Natures and Cultures

The Landscape in Peterson-Berger’s “Symfonia lapponica”

Annika Lindskog

[1] Introduction

Wilhelm Peterson-Berger (1867–1942) is laid to rest next to the picturesque church of Frösön, which sits on the highest point of the island, overlooking lake Storsjön and the mountains of Jämtland in all directions. A little below the church, Peterson-Berger built his Sommarhagen in 1913–14, his own Troldhaugen or Ainola, using it first as summer residence and later as a permanent relocation from Stockholm. Sommarhagen sits on a slope down from the church, nestling amongst the trees, with windows and porches gazing across open fields, water and mountains, at once both a part of the landscape, and a place from which to view it. It engages even further in a dialogue with the landscape through its form. In disjunction with the traditional architecture of the area, Sommarhagen shies away from the local building style which aimed to isolate the indoors and its occupants from the surrounding outdoors, and instead opens up towards the landscape (the associations of the name itself, “Summer Meadow”, sharply contrasting with the solid, functional style more commonly employed). Instead of trying to keep the forest at arm-length, Sommarhagen seems to exist, embedded amongst its trees, as much in the landscape as of it. It hereby realises several juxtaposition, or “tensions” in Wylie’s terms (Wylie 2007 pp. 1–11), that we can see as being at the core of our approach to and understanding of landscapes. Sommarhagen, built with natural materials and local techniques, remains very much of its local landscape, yet represents a created product within that landscape. As it blends in with its surroundings, it could be regarded as part of the landscape, yet its windows and verandas simultaneously provide a place from which to observe the same landscape. And further, although the building is a mixture of various styles and techniques, it has a particularly close relationship with the early mountain lodges of the Swedish and Norwegian mountains that were beginning to appear at start of the twentieth century, and which are emblematic of an aspiration to get “closer to nature” by walking in its remote and uninhabited areas. Peterson-Berger, a keen mountain rambler himself who spent most of his student summers with a rucksack and some friends on seven-week hikes through various regions of northern Sweden, was scathing towards anything too bombastic in these, and tended to praise the simpler, more primitive buildings – those that, in his view, related to their surroundings rather than imposed on them.[1]

Sommarhagen, then, gives us a starting point for investigating how Peterson-Berger understood the landscapes that surrounded him, as well as his own role in creating and re-creating them. Furthermore, Sommarhagen can be placed in the tradition of artistic residences at the turn of the nineteenth/twentieth century which linked personal style to artistic expression, and must therefore also be understood as “a very personal and deliberate monument” not just over the owner but also over “his creative output” (Karlsson 2006 p. 73). Across the road from the house are the slopes down to the water where Arnljot, the historical hero from the Viking past of Peterson-Berger’s second opera (often referred to as his most “national”[2]) would appear first in 1908 and and from 1935 in subsequent performances up until our days (performed as “talskådespel”, spoken drama, with accompanying music).[3] In 1914, the summer Peterson-Berger first took up residence, he wrote his last set of Frösöblomster (“Frösö Flowers”), a collection of piano pieces which are one of the most enduring legacies of Peterson-Berger in the Swedish musical consciousness, and where some of the titles function as direct evocations of the surroundings of Sommarhagen. The building thus seems less an isolated occurrence and more a representative expression of a complex relationship between composer, landscape and creative output, all inextricably linked, and simultaneously both a result of and conditioned by their interconnectedness. As Sommarhagen, much of Peterson-Berger’s music exist within a relationship with the landscape, a landscape at times inspirational and influential, at others apprehended and modified, some times framed, at others evoked, at yet others felt. But, again as with Sommarhagen, this relationship is neither fixed nor one-dimensional, and needs rather to be understood as a continuous dialogue between the music, the landscape, and our understanding of it.

A landscape, Cosgrove and Daniels stated in 1988, is a “cultural image” (1988 p. 1). It may appear tangible, a solid matter, even “natural”, yet our understanding of it, our approach towards it and perspective of it, is elusive and continually evolving. Nor are these perspectives solely individually contingent, the “cultural” part of the image is a collective response. The way we view nature can be said to be a result of “attitudes and ideas”, ethical, moral, societal and scientific ones, “which people have embraced and are embracing” (Sörlin 1991 p. 26), akin to a continuing collective framing and re-framing of the landscape. The emotional potential of any landscape must be understood then as a process which is influenced by changing historical conditions (Löfgren 1999 p. 40), it being “our shaping perception that makes the difference between raw matter and landscape” (Schama 1995 p. 10).

In other words, without our interpretation of it, “landscape” would not exist. It is through our approach to it we define it, through our rhetoric, artistic or otherwise, that we create its role and its meaning. Landscapes could be understood then, as some human geographers would argue, as a “milieu of meaningful cultural practices and values” (Wylie 2007 p. 5), and our approach to them are contingent on our “ways of seeing” them, or the “thought-patterns”[4] that surround them. Landscape, or rather our perspective of and response to any given landscape, needs therefore to be understood not as anything fixed (temporally, materially or spatially), but as a continuously evolving approach both in terms of view and viewer, a place for mediation between values and expressions. One such mediation occurs when landscapes form part of cultural practices and become “painted, intoned [or] flavoured”[5] (Löfgren 1999 p. 41) according to these patterns and gazes. It is in this context of a mediated and evolving landscape and its place and part in a cultural society that the relationship between Peterson-Berger’s Third Symphony, published as Same-ätnam. Lappland (“Land of the Sami. Lapland”) but conceived of in its conception as a “Symfonia lapponica”, and the landscape it revolves around becomes interesting to consider.

There is also a memorial stone for Peterson-Berger, which stands at his birthplace in Ullånger, Västerbotten. Erected and unveiled in 1976, it contains a collection of inscriptions: Peterson-Berger’s date of birth, his signature, a copy of a bronze relief of the composer, and two lines from a poem by Bo Bergman, originally dedicated to Peterson-Berger on his 70th birthday. The stone itself, of a height of 4 meters, had been found in the surrounding mountains and with considerable effort transported from its natural habitat to the lawn in front of the house where Peterson-Berger was born.[6] Aspects of both cultivation and domination of landscape is evident in this act, but it also has reverse implications. By selecting for the memorial of Peterson-Berger a stone lifted straight from the landscape, uncultured, raw, and “authentic” – borrowed, if you like, for the occasion and imprinted with socio-cultural sign-posts, but with nothing of its essential form changed, balancing instead as a juxtaposition between “nature” and “culture” – the stone functions less as a back-drop to the cultural memorisation of Peterson-Berger and more as an integral part of the act of memorial. “Nature” here is only partially tamed – transported, re-situated and imprinted it retains the landscape itself at its core, as Peterson-Berger’s demonstrable connection with that landscape, when re-located into his music, is equally conditioned by its essential form.

There is however a further dimension at play here. The poem that provides the quotation on the stone concerns itself with what the core identity of “Sweden” might be, and lists the thunder in the forest from an approaching mountain storm, the long day at the harrow and the stories from ancient times – in other words the natural resources, the tilling of the land, and the locally conditioned historical connections. If we are ever parted with this homeland, it is suggested, it is through music that our longing will be evoked, and the poem here presents “Swedishness” as a composite achieved through the trinity of nature, history, and art.

Stephen Daniels has suggested that we think of national identities as shaped by “legends and landscapes” – by stories of glorious or harmonious pasts and great deeds, situated in mythological and beautified scenery. The deliberate “activation” of a historical continuum in a given geographical area gives substance to the imagined community of the Nation. Landscapes can here become “national icons”, as they “provide visible shape” and “picture the nation”. As poets, painters and other artists narrate this landscape, they also help to depict and shape the national identity, together with historians, geographers, architects and others (Daniels 1993 p. 5).

In Bergman’s poem, Peterson-Berger’s music, as Daniels suggests, is presented as a catalyst for the national, mediated through the landscape, and localised in its connection to the remote and only partially inhabited region of Jämtland:

You are Swedishness itself when you make your mental fight into music

and the spiritual chorus of the expanses reverberate around Frösön[7]

Peterson-Berger worked in a period when both nature – by which I here delineate the natural landscape and its resources – and landscape – here an ideological narration of nature – were of primary focus for the “new” Sweden that was starting to take shape after the break-up of the union with Norway had permanently deprived Sweden of wider east–west territories, and after the onset of industrialisation, modernisation and urbanisation demanded new perspectives for the country now dominated by a north–south polarising.[8] Bergman’s poem, although written three decades into this process, nonetheless seems to understand Peterson-Berger and his art as at the cross-roads between nature and nation.

There are examples of this “inter-connectedness” of nation and nature to be found in other musical contexts. Daniel Grimley, here discussing Grieg, sets it out as “the definition of nationhood in terms of landscape” and “the formation of a national culture through its association with the national environment” (2006 p. 2), and argues that “representations of landscape in Grieg’s music are inextricably bound to broader cultural formations of Norwegian identity” (p. 221). That it is also verifiable that it was Grieg’s “life’s dream to be able to render the North’s nature in sound” (p. 222), only makes the dis-entanglement process more complicated.

