From Yoik to Music: Pop, Rock, World, Ambient, Techno, Electronica, Rap, and…

K. Olle Edström

[1] Introduction and six cases

The first time I came to the small village of Jokkmokk, situated just above the arctic circle in Northern Sweden, was a lovely summer day in June 1974. For some years, I had been interested in Sámi culture and especially in Sámi yoik, traditional unaccompanied songs, consisting of a few short motives that are repeated with text or more often a mix of words interspersed with syllables. (cf. footnotes 3, and 5–7). During these years, I worked as a musician and a music teacher.[1] To most of my friends, my interest in Sámi culture was a bit strange. They wondered what had caught my interest, and why I had devoted more and more time listening to yoik, learning the Sámi northern dialect, and reading books about this culture far away somewhere in Northern Scandinavia.[2] As far as I remember, I could not give them an answer that satisfied them. I suppose that I was just curious and somewhat confounded that I knew almost nothing about this culture and yoik.[3] As I remember it today, I was at the time influenced by Alan Merriam and the concept of acculturation, which, at the time, I understood as a term for the cultural and musical influences the dominant Scandinavian cultures had had on Sámi yoik tradition.[4] However, as I got out of the bus at Jokkmokk, I had not foreseen the great variety within the Sámi yoik/musical culture that I was to meet already in the first week.

Looking back today on the different yoik experiences I encountered in Jokkmokk, I find six different cases particularly interesting. I offer these as points of departure before I turn to the major objectives of this article.

I stayed with the family of the local priest, the Sámi Johan Märak, who was an accomplished yoik-performer, “yoiker,” within the stylistic northern yoik dialect.[5] He was kind enough to yoik several of the yoiks that he had recorded and for one of those he also wrote down the words and syllables which I then used in my transcription of the yoik. One of these days in Jokkmokk, I visited the Sámi painter Lars Pirak, also an accomplished yoik-performer. We sat for several hours in his studio as he performed many of his most well-known yoiks introducing them verbally and yoiking them, totally absorbed in the music/lyrics. In contrast to Märak’s yoiks, his yoiks were all in the southern yoik dialect.[6] From a stylistic point of view these experiences were more or less known to me, but the emotional part of the experience in the live situation was something that I had not experienced before.

My third experience was rather unexpected: the musical style of the yoiks of Nils Pavval, a Sámi student at the folk high-school in Jokkmokk, was reminiscent of normal school songs, i.e., simple and tonal songs in major, songs in a style that all school children in Sweden had sung up till then in the twentieth century. Certainly I had learnt that some yoiks from the Southern Sámi areas recorded on the yoik records published by The Swedish Broadcasting Corporation strongly resembled Swedish folk songs or songs in major mode, but I was not prepared for the fact that Pavval’s repertoire consisted predominantly of major-mode songs. His texts, which were often in Swedish, were mostly tales about his life and Sámi experiences.[7]

I encountered my fourth experience as I went to a party at the local folk high school where everyone—Sámi and Swedish youth—yoiked some northern-dialect yoiks together. Consequently, yoiks could also be used as a kind of party songs at mixed Swedish and Sámi parties. I learned from the Sámi poet Paulus Utsi that this kind of singsong communion had been going on for a few years. The lyrics were mostly just syllables. Being present at the Junior College (Folkhögskola), I also became aware of the ongoing political-ideological debate among the students and teachers regarding the situation and status of the Sámi population in Scandinavia.

My fifth experience was rather unexpected as I was able to find some recorded material from the 1960s at the Sámi museum in Jokkmokk, among these a recording from an informal concert at the museum, where among others a young Sámi, Nils-Aslak Valkeapää (born in 1943), performed yoiks of the northern style in a songlike, rubato-style manner, with just syllables, accompanying himself on a guitar.[8] He played slowly strummed chords (tonic and dominant) on a poorly tuned guitar. I learned that he had grown up in a reindeer herding family and was a fine performer of yoiks as well as a certified schoolteacher.

In retrospect, I can now place these encounters on an open line where yoik as part of traditional Sámi culture is placed towards the left and music belonging to a Western modernity to the right. Thus, to the left, I place Märak’s and Pirak’s traditional yoiks performed in styles that I recognise as Sámi. The traditional functions of the yoik were Sámi (reference, group specific, sonic acts of remembrance etc.). To the right I place Pavval’s yoiks, which from a musical point of view rather sounded like Swedish songs with a style of singing that was Sámi only to some extent, but where the functions of the yoiks could still be referred to as predominantly Sámi. In the yoik-singsong, the functions were clearly a form of entertainment and a way of making contact through singing for the Swedes and Sámi at the party. The renditions sounded like yoik but the functions of these yoik-singsongs can probably be considered as both Swedish and Sámi. Many other popular non-Sámi songs were also sung, but party or community singing of this kind has never been practiced within traditional Sámi culture, as far as I know. The yoiks had been taken out of their previous Sámi context. Similarly, Valkeapää’s careful performance of yoiks with guitar accompaniment can be seen as a break with earlier Sámi performance practice, where yoiks were sung in solitude without an audience, to other members of the family or to friends. In a concert situation—including non-Sámi listeners—other functions emerged.

