1985:203), the potential components of which he describes by means of an example:

A tiny island such as Carriacou (seven and a half miles long by three and a half miles wide, with a population of roughly six thousand) can lay claim to as many as ten or fifteen distinct “types” of folk music, ranging from predominately African-derived traditions such as the big drum dance on the one hand to British balladry on the other. In many of the larger islands, internal regional variation creates an even more complex situation (Bilby 1985 p. 202).

Preservation, participatory and presentational performance

The presentation of tambrin music on stage, the dominant performance mode in recent times, complies with the kinds of efforts to preserve cultural heritage that are very popular in many Caribbean countries. Music and other cultural resources are re-evaluated as media to construct or imagine communality (cf. Anderson 1991 pp. 5–6; Hobsbawm 1983 pp. 104–5). State-run cultural centres, music festivals and folklore competitions are established and they present on stage forms of expressions considered traditional. The preservation of culture also has an economic value, above all in connection with the tourism industry, particularly important for most of the Caribbean islands. Folklore groups present local “traditions” in hotels, restaurants or to welcome guests at harbours and airports. They satisfy the tourists’s need for exotic impressions and help them to experience their holiday destination as something clearly different from their usual environment (cf. Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1998 pp. 152–3). Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett has introduced the term “heritage” for the phenomenon of cultural preservation apparently found world wide:

Heritage, for sake of my argument, is the transvaluation of the obsolete, the mistaken, the outmoded, the dead, and the defunct. Heritage is created through a process of exhibition (as knowledge, as performance, as museum display). Exhibition endows heritage thus conceived with second life (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1995 p. 369).

One has to keep in mind here that heritage activities do not only refer to the past. They rather become new social events by themselves (cf. Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1995 p. 370; see also Shapiro 2004). “Transvaluation” always implies significant innovations. For the domain of music, changes are frequently due to the transition from “participatory” to “presentational performance”, as Thomas Turino calls it (Turino 2008 pp. 23-65). A passive audience has different expectations from the music than does a crowd who wants to dance. Turino refers to examples from various regions, noting that the transition is often accompanied by a change from dense textures (in which “different parts overlap and merge so they cannot be distinguished clearly”) to transparent textures (“music in which each instrumental or vocal part that is sounding simultaneously can be heard clearly and distinctly”) (Turino 2008 pp. 44–5). In addition, a pressure to succeed and thereby the wish to reach an audience as big as possible may arise. Performances may then be characterised by “new and strong effects that could raise attention” (Ronström 1996 p. 60; see also Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1998 p. 73; Livingston 1999 p. 80). Presentations of single musical pieces become “fast and clear-cut messages” (Ronström 1996 p. 62) and thus they are normally much shorter than they might be, say, at a dance night. Conversely, a purist attitude can develop in an effort to achieve “authenticity” and to satisfy the “call for ‘realness’” (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1995 p. 375; see also Baumann 1996 pp. 80–1; Livingston 1999 p. 74).

[5] Forms of interaction: change and stability

For jigs and reels a direct interaction between the dancers and the leading drummers is especially characteristic when the tambrin bands perform at weddings and other traditional ceremonies. This was repeatedly emphasised by musicians I talked to and is seemingly an important factor for trance and possession. At a Bachelor Night in 2008, I observed a female dancer moving towards the cutter and virtuosically imitating the fast and complex drum patterns (and the drummer possibly also imitated some of the dance steps).[13] This communicative factor provides the opportunity for the drummers to vary sequences of beats and to create patterns which move away from the ostinato melodies of the violin or harmonica. The spontaneous interaction of drummers and dancers is replaced by choreography when performed on stage. Moreover, the shortness of the performances thwarts the development of the drum part. Single pieces hardly take more than three minutes. Furthermore, a striving for musical perfection is important for playing on stage, at least for some of the protagonists. Musicians from groups where the drummers often beat their patterns in a rather restrained way (Mount Cullane and Professionals) particularly stressed at interviews and in conversations that accuracy of ensemble playing, exact timing and clarity of sound were essential for them. This corresponds to the characteristics Thomas Turino described as the transparent texture typical of presentational performances (see above). Striving for accuracy seemingly leads to moderated, hardly varying drum parts. The resulting dominance of the violin or harmonica is accompanied by changes of melodic features. The part of the violin at stage performances is often not restricted to repetition of a few melody lines. Sequences are varied or connected into medleys and sometimes musicians even change between violin and harmonica in a show to create diversified melody parts. Thus one could conclude that – along with the rising importance of stage programmes – a change in the hierarchy of instruments within the ensembles has taken place. This is supported by statements from the violinist Seon Forde. Asked about particular stylistic features of his group he said:

In like all music it had to have a leader or like the vocalist, them sing the verse. In our music the violin becomes the vocalist singing the words and song. And the tambourine, the roller, boomer, cutter and the steel that is the rhythm, percussion, rhythm to keep tempo and keep the timing while the violin do the singing (interview 2008).

Seon Forde (Professional Cultural Group), 2009. Photo: Andreas Meyer.

Such remarks contradict views of musicians in 1995 who considered the tambourine the dominant instrument. They can be understood as a plea for more European or Euro-American forms of musical interaction. One has to keep in mind here, though, that the older musicians in 1995 already performed predominately on stage in front of an audience, and thus one may ask why musical changes were hardly relevant for them. One possible explanation could be that the older men had internalized the traditional ways of interacting and thus preserved them on stage. However, it should be noted here that even the contemporary groups still perform at family celebrations and religious events, if rarely. As mentioned above, in 2008 I had the opportunity to hear tambrin music at a harvest festival of a Spiritual Baptist Church congregation. Spirit possession and living with the ancestors play essential parts in religious life for Spiritual Baptists. In this case, the music was played by the Professionals with Seon Forde on the violin. They started around 9 pm and performed until the next morning, playing nearly exclusively jigs and reels, occasionally interrupted by the singing of Christian hymns. A large number of parishioners fell into trance while dancing. The violin as a “singing” and “leading” instrument was out of the question. Its part was restricted to simple repetitions. The part of the cutter, on the other hand, which was taken on by various musicians, came to the fore with multifarious interactions between drummers and dancers.

The musicians have apparently internalized different forms of playing for reel and jig according to different contexts. Nevertheless, boundaries between presentational and participatory performances can be unstable, cross over and be marked off differently by the protagonists (cf. Bau Graves 2004 pp. 68–9). On a recording session in 2009, again with the Professionals, the ensemble playing largely resembled the programme of a stage presentation, and the musicians performed together with a dance group (Video 2). In 2005, I had recorded the band playing with a children’s dance group in a similar way (Video 1). Then, the children carried out dance figures following instructions and the percussionists played in a rather restrained manner. In 2009, the dancers and musicians were of the same age; from the beginning, a joy of playing developed with manifold communication between all of them.[14] Straightaway, the drumming came into the fore by the creation of many patterns, a variety of sounds and a steadily increasing tempo. I talked about the differences of the two recording sessions with Elsima Forde, the leader of the ensemble. In an interview, she stated:

If you playing for a show, you have all the instruments’ sound coordinated. But if you playing for your own purpose, you find out we are playing in a different way. Like a reel dance, the music will sound different if you playing for a show. So you have the real hot music Saturday. You have the real thing Saturday. What you had the last time maybe was that for a show like Heritage, you play in one to coordinate the music right. Everybody have a tempo they have to go. But you see yesterday (Saturday) everybody was playing out of self. So you get the substance of the music Saturday. (Interview 2009)

Elsima Forde not only establishes a link between playing styles and performance events here, but also differentiates between “real” and staged forms. That dichotomy may lead to reason about purist attitudes and thus about striving for authenticity in stage presentations. Some efforts in this regard concern the violin and its playing. First of all, the use of the harmonica as an alternative is considered inauthentic by many protagonists, an opinion which is evidently shared by organisers. The violinist Laurence Crook, for instance, reports that he is sometimes engaged by the group Mount Cullane because promoters explicitly want a violin (interview 2005). As mentioned above, Laurence Crook has taken classical violin lessons and therefore learned to place the instrument under the chin while playing. Nonetheless, he instead presses the instrument against his upper arm or the upper chest (as the older musicians did) and has to move the instrument to play the different strings, which rather seems to hinder a fluid style of playing but hardly affects the sound. Changes of playing by Unity’s violinist Gary Cooper prove to be more serious. After having had lessons, he developed his own technique with frequent usage of double stops. The comparison of his recordings from 2005 and 2009 reveals large differences. The clear sound has again given way to a rather scratchy, hazy style. On the other hand, Cooper’s playing is not at all restricted to simple repetitions as with the older violinists. He also tries to entertain his audience with melodic variety and surprising turns. Apart from the way of handling the violin, purism plays seemingly a minor part for staged performances. According to my experiences, musicians and recipients rarely question changes of forms of musical interaction.[15]