Equally so with Edward Elgar in England. The quintessential Englishness of Elgar’s music is to a large extent bound up with an idea of Elgar as the “ideal Englishman”. This ideal, in turn, is to quite a significant extent derived from Elgar’s affinity with the landscape, in his case the area of Malvern and the river Severn. Elgar was a “self-made” composer, who had unconventionally learnt his trade locally, outside the formal training provided by the Royal Academy in London and the leading composer-teachers of the day, Hubert Parry and Charles Villiers Stanford. He himself talked much about the personal importance the landscape had to him, and often suggested that he drew direct compositional inspiration from it. This allowed a perpetuation of the myth of Elgar as a “natural” composer, by which “audiences [can] hear Elgar himself in his symphonies and through this are taken back to his own associations with the history, language and countryside of England” (Trend 1985 p. 17).[9]

The music of Elgar has then come to be heard through the filter of our perceived understanding of Elgar’s relationship with the landscape, as well as through our own affinities with that or any landscape, much like Grieg is heard through a complex interaction of rhetoric around landscape and national identity. Grimley (2010) parallels Nielsen and Elgar for the role “sensibilities of place” seem to play in writing on their music and how their implication in “localist patterns of thought […] underlines the pervasiveness of such myths of origin” (2010 pp. 17–18). To this day, Elgar is often depicted in conjunction with images of the landscape of Malvern, not seldom standing by his bicycle, a symbol for a personal and explorative relationship with the landscape.[10] It further also exemplifies an often prevailing attitude which approaches “landscape” as a given concept, and which frequently fails to engage with how this landscape relates to any music that it is understood to connect to.

We therefore need to start by trying to understand the processes by which such affiliations are created and perpetuated, and the extent to which music exists within and is conditioned by its social, cultural, and political real-context. Jeremy Crump wrote back in 1986 regarding the Englishness of Elgar that

the survival of music and its establishment in the repertoire is not simply a function of the inherent qualities of the piece, but an interaction of the music with contingent circumstances which are not all generated within the musical world. There are crucial periods at which music criticism and the music business serve to mediate wider cultural and political forces. […] Such links between societal forces and changes in musical tastes remain little explored. (Crump 1986 p. 185)

These links have lately been gathering more interest, but in his 1997 review of the most recent history of Swedish music (Musiken i Sverige), Gunnar Eriksson still reaches a similar, perhaps even more widely applicable, conclusion. He argues that “almost every form of music displays functions which, among other things, mirror, express, and shape the conceptions of its audience”. Recognising that extracting and analysing these functions may not be straight-forward, he suggests that this should not make us think they are not there: “trends within the music can very well reflect a spirit of an age without the connections being at once obvious” (1997 p. 102).[11] But Eriksson, along with Crump, finds that this aspect of music still often remains insufficiently explored.

The attitudes to and ideas of Nature that permeated Swedish society from the last part of the nineteenth and into the early twentieth century were central for the collective identity that developed at the same time. What the rest of this article will do is try to examine how Peterson-Berger’s Third Symphony took part in the dominating discourse that surrounded the Swedish landscape in general and the attitudes to the northern parts, Lapland, in particular.

[2] Love and lust for landscape

At the end of the nineteenth century, Sweden was still underdeveloped. Industrialisation would come relatively late, and widespread poverty, among other factors, drove large parts of the population to emigration. A parliamentary enquiry into the causes of the population-loss was set up in 1907, after figures had reached a new peak around the turn of the century (35 000 left in 1903 alone, with figures remaining high until WW1). The final report from the enquiry, a full 21 volumes published in 1913, may have had limited impact for external reasons, but among the social, economic, and educational reforms it suggested, it is interesting to note the promotion of ideological patriotism: it was above all necessary to make the people, and in particular the young, see their country as “a land of the future”, worthy of both emotional and practical investment (Barton 1994 p. 165).

It is to this aim the Swedish landscape became central and the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century saw a shift in perception of landscape and nature. At the same time as the extent and significance of the natural resources emerged, “Nature” as something with an aesthetic, moral, and philosophical value became one of the focal points and a locus for a collective, unifying, and ultimately national, identity.[12] The interpretation of “Sweden” needed definition and re-definition following the changes that industrialisation, urbanisation, modernisation, and the loss of Norway brought on, and the close identification with the physical landscape that emerged as an increasingly central part of the common national imagination manifested itself in various ways. These included a heightened interest in the natural environment expressed for example through the re-awakened interest in and promotion of Linnaeus,[13] as well as a growth in popular fascination for natural science. Another facet was the increasing pre-occupation with caring for the landscape, and a discourse for protecting and preserving the natural environment grew together with the establishment of various institutes aiming to ensure proper handling of the natural resources Sweden had throughout the nineteenth century gradually discovered that it was blessed with.

Examples of this include the first law for protection of the natural environment, Sweden’s first national parks, [14] and the establishment of Naturskyddsföreningen (The Society for Protection of Nature, NSF), all in 1909, while the first “fridlysning” of a species (proclaiming it inviolable by law) came the year after. The first paragraph of the constitution of NSF states explicitly that it exists to awaken and nurture a love for nature,[15] and exemplifies well the inter-relationship that existed between landscape as physical and as ideological matter.[16] The focus on the individual’s responsibility for the landscape and the desirability of developing a personal relationship with it inherent in NSF’s approach, can be seen even more clearly in Svenska turistföreningen (The Swedish Tourist Organisation, STF).

Started in 1885 by a group of students and their teachers at Uppsala University, and growing rapidly in both numbers and support,[17] STF appears to be at the heart of the forces that wished to promote both an intellectual and a physical contact with the Swedish nature. Their motto was from the start “Känn ditt land” (“Know your country”) – today rephrased into “Upptäck Sverige” (“Discover Sweden”) – and its statures from 1891 include the aim that they “spread knowledge of the country and its people” (STF 1891 p. 156). At this time, their activities focused almost exclusively on the mountain regions in the north, and among other things they produced maps, marked out walking routes, built huts for hikers to stay in, put rowing boats in the largest lakes, lobbied for reduced fares for young people and published geographical posters for the schools. In this way it gathered and disseminated information, as well as clearing – in a very physical manner – paths into the landscape. It is worth noting, however, that what they are doing is not simply enabling, but also to a degree rather forcefully “encouraging”, an open attempt at fostering a common attitude towards nature and our relationship with the landscape. Peterson-Berger had close links with this organisation, not just as a keen hiker himself, but also professionally through the articles and walking diaries he wrote for their magazine.[18] This magazine, STF found reason to state at its 25th anniversary in 1910, “has been one of the most important educational tools for the Swedish people”.[19]

Another “educational tool” was the re-narrating of Sweden and its landscape as a collective project that took place in Nils Holgersson, the school book commissioned (again by a parliamentary body) from Sweden’s most successful novelist at the time, Selma Lagerlöf. The journey of the shrunken boy on the back of migrating geese, written in the years directly after the dissolution of the union with Norway and their journey effectively covering every geographical area of what was left of Sweden, does not only make the country geographically distinct, but fills the contours with content – the landscape, its people, its stories, and its traditions. It is however also a moral tale: from the shrinking of the boy as a punishment for cruelty to animals, to the various tales and actions the boy encounters on the way, Nils Holgersson is a Bildungsroman with a strong emphasis on the value of the landscape and the desired attitude in our relationship with it and its inhabitants.[20]

Although each part of Sweden is treated on its own individual merits, one landscape comes across as of particularly significance. As the flock of geese together with the boy reach the beginning of the northernmost parts, Nils remembers a story he once heard from an old “Lapp-man”. The story was of another group of birds, living in southern Sweden, which had heard of the plentiful northern areas and was considering moving up there. They sent out an advance party to have a better look and report back. As the area to be investigated was so vast, the advance party split up and covered different parts, with the result that when they returned, they told vastly different stories. As they start to get cross with each other for not being able to agree on one description, the older birds intercede:

Do not quarrel. We understand from what you say that up there are to be found both a large mountain region and a large lake district and a vast forest area and a vast agrarian area and a large archipelago. That is more than we had expected. It is more than most kingdoms can pride themselves on having within their borders.[21] (Lagerlöf 1981 p. 468)

In the old man’s story, the older birds deem this prime country and they move northwards without delay. This appreciation of the region, as told through Lagerlöf’s story, echoes the particular position these northern parts of the country held in contemporary society. In various contexts referred to as “Norrland”, “Lappland”, “fjällen” or “fjällmarkerna”,[22] they were not only the stuff of poetic prose, or simply fulfilling the role as exotic (domestic) wilderness, but they also contained most of the natural resources on which Sweden was relying for its anticipated and aspirational modernisation: the iron-ore, water power, forests and pulp-industry found in northern Sweden were central to the on-going industrial development and resulting potential prosperity.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, Norrland, with its natural resources, under-populated areas, and promises of great riches for those who knew how to extract them, was therefore often regarded, and referred to, as “Sweden’s America”.[23] The emigration to Norrland from the rest of Sweden contributed to a population increase of about 85 000–100 000 per decade between 1870 and 1920, and during the period of industrialisation the population of Norrland doubled, with the greatest increase in the northernmost parts.[24] Norrland/Lapland clearly represented the future hopes, not only of individuals, but of the country as a whole, the “kingdom” to Lagerlöf above, to Sweden as a nation. The origin, foundation, and resources for these hopes lay in the actual landscape, its variety, its richness, and its vastness.