Although I did not fully realise it at the time, what I experienced during these summer weeks was the result of an ongoing discussion within the Sámi communities in Scandinavia, which affected the attitudes of the general Scandinavian society regarding the issues of Sámi self-rule and Sámi culture. Regarding the latter, it can be said that “a cultural turn” took place at this period within the fields of Sámi yoik and music, to which I now turn. I also found a record with Nils-Aslak Valkeapää at the Sámi museum in Jokkmokk, a record that was to be used by various artists. The main objective of this article, thus, is to discuss the sounding consequences of this cultural turn and the ongoing change within the Sámi yoik and musical arena, as well as how this change and related concepts, such as world music and postmodernity, can be understood from a Sámi perspective. The emphasis, however, will be more on empirical matters such as musical traits than on how different concepts of change could be understood. Moreover, as I give an overview of the stylistic changes within popular Sámi music up until today, I will concentrate on four artists or cases that are positioned in different places within an expanding Sámi musical field.

Before I continue I will present a background against which the positions of yoik and music within modern Sámi society can be better understood. “Scandinavia” used as an umbrella concept for Norway, Sweden, and Finland, rather than the typical definition Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, can easily deceive readers to believe that the conditions for the Sámi people in these three countries are the same, but that is not the case at all.

[2] Sápmi in Scandinavia in the 70s

Looking back on the socio-historic situation it is obvious that Sweden in the 1970s was characterised by an expanding economy with many large industries, forestry and mining companies. There was major immigration of labour from Finland but at this point increasing numbers of immigrants in search of work arrived from Yugoslavia. Among the Sámi population a little more than ten percent was working with reindeer herding, an industry or rather a livelihood that only Sámi people had the right to pursue. This was also the case in Norway, where shipping, fishing, forestry and smaller enterprises were the major industries. The oil industry was just starting up. In Finland, smaller ventures and forestry were the dominating industries, but there the Sámi did not have the exclusive right to reindeer herding. Finland had few immigrants.

From a geopolitical point of view, there were major differences between the countries. Norway gained independence from Sweden in 1905. The strong nationalist feelings had been strengthened due to the occupation of Norway by Germany during the Second World War. After the war, Norway joined NATO.

After hundreds of years of Swedish rule and one hundred years as a Russian protectorate, Finland proclaimed itself a free nation at the end of the First World War. Growing nationalist feelings had emerged during the nineteenth century, and the linguistic and cultural affinity of the Finnish population with other Finno-Ugric peoples was emphasised. Armed conflicts between the bourgeoisie and socialist groups marked the first years of the newly formed nation, and twenty years later Finland was attacked by the Soviet Union at the beginning of the Second World War. An attempt to regain lost areas failed later during the war. Towards the end of the war, Finland attacked the troops of its earlier ally Germany, which made the retreating German army set many thousands of houses as well as innumerable bridges and boats in Northern Finland and Norway on fire. As a group, the Sámi population in both Norway and Finland managed much better during the war in comparison with the general population. After the war nationalist feelings were consolidated and Finland was established as an independent and neutral country, a country though, which shared it eastern border with the political opposite of the Western world, the Soviet Union.

A neutral country, Sweden was not involved in any of the two world wars. Swedes could look back on their history during which Sweden had always been an independent country, but one from which a very large proportion of the population had emigrated, mainly to the United States. In comparison with Norway and Finland, nationalist feelings in Sweden were considerably weaker.

The ideological protest movement against the existing society, which had resulted in various student revolts questioning existing values, was one of the factors that also affected the Sámi population in the 1960s. The Sámi quest to make the Sámi language officially recognised and admissible in the schools, as well as to establish specific political and social rights for the Sámi in relation to the general society of the Scandinavian countries was intensified during these decades. The Sámi population of about 5,000 inhabitants in Finland gained such rights already in 1973, whereas in Norway with approximately 60,000–100,000 Sámi inhabitants a Sámi self-government council (Sameting) with considerably more political power was established in 1987. A similar (quasi)-self government council was not granted the 15,000–20,000 Sámi inhabitants in Sweden until 1993.