Another look at the entire repertoire of tambrin music with its various subgenres might help to understand, how these changes are perceived by the protagonists. In contrast to reel and jig, 3:2 cross-rhythms and short ostinato melodies are not characteristic for marches and waltzes, and their rather even drumming mostly appears as an accompaniment of the melodies. There is also little room for rhythmic complexity when the groups play to accompany hymn singing. Apparently different principles have always been relevant for musical interaction in tambrin music, whereby the pasa holds a kind of middle position. Kenneth Bilby’s model of “polymusicality” with its “African-European spectrum” related to a “stylistic continuum” (see above) can be applied here. The entire spectrum is important for tambrin music both past and present. In times of cultural preservation and the presentation of traditional music on stage, the pendulum swings towards the European-like direction, which does not, however, question the continuum as a whole, at least so far. This spectrum model can explain to some extent outcomes from conversations I held with musicians of various generations where I presented recordings of reels and jigs from 1995 and 2005 and asked whether they perceived any differences.[16] Apart from Seon Forde, who understood his own usual style of playing the violin as different from the styles heard on the older recordings, only one of the older tambourine players criticised the lack of diversity in a young drummer’s rhythms, saying: “He is not very experienced.” All of the other respondents found no real differences between the recordings. Although during other talks some protagonists emphasised links between ways of playing and performance contexts, different forms of musical interaction were here widely considered neither significant nor anything specifically new.[17]

[6] Conclusion

When performed in traditional contexts, jig and reel as subgenres of tambrin music are highly characterised by the interaction between drummers and dancers. The part of the leading drummer is accordingly complex, whereas the simple, repetitive melodies seem to have an accompanying function. The combined playing of the lead drummer and the violin or harmonica often results in 3:2 cross-rhythms. The establishing of stage performance in the contexts of cultural preservation and entertainment for tourists leads to a decreasing importance of spontaneous communication and a rather passive audience. New contexts foster transparent textures, more restrained drum parts and the dominance of melodic lines (while the typical rhythmic-metric tensions are retained). Thus, changed performance conditions lead to a new way of playing although other reasons for these innovations may be important too, for example a stronger orientation towards international mainstream music. The new way of performing jig and reel cannot be considered a fundamental change because musicians are able to switch gradually between the different forms of interaction according to occasion and circumstance, and because all musicians’s performances are not affected equally. Moreover, it is not a new concept of interaction, but has always been part of the stylistic continuum. This becomes clear when considering the repertoire as a whole.

References

Anderson, Benedict 1991: Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, London: Verso. First published in 1983.

Bilby, Kenneth 1985: “The Caribbean as a Musical Region”, in: Sidney Wilfred Mintz and Sally Price (eds): Caribbean Contours, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press: pp. 181–218.

Baumann, Max Peter 1996: Folk Music Revival: Concepts between Regression and Emancipation, in: The world of music, vol. 38, no. 3, pp: 71–86.

Cartagena, Juan 2004: “When Bomba Becomes The National Music of the Puerto Rico Nation”, in: Centro Journal, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 14–35. Available at: http://redalyc.uaemex.mx/pdf/377/37716103.pdf .

Davis, Martha Ellen 1994: “‘Bi-Musicality’ in the Cultural Configurations of the Caribbean”, in: Black Music Research Studies, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 145–60.

Elder, J.D. 1994: Folksongs from Tobago, London: Kamak House.

Graves, James Bau 2005: Cultural Democracy: The Arts,Community and the Public Purpose, Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Guilbault, Jocelyne 1985: “A St. Lucian Kwadril Evening”, in: Latin American Music Review, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 31–57.

Hernandez, Edward 2004: “The Role of the Heritage Festival in Society”, unpublished paper, The Centre for Creative and Festival Arts; Carnival Studies Colloquium 26.2.2004–27.2.2004.