Lapland, then, held many of the keys for the aspirational future for Sweden, and a folio volume from 1908, dedicated to essays on and illustrations of its landscape, history, and industries, aptly entitled Lappland, det stora framtidslandet, mirrors well both the pseudo-scientific interest in the region and its incorporation in the national sphere. Virtually all essays take as their central point the physical characteristics of the landscape, and thus underline the perceived on-going exchange between nature and culture in the region. Particularly illuminating are the contributions by one of the editors, Frederick Svenonius. Svenonius, a geologist with a specific interest in Lapland and its glaciers,[25] and a founding member of STF, provides both the first and the final essay, and thus neatly frames the issues surrounding this land of the future. His concluding remarks concern Lapland as a tourist destination, but preferably one for domestic travel: the experience of which capable of enhancing the population as a whole and thereby enriching the nation, and in his conclusion he begs for travel- and accommodation discounts for Sweden’s young on the grounds that

[t]he profit for the nation will be larger than the millions the hotel and railway owners take from [other] rich national and international tourists several times over. The mountains foster a Spartan youth, and that is exactly what old Sweden needs.[26] (Svenonius 1908 p. 281; original emphasis)

But in his opening essay, as he sets out to give an overview (literally, from a balloon) over “lappmarkerna” and arrives at the newly named town of Kiruna, he cannot help but compare with an earlier journey, when all was “empty and tranquil”, and displays great ambivalence towards the developments the (recent) railway might bring:

Will that curious string of iron, which has been wound along the southern shore [of lake Torne] and even through the mountains, bring to our beloved Lapland and its people joy or sorrow? That is the question ...[27] (Svenonius 1908 p. 15)

On the one hand, Svenonius argues here for the Lapland mountains as something containing a specific moral value, of immense importance even beyond their commercial and industrial exploitation, almost a kind of “national training ground”; on the other he remains uneasy about the physical inroads into the landscape that are necessary if its riches and benefits are to be fully explored and utilised.

Svenonius’s anxious gazing at the railway between Kiruna and Narvik is an expression of the inherent impossibility he and others sensed of finding a resolution between the desire to keep Lapland as an unspoilt, natural commodity – representing the pure, ancient, grandiose Sweden and an embodiment of the sentiments found for example in the national anthem (“you ancient, you free, you mountainous north”) – and the unavoidable exploitation of the same landscape if the rapidly emerging “modern” Sweden would be able to prosper. This, then, is a landscape surrounded by conflict, at the core of contemporary debates on nature and nation, and it is this conflict and these debates Peterson-Berger’s Third Symphony engages with.

In the folio volume is also a painting by Folke Hoving of a solitary Sami in the midst of a dramatically rendered Lapland landscape (Fig. 1). To Peterson-Berger (he reviewed the volume for Dagens Nyheter) the reproduced painting was the “most eminent of the whole material”. It is entitled Sameätnam. Lappland, the same name Peterson-Berger would eventually give his symphony, and is the first illustration the reader encounters (between pages 4 and 5). Through its name it is made to represent the area in its entirety (all other have local or activity specific titles). It is also the only illustration to include a Sami (the others depict empty landscapes). Some 40 years earlier, C.A. Pettersson’s work (1866) on Lapland’s “nature and people” had seen numerous drawings that included Sami people, normally at work or in other in every-day situations. But by 1908 the only Sami included is sitting still, hunched, turned away from us.

Its placement and role among the other texts and illustrations make this painting pivotal for the whole volume, a point of reference for the other material, and one which reveals a myriad of contemporary disjunctions between a culturally conditioned and ideologically (and aesthetically) imbued “Lappland” and the geographically defined area of Lapland. Hoving’s painting is a feast of colours, at once both dramatic and peaceful, dark and light, intimidating and warm, close by and distant. The painting also includes all the natural riches of the north of Sweden in the water, the forest and the rock, as well as hinting at its vastness by the contours of distant mountains in the background.

It is then pertinent that Peterson-Berger should have taken the name for his Third Symphony directly from this painting. In his review, he describes the painting with artistic fervour:

[…] where the daylight of midnight burn with purply-blue, golden-green and fiery red fleeting nuances over mountains and wilderness and gaze soulfully at its reflection in a clear, dreaming lake between darkened forested shores, while in the foreground a young Sami sits with his back to the viewer, as if mourning in the face of all this melancholy and brightly sparkling beauty.[28]

Fig. 1: Sameätnam. Lappland. Painting by Folke Hoving,

as it appears in Frederick Svenonius (ed.) 1908.

The internal relationship between this painting and the symphony suggested in the identical titles is further underlined both when Peterson-Berger refers to the painting as direct inspiration for the symphony’s third movement (1917), and in his extended programmatic descriptions where the third movement is accompanied by a narrative re-working of the earlier review description:

The midnight sun, hidden behind torn skies, sprays glowing strips of colour over heaven and earth. High up on a slope in the foreground a youth of the Sami people sits and gazes over a wondrous landscape, a wide mountain valley, where a long, crystal clear lake detachedly repeats the coloured dreams of the sky and the clouds and the closing mountain wall’s blood-red summits and towers, facing the depths.[29] (Peterson-Berger 1918)

Hoving’s painting, as it appears in Lappland, det stora framtidslandet, is more than a physical representation, and functions at least in part as an interpretation of the conflicting approaches that the discourses surrounding this landscape were wrestling with. Just as Hoving’s painting reveals something fundamental about its contemporary context’s relationship with Lapland, its landscape and its inhabitants, so it is possible to find in the Third Symphony an engagement with the same landscape and the same conflicts.

[3] A “Symfonia lapponica”

Peterson-Berger’s “Symfonia lapponica”, composed some time between 1913 and 1917,[30] was first performed in Stockholm by the orchestra of the Royal Swedish Opera in December 1917, and then by the Stockholm Concert Society in March 1918. The Lapland connection was strengthened by the five Sami songs, or “joijks”[31] that Peterson-Berger incorporated in its musical material, and both performances were also preceded by commentaries published in Dagens Nyheter, whose regular music critic Peterson-Berger was. In these, he gives each movement a sub-heading and a brief introduction (1917), later expanding on these and providing a paragraph of “narrative” for each movement (1918). Both the sub-titles and the extended texts were used inconsistently, and neither made it to the published score (1922), but the four motivic headings have, together with the overall title, nonetheless tended to be included in any programme or description of the symphony since.

Although not often heard in the orchestra halls, the Third Symphony is still widely regarded as one of Peterson-Berger’s most successful large-scale compositions and has attracted some scholarly attention over the years, from the first reviews in 1917 and early analyses in 1937 to several more recent ones.[32] Two aspects return consistently in most of these. In the early analyses in particular, and in shorter summaries, there is a tendency to let the programmatic titles dictate a largely descriptive hearing of a standardised and generalised evocation of landscape, mostly without any extensive attempt at defining wherein the music this landscape can be found, or engaging with how the music and the landscape relate. The more recent discussions tend on the other hand to focus on the “foreign” material, the incorporation of the five joijks leading primarily to discussions of form,[33] provenance, and their significance as a “folk” element, in some cases to the exclusion of any programmatic dimension.

In some later analyses attempts at combining both these aspects have been made. Arvidsson (1998) touches on the different “types” of landscapes that might be found in the symphony, and hears the first and second movements as a subjective experience by a mountain walker (or subjective spectatorship, as Arvidsson implicitly seems to understand the whole symphony as a “view” of the landscape), while “only in the third movement” do “the feelings of the Sami youth take centre stage” (1998 p. 12). Arvidsson’s starting point, and main tenet, that the symphony cannot be understood as existing outside or independently of the rhetoric around its Sami connections (p. 9) and that the joiks helped create a wider cultural and societal awareness of the Sami music, has connections back to an earlier argument by Bohlin (1993) in which he suggests that it would be potentially rewarding to take a more ethnographic approach to the symphony, and extend the discussion of the joijks to the Sami as a whole. What role, he asks, did the Sami themselves have for Peterson-Berger’s symphonic work, and what role has the symphony played in developing our attitudes to the Sami and their culture? (Bohlin 1993 p.104) This is a highly relevant question, and one in which Bohlin identifies the potential embedded in expanding the range of ways in which we contextualise music, and regarding it as part of a socio-cultural fabric with both impulses and reverberation beyond the purely musical.