As I have shown in this short introduction the social and cultural processes of change behind the changes that occurred within Sámi yoik and contemporary popular music partly had different political and demographic points of departure in the three countries. In Norway, characterised by a more nationalistic outlook, the Sámi population was a large minority, which got a larger political and cultural self-influence at a much earlier stage than the Sámi population of Sweden, where nationalistic views were much weaker and the general population was twice as large. The position of the Sámi as a minority group in Norway was considerably stronger than in both Sweden and Finland, but because of their Finno-Ugric language, the Sámi of Finland already had a different position: Sámi culture and yoik as a cultural expression were never questioned to the same extent in Finland as they were in Sweden and Norway. From the 1970s, Yoik and Sámi pop music could be heard not only within families who yoiked or played themselves, but also by everybody who had access to a radio or a gramophone. As other youths, Sámi adolescents could listen to the new youth music on the radio/gramophone/juke-box. One complicating factor in connection with yoik was that for generations it had been regarded with profound scepticism within the Christian Laestadian movement, a religious movement that many of the Sámi population of the northern areas had joined. Laestadians did not yoik. For them yoik was a way of expression going back to pre-Christian times, and it was seen as a sinful practice. It was regarded with disapproval if school children yoiked during school hours, and this was even explicitly prohibited in a large municipality such as Kautokeino. However, even for families of the Laestadian faith it was difficult to “protect” the new generations from other listening experiences than the “correct ones,” i.e. psalms and hymns. In the schools, the teachers kept singing the usual European school songs and Nordic folk songs together with the children.

The general cultural values of the 1970s also implicated that there was a clear division between the values of different forms of culture in the general society.[9] Within the musical culture in the three countries, both older art music and modernistic art music had high cultural value and standing. The groups and power structures that generally had the precedence of interpretation in the twentieth century also highly valued their national folk music. The increasingly dominating forms of popular music transmitted by mass media had been regarded as much too commercial, especially in the 1960s, but was gradually tolerated and finally celebrated in the 1990s.

In the 1960s and 1980s, traditional yoik performed by Sámi was still not held in great esteem within the general Scandinavian society, regardless of whether or not people had heard yoik. The majority of the population of the three countries lived in the southern parts where there was little thought of the Sámi and where individuals of Sámi origin seldom drew attention in their daily lives to the fact that they were Sámi. At the beginning of the 1970s, the expectation that the Sámi should be less explicit about their Sámi origin was still quietly expressed, but from this time and onwards, major changes occurred. As is well known, the 1960s and 1970s were times when European society, dominated by middle-class values, was attacked by various left wing movements where younger generations rebelled against older generations.[10] This also affected the Sámi communities and, as stated, the 1970s can be seen not only as a cultural turn but also as a political turn for the Sámi.

[3] From yoik to folk & yoik, pop & yoik, rock & yoik

The record, an LP, I found at Jokkmokk contained traditional yoiks sang by Valkeapää accompanied by Finnish musicians playing drums, bass and guitar. This record, Joikuja, had been released already in 1968 and, of course, it could be seen as my sixth experience.[11] One popular yoik was the traditional “Early in the morning.” The lyrics starts: “early in the morning he proposed in Karasjok, and at dawn he yoiked in Kautokeino…”[12] The yoik was accompanied by a guitar, drums and a bass that transformed the Sámi experience; it sounded like a mixture of yoik and a pop tune. On this track, there are also sampled sounds—reindeer lowing and the barking of dogs.[13]

There were probably several younger Sámi in the 1960s, who tried to yoik to the accompaniment of a guitar or a piano. As the record Joikuja could be bought both within and outside Sámi culture, it afforded all sorts of use. It could be played in the homes of the Sámi, listened to outside on transistor radios on programs broadcast on Sámi radio etc. New forms of popular African-American and Anglo-American music, so called youth music, could also be heard on the radio, and as new forms of use such as dance music, background music etc. developed, the functions of the music changed.

The melodies on Valkeapää’s record as such were all based on traditional yoiks and the lyrics were in the Sámi language. However, the sounding result could be experienced as modern popular Sámi music, quite similar to contemporary popular (Western) music.

During the 1970s the number of young Sámi persons trying to yoik and play the guitar increased.[14] Several bands were formed and there was an opportunity to make recordings, sometimes with Norwegian or Finnish musicians. To the six different experiences or types of yoik and song that I had met in Jokkmokk, I could soon add so many new forms that I lost track—some melodies sounded as folk-pop and yoik, some as rock and yoik, Latin and yoik, jazz and yoik, or as ordinary country and western songs, as blues, etc.[15] The words though, reflected the thoughts, frustration and experiences of being a minority people traditionally looked down upon by the majority people.