Herskovits, Melville J. 1943: Pesquisas ethnologicas na Bahia, Bahia: Museu do Estado.

Herskovits, Melville J. 1956: Man and his Works: The Science of Cultural Anthropology, New York: Knopf.

Hobsbawm, Eric 1983: “Introduction: Inventing Traditions”, in: Eric Hobsbawm & Terence Ranger (eds), The Invention of Tradition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kartomi, Margaret J. 1981: “The Processes and Results of Musical Culture Contact: A Discussion of Terminology and Concepts", in: Ethnomusicology, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 227–49.

Kirschenblatt Gimlett, Barbara 1995: “Theorizing Heritage”, in: Ethnomusicology, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 367–81

Kirshenblatt-Gimlett, Barbara 1998: Destination Culture: Tourism, Museums, and Heritage, Berkeley et al.: University of California Press.

Kubik, Gerhard 1994: “Ethnicity, Cultural Identity, and the Psychology of Culture Contact”, in: Gerard H. Béhague (ed.), Music and Black Ethnicity: The Caribbean and South America, Miami: University of Miami North-South Center Press, pp. 17-46.

Livingston, Tamara E. 1999: “Music Revivals: Towards a General Theory”, in: Ethnomusicology, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 66–85.

Malinowski, Bronislaw 1995: Introduction, in: Ortíz (1995), pp. lvii-lxix.

Manuel, Peter 1996: “Introduction: The Caribbean Crucible”, in: Peter Manuel with Kenneth Bilby and Michael Largey, Caribbean Currents: Caribbean Music from Rumba to Reggae, Philadelphia: Temple University Press, pp. 1–16.

Manuel, Peter 2009: “Introduction: Contradance and Quadrille Culture in the Caribbean”, in: Peter Manuel (ed.), Creolizing Contradance in the Caribbean, Philadelphia: Temple University Press, pp. 1–50.

Meyer, Andreas 2000: “‘Morning Neighbour Mornin’’ (reel), played by the Ensemble ‘The Rising Youth’”, in: Artur Simon und Ulrich Wegner (eds), Music! The Berlin Phongramm-Archiv 1900–2000, CD booklet: Museum Collection Berlin/Wergo, pp. 242–46.

Meyer, Andreas 2006: “The Older Folks Used to Fiddle Around the Notes. Playing the Violin for Tambrin Bands in Tobago (West Indies)”, in: Studia Instrumentorum Popularis XVI = Folklore Studies, vol. 32, pp. 26–35.

Ortíz, Fernando 1995: Cuban Counterpoint: Tobacco and Sugar, Durham & London: Duke. First published in 1940 (in Spanish).

Philipp, Margot Lieth 1990: Die Musikkultur der Jungferninseln. Studien zu ihrer Entwicklung und zu Resultaten von Akkulturationsprozessen, Ludwigsburg: Philipp.

Riedel, Johannes 1986: “The Ecuadorean Pasillo: ‘Música Popular’, ‘Música Nacional’, or ‘Música Folklórica?’”, Latin American Music Review, vol. 7, no.1, pp. 1–25.

Rohlehr, Gordon 1990: Calypso and Society in Pre-Independence Trinidad, Port of Spain. Published by the author.

Ronström, Owe with contributions by Krister Malm and Dan Lundberg 2001: “Concerts and Festivals: Performances of Folk Music in Sweden”, in: The world of music, vol. 43, no. 2 + 3, pp. 49–64.

Rouget, Gilbert 1985: Music and Trance: A Theory of the Relations between Music and Possession, Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Titon, Jeff Todd 1997: “Knowing Fieldwork”, in: Gregory Barz and Timothy J. Cooley, Shadows in the Field: New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology, New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 87–100.

Turino, Thomas 2008: Music as Social Life: The Politics of Participation, Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Shapiro, Roberta 2004: “Qu’est-ce que ‘l’artification’”, in:

http://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/docs/00/06/71/36/PDF/Artific.pdf. Accessed : 30/8/10.

Schechner, Richard 2003: Performance Studies: An Introduction, London and New York: Routledge.

Stokes, Martin 2004: “Music and the Global Order”, in: Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 33, pp. 48–72.