But I think it can be taken further than that. By reading this symphony primarily through its joijks – either as a musico-ethnological interest in folk-influences or as part of the on-going, post-colonial discussion of the political and cultural relationships with and attitudes to the Sami (or indeed a combination) – and disregarding other expressions, influences and contemporary contexts, we may miss other aspects of how the symphony reaches out to its context, contemporary and beyond. As suggested earlier, Peterson-Berger’s Same-ätnam is surrounded by a contemporary ideology that saw the landscape both as a national resource and a national treasure, and the northern parts as both of economic potential as well as of aesthetic, moral and mythological value. Behind both the commercial needs and the rhetoric around cultural heritage lie several layers of ideologies on art and aesthetics as well as on social and political actions, and Peterson-Berger and his contemporaries often wrestled with contradicting values, not seldom within themselves. And, as discussed, we can in Peterson-Berger find a deep personal relationship with the landscape, expressed not only in Sommarhagen, but also in his long summer hikes through the Jämtland mountains, his hiking diaries, and his expeditions with his cartographer brother, to take but a few examples. It is however also a professional relationship, as the landscape again and again provides focus, inspiration, and narrative for his compositions. Arguably, the Sami aspect might then be better understood as part of the content rather than the entire content, and as one facet of many of the Lapland that the symphony engages with.

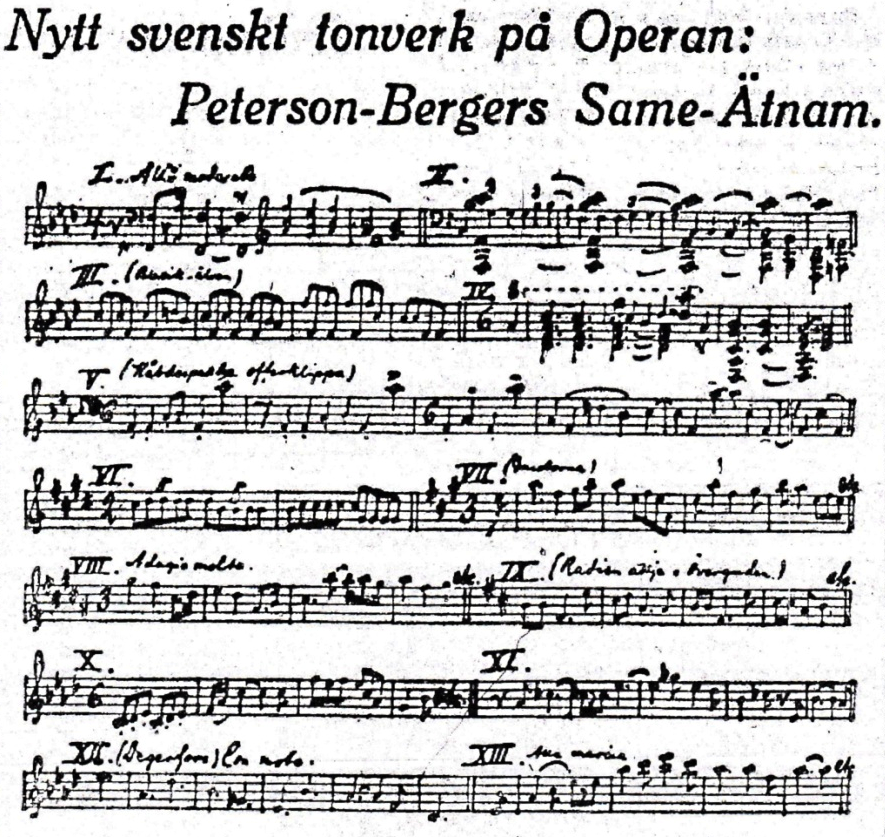

Peterson-Berger’s own introduction to the symphony, published in Dagens Nyheter three days before its first performance, suggests as much. Here Peterson-Berger writes out the 13 main musical themes from the symphony[34] (see Fig. 2). The five joijks are included, but surrounded by Peterson-Berger’s own themes, and although he refers to them by name and makes specific reference to them in the accompanying text, he credits them only with giving him his “first ideas” to the symphony.

Fig. 2: Peterson-Berger’s identification of the “main” themes, published in Dagens Nyheter, Sunday 9 December 1917, three days before the first performance.

Peterson-Berger – on other topics often both outspoken and prolific – publicly gave his attention to the music of the Sami on only one occasion, in an earlier article of 1913.[35] This was prompted by an exhibition of the National Museum’s latest acquisitions of ethnographic material in Stockholm in April 1913, and in which his friend the stationmaster, violin player, painter, Lapland-enthusiast and joijk-collector Karl Tirén partook with his collection of joijks from northern Sweden, including recordings.

The music of the Sami was not generally known at the time of Tirén’s exhibition, although it was not altogether unknown either. There had been a collection by Armas Launis published in Finland 1908 (to which Peterson-Berger refers), while earlier accounts of the Sami also often describe their music in general terms – the 1908 publication in Sweden on the Lapland region, for example, contains a section about their “ethnography, language and history”, by the Bishop of Luleå, Olof Berggren, in which he makes a brief reference to their songs, the only “entertainment they seem to amuse themselves with” (in Svenonius 1908 p. 80). Peterson-Berger acknowledges this earlier awareness, but still credits Tirén with “discovering” these songs, as they have only now met someone with the “warm-blooded temperament of the musician” and are for the first time being approached with an “infectious enthusiasm and admiration” (Peterson-Berger 1942 p. 217). Peterson-Berger also seems to find their geographical origin significant (Launis had documented Finnish and Russian areas), and even goes as far as suggesting that it is within the Swedish borders the oldest and most individual “lapp-music” is to be found (p. 220).

Peterson-Berger’s approach here suggest that his interest in these “lapp-songs” focus particularly on how they connect to the Swedish Lapland region and on their characteristics as musical and artistic expressions. He was as fascinated by the quirky melodies and their rhythmical structures as intrigued by their function as primarily descriptive imitations of natural features, places or people, and as he goes on to discuss the more technical aspects of the songs, he pays particular attention to the direct connection they appear to have with the objects they describe.

The relationship between the Sami songs and their “objects” need clarification. The songs are neither representations nor descriptions in a transferred sense, but a direct expression of both the characteristics of the object and the singer’s response to it: “in these songs the singer express[ed] through the melody his or her idea of the characteristics of a person or an object, as well as one owns feeling towards that, which one was singing about, or the memories that stir[red] at the remembering of a person or an object”. [36] The distinction is that you “joijk something” (from the verb “to juoi’gat”), rather than joijk about something (Ternhag 2005 p. 159). The joijk is therefore inherently reproductive in its physical form and expression, and linked via its single interpreter to its object directly, rather than through layers of imposed representation and interpretation.[37]

Peterson-Berger picks up on this relationship between the music and the object, and gives as an example the joijk to the “Sacrificial rock of Kåbdespakte”, the only musical material from this article that would later make it into the symphony. He explains the structural similarities between the joijk (theme V in Fig. 2) and the physical shape of the mountain rock: the first leap from the Bb to the major third and fourth represents a small hill, the second long leap to the D/8va (an interval of a tenth) the peak of the mountain. The joijks thus need to be understood as a specific expression of how the Sami view and relate to that which is being joiked about – here the landscape – as an interpretation of the object itself, and as an interaction between object and music.

Peterson-Berger further draws attention to the subjectivity in joijks. As these songs are expressions of an individual’s particular response to the be-sung object, they cannot be seen as a collective contingent: “this music is the Lapp’s way of artistically responding to reality, to mirror, high-light, idealise it and in this idealising express his or her personality” (p. 219). This challenges the interpretation of joijks as a collective representation of the Sami, and instead underlines a very individual response to and connection with the topics of joijks.

The Sami music is to Peterson-Berger then something individual and subjective. Yet, taken as a whole, they are also applicable as a local response to the Lapland landscape. Tirén called these songs “wilderness-poetry” and to Peterson-Berger they were “the finest extracts of the poetry of Lapland”, expressed in the indigenous language and filtered through in the music. Their language contained

musical images of the high mountains in northern Sweden: the howl of the wolf, the screech of the owl and the song of the cuckoo, the faint whispering from the river down in the valley and the clucking of the mountain stream outside the tent, frighteningly wild and alluringly mild, memories of a distant past and the battles of today […] all fused together (pp. 222–223).[38]

This, however, Peterson-Berger goes on to suggest, can only fully be heard and understood in the music by those who had heard this language spoken, shouted, or sung in the wilderness, and who had seen and experienced the nature of Lapland (my emphasis). Peterson-Berger here makes a correlation between the music and the landscape explicit, and the approach to the landscape into one of physicality, of experiencing the landscape as solid matter. But he also sees their combined functions as vessels for memories and legends, for emotional expression and poetic dramatization, and for an every-day battle-field for modern society. Before Peterson-Berger concludes this article, he underlines the value of this same landscape for Sweden, describing it as a “source of energy” for Swedish culture, and the introduction to “Lapp music” and the technical analyses of the joijks have now been taken up in a wider context – the cultural interaction between landscape and society. The conclusion itself contains the first reference to a “Symfonia lapponica” and the composer’s aspirations for it:

Those who understand how fortunate Sweden is to possess this great out-of-doors landscape, what a source of energy for Swedish culture that flows from coming into contact with such nature and with the nomad’s struggling, by necessity simple human life, they will also come to understand the value of this Lapp music, and perhaps is that tone-composer not far away who one day, out of sheer gratitude for all that Lapland has given him, will weave together the most beautiful of these songs to an artful and romantic “Symfonia Lapponica”.[39] (Wilhelm Peterson-Berger in Dagens Nyheter, 28 April, 1913)

If the joijks help strengthen the symphony’s relationship with Lapland, then the programmatic titles and descriptive texts provide further contextual material. That Peterson-Berger remained ambivalent towards these, and particularly towards the fuller descriptions he developed for the second performance (March 1918), ought not to see them dismissed from the context. Peterson-Berger was a habitually “programmatic” composer, in the sense that most of his compositions received inscriptions that pointed towards an intended character or relationship within or externally to the music. All his five symphonies, for example, have a more or less explicit programme embedded in their titles and subtitles: Banéret (The Banner) with its tapestry of scenes from the battlefield, and Sunnanfärd (A Journey South) with its extended narrative of the journey south and the longing for, and eventual return to, the home in the north, both preceded Same-ätnam, while Holmia (an elegy to Stockholm) and Solitudo (written at the end of the composer’s life) followed it.

James Hepokoski has argued that although programmes, or any “accompanying paratextual apparatus”, may complicate our analyses of any musical structures, once we have “been invited to draw connections” between the two, we are unable to dismiss the notion of them. Further, as they exist primarily in the reception, to try and discard them, as listeners, would be to fail to “play ball” and “break the rules of the game” (Hepokoski 2009 p. 232). Same-ätnam’s “paratextual apparatus”, even in its most limited form, refers the symphony to a context that we cannot “un-think”: what remains to decide is to what extent and in what way we allow contextual dimensions to inform our hearing of it.

Peterson-Berger’s ambivalence towards the programmes of Same-ätnam and failure to include them consistently might be understood more as ambivalence towards the extent to which the listening should be expressively guided – that he understood texts and programmes as having the ability to influence our hearing of musical textures is clear from his own writings (see for example his discussion on “Opera & erotik” in Dagens Nyheter 1935, in Peterson-Berger 1942). At the very least the programmatic comments, written either during or soon after the compositional process, might provide “hints” as to “which ideas and moods the compositions for him relate to” (Carlberg 1950 pp. 76–77), or reveal “ideas and moods that influenced him”, even if we are reluctant to see them as “a concrete description of the content” (Jacobsson 1998 p. 21).

That these early programmatic comments to Same-ätnam further appeared as newspaper items (thereby reaching a much wider audience than only those that attended the concerts) also makes them relevant for the role they play in the symphony’s contemporary context. Their dissemination into the public sphere also bears witness to a certain level of conviction in the composer regarding their central tenets. Further indication of this is perhaps the consistency with which the content of these texts developed. The 1918 version is an expansion of the 1917 article, which in turn echoes sentiments and phrasings that we can find already in the article from 1913 (and some from the review of 1908). The texts could then, in their various versions, be usefully employed for making space for additional motivic interpretations beyond the Sami material.

[4] Living Landscape

The titles of the four movements of the symphony – “Images of a distant past”, “Winter Evening”, “Summer Night”, and “Dreams of the Future”[40] – provide a framework which we can approach in different ways. The narrative aspects of the movements’ subtitles lend itself to a cyclical hearing, with the two outer movements representing the past and the future, while the inner movements are descriptions of the present, with one frame each for opposing seasonal images. Another occasionally employed approach is to hear the temporal divide as occurring between the third and the fourth movement: the first three evoking the idyllic, utopian understanding of Lapland, while the fourth shatters this idyll both metaphorically and musically (it is the least regarded of all the movements by later commentators in particular and is often heavily criticised for lacking in sophistication and musical coherence, if it is considered at all) as it tries to approach the threatening but seemingly unavoidable modernisation of Lapland that was underway. While both these approaches provide insight into the content of the symphony, I would like to suggest a third for the purpose of this analysis, one which sees the apex of the symphony as occurring within (rather than after) the above-mentioned third movement. Each of the movements could be understood as having an individual dialogue with the landscape, and it is the dialogue that is revealed in the third movement that is the most crucial one.

The landscape of the first movement is at first glance readily identified. It is the subject of a voyeuristic gaze, framed for us to view, a spectator even included in the 1918 text:

The vast wilderness lies melancholic and empty [of people], and dreams behind the green frontiers of the immense forests. The rivers sing their thousand-year old song, and high against the sky, blue, snow-capped mountain tops rise. If a wanderer reaches one of their peaks he sees sunny distant vistas stretching for miles in all directions: there the Blesik river glitters, there the Kåbdespakte sacrificial rock displays its many-pronged head.[41] (Extract; tempo marking Allegro moderato misterioso e fantastico.)

Peterson-Berger’s text emphasises the descriptive qualities of the landscape, containing an abundance of nouns, qualified by poetic adjectives, and it is possible to hear in the movement scenes, or even sacrificial feasts, “rushing past” (review in Dagens Nyheter, 12 Dec 1917). The movement contains five themes, as identified by Peterson-Berger, more than any of the subsequent ones, and suggestive perhaps of variety and richness, with the swift presentation of the first three of these in the opening of the movement (within 37 bars) further enhancing the impression of glimpses or snapshots of the shifting vistas. But in Peterson-Berger, the keen mountain walker and the artistic representer of landscapes, and the owner-builder of Sommarhagen with its dialogue with the surrounding landscape, landscape is never only a view, a tableau of frozen action to observe. Instead it is full of the tensions mentioned earlier, and perhaps better understood as a perpetually shifting duality, the tension between gaze and inhabitance continuously negotiated by varying perspectives.

The first movement, demarcated as images or pictures from the past, might nevertheless be understood to set out to depict and present a view. This “view” of the landscape was also being developed by contemporary artists, which sought to connect the characteristics of the landscape with a nationally expressive art:

Our art shall be like our nature! It will interpret our sui generis, our individuality, and our hearts’ dispositions and thereby use the colours and the shapes which are once and for all those of our country and our people. (Richard Bergh quoted in Frykman & Löfgren 1979 p. 57)[42]

The colours and the shapes understood to be “of the country and its people” are exemplified in Otto Hesselbom’s Vårt land (“Our Country”, 1902; Fig. 3): a vast, empty expanse, still and uninhabited, in muted, dreamy colours with a nostalgic shimmer, devoid of any activity, but with a dramatic light suggestive of its own emotional power and resources. Depicting an area of large lakes, dense forests and sparse population, “its seemingly boundless extent is viewed under the evocative conditions of a long summer twilight – a recurrent motif in Swedish art at the turn of the century. Contemplated through a lens of ineffable nostalgia … [it creates] an intensely emotional silent space where quasi-religious yearnings could be subsumed in the monumental and timeless grandeur of Swedish nature.” (Spencer-Longhurst 2009 p. 46)

Fig.3: Otto Hesselbom, Sommarnattsstämning. Studie (“Summer Night Mood. Study”), part study for

Vårt land (“Our Country”), 1902. © Foto: Nationalmuseum

Same-ätnam’s first movement could be heard to evoke similar imagery: its opening dotted rhythm up a minor third and back again, darkly orchestrated, answered by three-part, wistful-sounding, melancholically beautiful flutes; the second of Peterson-Berger’s themes (see Fig. 2:II) a figure of slow triplets over a pedal note, a cyclical and repetitious motion as a continuous echo of itself; the symphony’s opening minor third together with the second figure’s first interval of open fifths dominating the mood in the first 28 bars – all hinting at degrees of both vastness and emptiness in the landscape which find common ground with the painters’ expressions. This hearing has parallels also with Peterson-Berger’s later Norrbottenskantat (1921), in which Johan Norrby finds the choruses’ “pianissimos in a low register” and “empty fourths and fifths” in the third movement particularly effective as they seek to evoke the “chilly grandeur of the sleeping country” (Norrby 1937 p. 146). The Norrbotten Cantata was written for the 300 year anniversary of Luleå, but both the text by Albert Carlgren and Peterson-Berger’s setting let the cantata encompass all of Norrbotten, and Peterson-Berger identified the “evocations of wilderness” (vildmarksstämningar) in the poem as having “a certain kinship” with those “I myself have attempted to capture in Arnljot and Same-ätnam” (Peterson-Berger in Dagens Nyheter 31.7.1921; quoted in Fredbärj 1937 p. 249).