Warden, Nolan 2007: Afro-Cuban Traditional Music and Transculturation: The Emergence of Cajon pa los muertos. Saarbrücken: VDI. Available at: http://www.nolanwarden.com/Warden-CajonPaLosMuertos.pdf (under the title Cajón Pa' Los Muertos, Transculturation and Emergent Tradition in Afro-Cuban Ritual Drumming and Song. MA Thesis, Tufts University 2006, accessed 26/08/2010).

Notes

[1] An Island Carnival. Music of the West Indies. Explorer Nonesuch Series 72091. Recorded 1969–1971 in the Lesser Antilles. Licensed from Caprice Records, The National Institute for Concerts, Stockholm, Sweden CAP 2004:1–2. Re-edited as CD: Electra Nonesuch, 7559-72091-2, 1991.

[2] According to a peer reviewer of this article, the music was actually recorded in Trinidad.

[3] Since the beginning of the 19th century Tobago was in British hands until it became independent in 1962 to form a nation state with the sister island Trinidad. The population until today is predominately African Caribbean.

[4] “tambrin” = abbreviation common in Tobago for “tambourine” (spoken and in writing).

[5] The name “Mount Cullane' refers to the three neighbouring villages of Mount Thomas, Culloden und Golden Lane.

[6] The Band Unity emerged from The Rising Youth at the end of the 1990s. It was founded by the families of two sisters, Ursula Cooper and Esilma Forde. Later the Forde Family separated from the group to form the Professionals. The Mount Cullane Band is led by Mitchel Smith who performs with his children and grandchildren. He is the cousin of Esilma Forde and Ursula Cooper. Esilma Forde’s sons, who together with their father James Forde form the core of the Professionals, used to belong to the dance group of Mount Cullane when they were children. The Coopers, Fordes and Smiths as well as most of the members of their bands live in one of the villages mentioned above. The no longer existing band The Catersons was, as the name suggests, also a group run by a family. Located at the east coast in 1995, they also stem from the northwestern uplands. The late Arthur Cooper, who played cutter for the Pembroke Performers in 1995 was a cousin of James Forde, the violinist George Charles an uncle of Gary Cooper. Gary Cooper’s father was also a prominent violinist. The members of Sweet Fingers – elderly men who mainly live in the village of Plymouth except for violin player Laurence Crook – do not really fit into this picture.

[7] The research trips were funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation).

[8] The video recordings from 1995, 2005, 2008, and 2009 are kept at the Berlin Phonogramm Archiv.

[9] Spelling adopted from J.D. Elder. Transcription into standard English added by the author.

[10] If not indicated otherwise, the descriptions here and below are based on personal communication with various older musicians whose statements concur.

[11] Apparently psychological processes are at work here as were already described by Melville Herskovits in the 1940s. The music functions as an “agreed-upon signal” which might be responded to by the dancers with a learned “conditioned reflex” (Herkovits 1943 p. 25, cited in Rouget 1985 p. 177).

[12] A somewhat different approach is pursued by Martha Elen Davis. According to her, Caribbean musicians do not move across a stylistic continuum but often shift between “two general musical idioms, each of which may be manifested by various genres” (Davis 1994 p. 158, fn 6).

[13] Similar forms of interaction can also be found in other Caribbean dance music genres, as for example the Puerto Rican Bomba (Cartagena 2004 p. 17).

[14] Obviously mechanisms called “flow” by American performance studies scholars showed themselves to be important here, a “feeling of losing oneself in the action so that all awareness of anything other than performing the action disappears” (Schechner 2002 p. 88).

[15] In our conversations only one drummer, Clint Cooper from the Unity Folk Group, once criticised the fact, that the violin is pushed into the foreground when it is amplified electrically on stage.

[16] Following protagonists were questioned: Lloyd Turner (Catersons), Prince Williams (The Rising Youth, Sweet Fingers), Mitchel Smith, Percil Smith (Mount Cullane), Elsima Forde, James Forde, Seon Forde (Professionals), Ursula Cooper, Gary Cooper, Clint Cooper (The Rising Youth, Unity).

[17] I would like to thank Sidney Hutchinson, Marietta König, Ulrich Morgenstern, Rainer Polak, Birgit Wilkinson, and Brigitte Wündsch for support and helpful comments.

Back to ref. 1 (Video 1) Back to ref. 2

Back to ref 1 (Video 2) Back to ref 2