With the first of the joijk-based theme (Fig. 2:III), a shift in approach occurs however. It is a joijk for the river Blesik, faster-moving than any other phrase hitherto, and dominated by octaves and open fifths. By orchestrating it with harp and the higher registers of the piano (for whose inclusions on the symphonic platform Peterson-Berger was sometimes criticised) Peterson-Berger achieves a characterisation of the music that further enhances the joijk’s inherent quality as “being” its object and a physical imitation of the sparkling, clear-watered rivers that tumble with such multitude from the mountain-sides. Although the treatment of this joijk, and later that for Kåbdespakte, could be argued to function simply as “word-painting”, it is as “embodiments” of the natural landscape they have greater value. Here our visual viewpoint is being invaded by the physicality of the landscape, and through these joijks in particular, the symphony starts to suggest that its engagement with the landscape goes beyond that of merely depicting framed vistas.

For us as listeners, this attempt at making us experience the landscape, rather than simply view it, requires more of a sensory response, and as the first movement slowly peters out with short repetitions of the river theme, ending quietly back in F minor, it leaves us straddling the observer/inhabitant divide. This ambivalence ends, however, as the second movement’s opening bars throw us straight into a driving motion of a simple, but again cyclical, and in its repeated semi-quavers intense, theme passed around the orchestra. The “journeying” motion is steadied by consistent emphasis on the first and third beats in the bars, while a “walking figure” develops with the alternating tonic and dominant in the bass. All around this there are shrieks and clashes and howls and it is not difficult to hear in this Peterson-Berger’s “journey with an akkja and reindeer during a bitingly cold but clear winter night, across empty vistas with howling wolfs and shrieking snow” (Peterson-Berger 1918). The accompanying text is full of active, engaging, and highly evocative verbs: the bells tinkle, the snow squeaks, squeals, and bellows, the wolves howl, the sparks from the fire whirl and dance – and they are all rendered in the music: the “chaos” of the opening scene has high, fast quintuplets in flutes and oboes, sforzandi French horns and trombones in clashing chords, short, sharp slaps in harp and strings, semi-quaver glissandi in the piano, and tambourine, crash-cymbals and timpani in the percussion. There are also small, but continuous shifts in the orchestration and small rhythmical variations of the first theme as the movement develops, further heightening the sense of movement and unsettledness.

The destination for this journey is, according to the text, a Sami camp where a fire and warm rest awaits and it seems plausible that the joijk incorporated here functions as a representative for this camp. It is clear already from the 1917 comments that Peterson-Berger thought the tune was called “The Sparks”, though it seems this may have been a misapprehension.[43] The jumpy little tune (see Fig. 2:VII) could well be heard as imitative of sparks from a fire however, and with the 1918 narrative it becomes a double-representative of the Sami camp towards which we are travelling, and which is being glimpsed throughout the second movement. When the journey ends, it does so by a last round of “sparks” followed by quiet fractions of the sleigh-theme, and the movement draws to a halt (or so it seems) on a bright C# major chord.

Peterson-Berger refers to the second movement as a “kind of scherzo” (1917), and although this practice was not uncommon to him, here it is particularly crucial that the scherzo occurs ahead of the third movement. In this second movement we meet the landscape as something to experience, to travel through – we are being placed in the “akkja” itself, carried forward by the “sleigh-theme”, surrounded by, Peterson-Berger suggests, the remote, wild Lapland winter night, and with that our perspective has shifted from observation to participation, from a distanced objectification of the landscape to immersion in its actual nature and physicality. The gaze, this movement maintains, is not enough for comprehending this landscape, it will only render the spectator remote, neither in the landscape, nor related to it. Without the physical experience of being in the landscape, as Peterson-Berger underlined it in his discussion of the Sami music, we can not hope to understand either the landscape or the cultures it contains.

This distinction and constantly negotiated duality between an observed landscape and one of participation; between an objectified gaze and a subjective, and personal, experience; between what we see and what is, is what crumbles as we go into the third movement. Although it takes as its starting point a visual interpretation of landscape (in the form of Hoving’s painting), the approach here seems to be neither a “way of seeing” nor an attempt at subjective experience. Rather, it comes closer to what is sometimes called “embodiment” of landscape:

[D]ivested of assumptions regarding observation, distance and spectatorship, the term landscape ceases to define a way of seeing […] and instead becomes potentially expressive of being-in-the-world itself: landscape as a milieu of engagement and involvement. Landscape as “lifeworld”, as a world to live in, not a scene to view (Wylie 2007 p. 149).[44]

Despite offering itself to us in recognisable terms as “view”, Hoving’s painting, as already suggested, seems to contain several perspectives of the landscape and our relationship with it. Our view here is interrupted by the figure in the painting – we are no longer able to consider the landscape a matter of our own subjectivity, instead our every interpretation is mediated by the person inhabiting it. As we gaze at it, our interaction with the landscape becomes confused with that of the internal spectator. This spectator, however, is not himself looking at the landscape, nor engaging with it in any kind of activity as he sits with his head down and shoulders hunched. Thus confronted with the impossibility of both spectatorship and experience, landscape as “a world to live in” becomes a viable alternative approach. This world is one of beauty and majesticness, richness and multitude, but also conflicts and unresolvable tensions not between nature and culture but within both nature and culture. It is this “world” we find in Same-ätnam’s third movement.

The movement is built on two themes, Peterson-Berger’s own first theme and a joijk (Fig. 2:VIII & IX). The opening phrase of the first theme is a downward figure, stepping down by thirds (g#, e, c#), before reaching up above its starting point, not once, but repeatedly throughout the phrase, as if trying to counteract the mournful downward motions by ever higher starting points. What we hear in this phrase is open to interpretation, but most seem to agree on a “melancholic beauty” being embedded in its expression. The solitary first violins are joined by the other sections part by part as a canon of the first theme develops, culminating in an intense, harmonised “appassionata” rendition in full orchestra that seems to just, but only just, let the “beauty” dominate over the “mourning” Peterson-Berger saw in Hoving’s painting. It is about to fold into a resolved, perhaps even peaceful ending, when the joijk enters and brings the recently achieved major tonality back into a more sorrowful key of B minor.

The joijk seems to have a curios relationship with the theme that introduces the second act of Arnljot (Fig. 4a), commonly referred to as the first (of two) “Wilderness theme” (Vildmarkstemat). Although the melodic figure is reversed, they share tonality, rhythmic pattern and melodic intervals (Fig. 4b). Tillman has argued comprehensively for understanding the musical themes in Arnljot as “leitmotifs”, that is, as being tied to a particular character and in their usage commenting on their actions or characteristics (Tillman 2006). He identifies the “wilderness”-theme as a musical introduction to the nature of Jämtland but goes on to suggest that this is not the theme’s only function: it doubles up as a motif for Vaino, the Sami girl that plays an important role in Arnljot’s journey through the wilderness. As Arnljot and Vaino meet for the last time, the theme can be heard at various points throughout the passage, and it accompanies her as she bids us and Arnljot farewell (vocal score, pp. 247–48):

Vaino: “Here is my home… my soul one with the light of the wide expanses and the eternal song of the rivers / the dusk of the forest and the bird voice, the lichen’s flower and the sparkle of the spring / when you think of wilderness and solitude, Arnljot, then you remember me.”

Arnljot: “Yes, you I will remember.”[45]

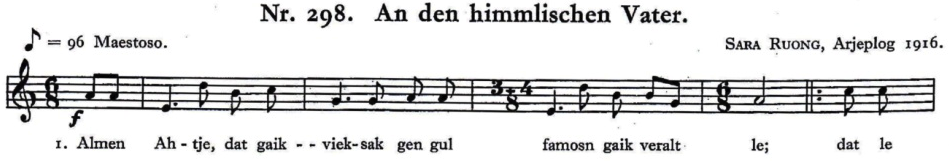

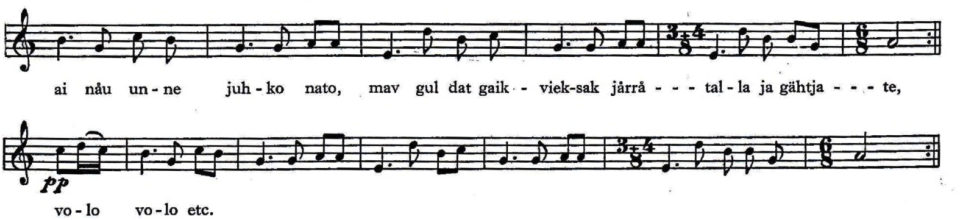

The joijk used in the symphony is identified by Peterson-Berger as a prayer to “Radien Attje: överguden”. There is some uncertainty surrounding this joijk, as it has sometimes been called, or possibly mistaken for, a prayer to the female god Sarrakka, but as both Peterson-Berger in 1917 (and onwards) referred to it, and Tirén in 1942 published it, as Radien Attje, this may be a later or separate confusion. Radien Attje was, according to Sami lore, “the almighty God” (“den rådande guden”), one of the three gods living highest up in the galaxy, and the text for the joijk, as published in Tirén’s collection of 1942, is:

The Heavenly father, the Almighty, in whose mightiness the whole world is; the world is as small as a ball, which the Almighty turns and watches. He is as a father who watches the playing of his children and punish them, when they do wrong; that he does in his mercy.[46]

It seems remarkable that Peterson-Berger would have invented a theme of such close resemblance to a later documented joijk, but Peterson-Berger is in print adamant that he had not encountered any Sami music before 1912 (Arnljot was written 1907–09), and we have no means (currently) of proving differently. What we do have is a joijk selected for the central movement of the symphony which Peterson-Berger interpreted as a prayer to the “God above”, and whose musical material is closely connected with a theme which for Peterson-Berger had connotations with both the wilderness of the Jämtland mountain region and a representative of a people often seen as living closer to, and unconditionally within, the landscape of this region.[47] The importance of this joijk and what it is understood to express is underlined further when Peterson-Berger uses it again in the last movement of the symphony, explicitly in 1917 equating it with a wish that “the magic of the Lapland nature would not be lost through the developments it was being subjected to” (Peterson-Berger 1917), and allows the symphony to end on fragments of this prayer. Suggesting that “God” for Peterson-Berger is nature, the landscape itself, would not only rest on grounds slightly too tenuous, but would corrupt the hierarchy between these two entities for Peterson-Berger. The “prayer” in the third movement nonetheless reveals the core issues of the symphony: that of finding an approach to the Lapland landscape which could incorporate the deeply held reverence and the nostalgia the National Romantic aesthetic imbued it with, the preservation of its indigenous cultures and representations of heritage, as well as the pragmatism and practicality of modern society.

Fig. 4a: “Radien Attje”, as published by Tirén, 1942.

Fig. 4b: “Wilderness-theme”, 1, from Arnljot, Act 2. © Abraham Lundquist AB Musikförlag

How else are we to understand the fanfares that open the fourth movement? Loud and energetic in high woodwinds and brass at first, then a softer echo in half-time in strings and bassoon, preparing the ground for the Finale’s first theme. But where the fanfares leave the possibility of a major tonality open (c-db-eb, in a possible Ab major tonality), the first theme settles it as F minor. Yet it is steady and defiantly energetic, its rhythmical pattern (see Fig. 2:X, first half only) lending it an air of muscularity and determination, and its “rightful” domination underlined when the orchestra returns to it in unison. Peterson-Berger’s text of 1918 relates this opening to the on-coming industrialisation of the Lapland area:

A shout of exhortation, an echo responds. Amongst the forests, the mountains and the waterfalls, an unfamiliar, unsettled life is beginning, something novel, foreign, from down there.[48]

That the method and result of this “invasion” of the northern landscape was a concern and a dilemma to Peterson-Berger, and one that he attempted to engage with in his music, is underlined again in the Norrbotten Cantata. The symphony topically shares three of its four sub-headings with the cantata, and Peterson-Berger writes in his introduction to the latter, published in Dagens Nyheter (31.7.1921) that the artistic idea centring on “the human cultivation’s penetration into the empty vistas of Lapland” is shared by both of them, as well as by Arnljot[49] (quoted in Fredbärj 1937 p. 249). In a later radio interview, he expands on what he has tried to achieve in the cantata, and refers to its third movement (entitled “Night in the wilderness & Day of cultivation”, combining Same-ätnam’s third and fourth movement in one) thus:

In the third act is depicted how this all happens. Through the dark, ancient sound of the rivers and the forests, through the ice-cold, long, silently sleeping polar night the sound of a horn fanfare suddenly rents the air from far away.[50] (Peterson-Berger 25.10.1931, quoted in Norrby 1937 p.145)

Peterson-Berger’s narrative descriptions and the horn fanfare both have close parallels in Same-ätnam’s fourth movement, and enable us to establish a connection between pieces that, in subtly different ways, try to engage with the changing conditions that Lapland was coming under, and that, anxiously and tentatively, allow themselves to hope that Lapland can yet survive the transformation. In the radio interview, ten years after the cantata, and nearly twenty after the beginning of Same-ätnam, Peterson-Berger seems optimistic:

[I]n burlesque hurry the new techniques march into this wondering land, but with the blissful music of the pastoral [in the fourth movement] one is clearly met by the composer’s joy that the metamorphic change nonetheless has not caused the irresistible beauty of the land to be destroyed.[51] (Norrby 1937 p. 146)

Already in Same-ätnam’s last movement, the desire to believe in a successful compromise is hovering. The last joijk is one which Peterson-Berger referred to as “so accurately depicting the nomad’s excitement over the vast expanses of cultivated land in Degerfors (Västerbotten)” (Peterson-Berger 1917). There is no trace of this tune, either in Tirén’s collection of 1942, or in Launis’s earlier collection, and it remains uncertain if title and tune are matched correctly. But as with the earlier “Sparks”, its relevance lies perhaps mainly with the ideas and emotions Peterson-Berger thought they expressed. The bright jolliness of the tune is emphasised by its orchestration of flutes (incl. piccolo), harp and piano, and taken together with the opening fanfare and first theme – as well as the notions in Peterson-Berger’s text and the previous movements – it seems to want to suggest an optimistic belief that harm will not necessarily come: that the approach to the landscape can be allowed to be multifaceted, operate on several levels, and entertain more than one perspective.

The fourth movement of Same-ätnam, with its clanging marches, Nordic folk dances, chorale-like rendition of the joijk, and frequent changes of tempi, several changes of keys, restless activity, banal jollity, and a beautifully lush ending, is then a vision but also a facing-up to our own role in the creation of and relationship with the landscape. Peterson-Berger and his contemporary context created a centrality of landscape for the Swedish national collective that was mostly achieved through isolated and individual, sometimes even unconscious, acts. With Lapland, however, all choices were conscious, all acts had a collective resonance and impact, and any engagement with the landscape required much more than a hike with rucksack and friends, or a passive gazing at its perceived beauty.

Same-ätnam. Lappland. The Sami name, and the Swedish name. A cultural reference and a geographical denominator, both with ideological dimensions. The use of both can only convey a dual stand-point. This is the land of the Sami, but it is also Sweden’s “Lappland”. It is simultaneously a spiritual landscape and a practical resource, a local moral responsibility and a mythical representation. It is a landscape that will yield framed vistas and physical experiences, that contains both ancient heritage and modern development, and that can evoke passionate emotional responses and practical brutalities alike. The “simple” pleasures of Lapland, its idyllic aesthetic, can no longer be the single viewpoint. In 1893 (away in Dresden) Peterson-Berger composed “A Mountain Hike”, a song-cycle imbued with the spirit of the Lapland “tourist” – a generic mountain landscape which rewards the physical efforts of its visitors with a one-dimensional spiritual well-being:

On the mountain there’s light and freshness and peace

On the mountain is wonderful to be[52]

The Lapland we meet in Same-ätnam requires a more complex response, as the concept of a passively “idyllic” Lapland is torn apart and the ideological landscape gives way to a multifaceted and multidimensional landscape with which to live, and not only to “see” . Composed as the future of the region was still very much unknown, the only way the “Symfonia lapponica” can end is by not ending, and the destabilising last Bb emerging out of the final F minor chord is ultimately the only comprehensive response for Peterson-Berger to give.[53]

References

Aminoff, Feodor (ed.) 1959: Svenska Naturskyddsföreningen 50 år. Historik; Register över artiklar publicerade i Sveriges Natur, Stockholm: Svenska Naturskyddsföreningen.

Arbman, Ernst et al. (eds) 1937, Festskrift till Wilhelm Peterson-Berger den 27 februari 1937, Stockholm: Natur & Kultur.

Arvidsson, Alf 1998: “Jojk som musikalisk råvara: användningen av samisk musik inom svensk konstmusik under 1900-talet”, in: Svensk tidsskrift för musikforskning, 1998, pp. 9–23.

Barton, H. Arnold 1994: A Folk Divided: Homeland Swedes and Swedish Americans, 1840-1940, Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell International.

Barton, H. Arnold 2002: “The Silver Age of Swedish National Romanticism, 1905–1920”, Scandinavian Studies, vol. 74.

Beite, Sten 1937: “Peterson-Berger som instrumental tondiktare”, in: Arbman et al. (eds) 1937, pp. 21–67.

Berger, John 1972: Ways of Seeing, London: British Broadcasting Corporation and Penguin Books.

Bohlin, Folke 1993: “Om jojkarna i Peterson-Bergers samiska symfoni”, in: Thule: Kungliga Skytteanska Samfundets årsbok 1993, Umeå: Kungl. Skytteanska samfundet, pp. 101–113.

Carlberg, Bertil 1950: Peterson-Berger, Stockholm: Bonnier.

Christensson, Jakob 2002: Landskapet i våra hjärtan: en essä om svenskars naturumgänge och identitetssökande, Lund: Historiska media.

Cosgrove, Denis & Daniels, Stephen 1988: The Iconography of Landscape, Cambridge University Press.

Crump, Jeremy 1986: “The identity of English Music: The reception of Elgar, 1898–1935”, in: Colls, Robert & Dodd, Philip (eds), Englishness: politics and culture 1880-1920, London: Croom Helm.

Daniels, Stephen 1993: Fields of Vision: Landscape imagery and national identity in England and the United States, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ehn, Billy et al. 1993: Försvenskningen av Sverige: det nationellas förvandlingar, Stockholm: Natur & Kultur.

Engström, Bengt-Olof et al. (eds) 2006: Wilhelm Peterson-Berger, en vägvisare, Möklinta: Gidlunds.

Eriksson, Gunnar 1997: “Synpunkter på Musiken i Sverige”, in: Svensk tidskrift för musikforskning, 1997:2, pp. 101–105.

Erlandsson-Hammargren, Erik 2006: Från alpromantik till hembygdsromantik: Natursynen i Sverige från 1885 till 1915, speglad i Svenska Turistföreningens årsskrifter och Nils Holgerssons underbara resa genom Sverige, Hedemora: Gidlunds förlag.

Fagerstedt, Otto & Sörlin, Sverker 1987: Framtidsvittnet: Ludvig Nordström och drömmen om Sverige, Stockholm: Carlsson.

Fredbärj, Telemak 1937: “Bibliografi over Peterson-Bergers verk”, in: Arbman et al. 1937, pp. 237–302.

Frykman, Jonas & Löfgren, Orvar 1979: Den kultiverade människan, Lund: Liber läromedel.

Grimley, Daniel 2006: Grieg: Music, landscape and Norwegian identity, Woodbridge: Boydell.

Grimley, Daniel 2010: Carl Nielsen and the idea of Modernism, Woodbridge: Boydell.

Hedwall, Lennart 1983: Den svenska symfonin, Stockholm: AWE/Geber.

Hepokoski, James 2009: “Fiery-pulsed Libertine or Domestic Hero? Strauss’s Don Juan Reinvestigated” (1992), in Music, Structure, Thought, Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 213–271.

Jacobsson, Benny 1999: “Skolans konstruktion av landskap”, in Bebyggelsehistorisk tidsskrift, no. 38.

Jacobsson, Stig 1998: liner notes to Wilhelm Peterson-Berger, Symphony no. 1 and Suite Last Summer, cpo 999 561-2.

Karlsson, Henrik 2006: “En sal mot aftonen belägen”, in: Engström et al. 2006, pp. 72-89.

Koerner, Lisbet 1999: Linnaeus: Nature and Nation, Harvard University Press.

Källén, Christer 1979: “Ett P.-B.-monument och dess tillkomst”, in Musikrevy, vol. 34, no.1, 1979, pp. 2–4.

Lagerlöf, Selma 1981: Nils Holgerssons underbara resa genom Sverige, Stockholm: Bonniers Juniorförlag (1906–07).

Lagerroth, Ulla-Britt 2006: “Arnljot som nationalopera”, in Engström et al (eds), pp. 90–105.

Launis, Armas 1908: Lappische Juoigos-Melodien, Helsingfors: Druckerei der Finnischen Literaturgesellschaft.

Lundberg, Dan & Ternhag, Gunnar 2005 (1996): Folkmusik i Sverige, Hedemora: Gidlunds förlag.

Löfgren, Orvar 1999: “Rum och rörelse. Landskapsupplevelsens förvandling”, in: Bebyggelsehistorisk tidsskrift, no. 38, 1999, pp. 31–42.

Moore, Jerrold Northrop 2004: Elgar, child of dreams, London: Faber.

Norell, Gösta 1991: Wilhelm Peterson-Berger och dikten. 1: En konstnärsstudie, Arboga: Norrlandsförlaget.

Norrby, Johan 1937: “Inför Peterson-Bergers körer och kantater”, in Arbman et al. (eds) 1937, pp. 132–153.

Olsson, E.W. 1937: “Peterson-Berger i Jämtland”, in: Arbman et al. (eds) 1937, pp. 227–233.

Oscarson, Christopher 2007: “Linnaeus 1907: Oscar Levertin and the Re-invention of Carl Linneaus as Ecological Subject”, Scandinavian Studies, Winter 2007, vol. 79, no. 4, p.405-426.

Peterson-Berger, Wilhelm 1913: “Lapsk musik”, in Dagens Nyheter, 28 April 1913, in Peterson-Berger 1942.

Peterson-Berger, Wilhelm 1917: “Nytt svenskt tonverk på operan: Same-ätnam av Wilhelm Peterson-Berger”, in Dagens nyheter, 9 December 1917.

Peterson-Berger, Wilhelm 1918: “Same-ätnam. Lapplandssymfonien som framföres vid aftonens konsert”, in Dagens Nyheter, 19 March 1918.

Peterson-Berger, Wilhelm 1942: Om musik [re-print of articles previously published in Dagens Nyheter], Stockholm: Bonniers.

Peterson-Berger, Wilhelm 2003: Fjällminnen: samlade artiklar [Orwar Eriksson and Gusten Rolandsson (eds)], Östersund and Jengel: Wilhelm Peterson-Berger-institutet.

Pettersson, Carl Anton 1866: Lappland. Dess natur och folk. Efter fyra somrars vandring i bilder och text skildrade, Stockholm: Fritze.

Pettersson, Richard & Sörlin, Sverker (eds) 1998: Miljön och det förflutna: landskap, minnen, värden, Umeå: Umeå universitet.

Riley, Matthew 2007: Edward Elgar and the Nostalgic Imagination, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ronström, Owe & Ternhag, Gunnar (eds), 1994: Texter om svensk folkmusik – från Haeffner till Ling, Stockholm: Kungl. Musikaliska akademien.

Schama, Simon 1995: Landscape and memory, London: HarperCollins.

Sehlin, Halvar et al. 1985: 100 år med STF: utställning i Uppsala universitetsbibliotek 15 february-15 maj 1985, Uppsala: Uppsala universitetsbibliotek.

Spencer-Longhurst, Paul 2009: Northern Lights: Swedish Landscapes from the Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, exhibition catalogue, The Barber Institute of Fine Arts/University of Birmingham, 27 February – 31 May 2009.

Svenska Turistföreningen (STF): Stadgar för svenska turistföreningen, 1891.

Svenonius, Frederick & Bergqvist, Olof (eds) 1908: Lappland, det stora framtidslandet, Stockholm.

Sörlin, Sverker 1988: Framtidslandet: Debatten om Norrland under det industriella genombrottet, Stockholm: Carlsson.

Ternhag, Gunnar 2000: “Om sambandet mellan folkmusikinsamling och tonsättning av folkmusikbaserade verk”, in: Svensk tidsskrift för musikforskning, vol. 82, pp. 57–78.

Ternhag, Gunnar 2006: “Folkmusik är aldrig gubbmusik”, in: Engström et al. (eds) 2006, pp. 139–156.

Thomsen, Bjarne T. 2007: “Lagerlöfs litterære landvindning”, Amsterdam: Scandinavisch Instituut.

Tillman, Joakim 2006: Ledmotivstekniken i Arnljot, in Engström et al. 2006, pp. 106–138.

Tirén, Karl 1942: Die lappische Volksmusik: Aufzeichnungen von Juoikos-Melodien bei den schwedischen Lappen, mit einer Einleitung von Wilhelm Peterson-Berger, Stockholm: Geber [i kommission].

Trend, Michael 1985: The Music Makers: Heirs and Rebels of the English Musical Renaissance, London: Weidenfield & Nicholson.

Various authors 2007: Elgar, An Anniversary Portrait, London: Continuum.

Wallner, Bo 1956: “Till den himmelske fadern: en voullah som symfoniskt tema”, Svensk Tidsskrift för Musikforskning, vol. 30, pp. 87–110.

Wylie, John 2007: Landscape, London & New York: Routledge.

Scores

Peterson-Berger, Wilhelm 1914: Arnljot, vocal score with German translation, Stockholm: Abr. Lundquist.

Peterson-Berger, Wilhelm 1922: Same-ätnam. Lappland. Symfoni no. 3, full score, Stockholm: Elkan & Schildknecht.