Many Sámi of the older generations had a hard time accepting the modern Sámi music. A debate about the Sámi authenticity of the music started. Even if both sides agreed on and liked the lyrics, many of the older generations could not penetrate the musical surface. Detractors among them also argued that many of these records were made from sheer commercialism, while another camp saw nothing wrong in the yoik developing and blending it with different other idioms. The members of the younger generations, on the other hand, saw the modern popular Sámi music as their own music. To them, this music was modern Sámi music and yoik was old Sámi music.

The debate about what was possible, not to say permissible, was especially intense and public in connection with the album Lĺla, published in time for the Christmas shopping rush in 1980 by the Sámi Mattis Heatta and the Norwegian Sverre Kjellsberg as a follow up to their contribution to the European Song Contest. The many yoiks on this album were accompanied in a variety of ways. One was turned into a pop ballad, another performed in Latin American style. Still another traditional yoik, “Ovlaš Ovla,” evoked a mood reminiscent of the German Hit Parade of the 1970s.[16] To many Sámi there was little to remind them of the essence of yoik, while another large body of opinion saw nothing wrong in these arrangements. To what extent and for whom these yoiks still retained a feeling of Sámi authenticity was an open question.

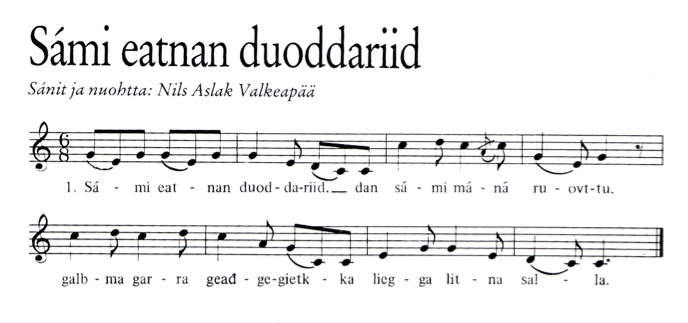

If we, however, return to Nils-Aslak Valkeapää and take his career as an example, he continued to explore new paths, mainly well within the Sámi soundscape. In the 1970s, he started to work closely with Finnish jazz musicians, among them the composer and tenor saxophonist Seppo Paakunainen and the composer and pianist Esa Kotilainen. The music reflects this collaboration; pentatonic yoiks were used as a basic element of improvisation in jazz-rock arrangements. An early example is the album Sámi eatnan duoddariid (1978). The yoiks performed by Valkeapää are integrated into elongated developing musical forms (up to eleven minutes). The yoik “Juhan” (A:3) can be used as a typical example. This yoik, which is in triple meter, is first performed on a Hammond organ, then backed up by a bass clarinet, after which Valkeapää yoiks in unison with the bass clarinet. In the background there are different types of percussion: rustle, bells and indefinable “synthesiser sounds.” Gradually, an instrumental solo starts on the tenor saxophone and the yoik is played repeatedly on the bass clarinet. These roles are then taken over by a moog (solo) and a Hammond organ, after which Valkeapää starts to yoik again, backed up by various instruments. Gradually the tenor saxophone takes over with a new pentatonic solo, after which the intensity is reduced, the triple metre ceases and the tenor saxophone plays a finishing “jazz cadence.”[17]

In the 1980s African ethnic instruments such as mbira, gongs and drums were also used which gave the yoik-arrangements an African feeling. On other recordings, the sounds of nature itself provided an important dimension. The lyrics could be a traditional mix of syllables and a few words or newly written lyrics consisting mostly of poetry in free forms. In still other productions, he embedded his yoiks in contemporary electronic compositions flavoured by a natural Sámi soundscape. Together with his Finnish collaborators, he also recorded bird songs and calls and combined these structures with sounds from the Sámi landscape into a bird symphony. Paakunainen also wrote a quasi-Sibelius-sounding symphony, interspersed with yoik performed by Valkeapää.[18]

Valkeapää also wrote poems, produced a book about the Sámi cultural heritage, staged a multi-media performance that made a great impact both among Sámi and non-Sámi audiences, made concerts in Scandinavia as well as in most parts of the world. The very fact that he formed his performances around poems, photographs, sounds from nature and yoik dressed up in various sensual constellations resulted in that he found listeners among both the Sámi, who could relate to the various parts and the whole, as well as non-Sámi audiences, who were not bored by only hearing Sámi yoiks arranged and performed within the musical world and soundscape of Paakunainen and Kotilainen. As he was not usually seen by the general Scandinavian community as having an obtrusively Sámi agenda, his art was gradually recognised as having major cultural values, especially, of course, within the Sámi community.

His art, the style of his poetry, the illustrations and design of the books, the inner complexity of the music and his sensual style made it possible to place him along an open line from a Sámi folk style to a more artistic and contemporary Western form of expression.

The picture was further complicated by how much importance each listener put into the concept Sámi, in the sense of a traditional culture, on the one hand and the concept of Western contemporary modernity on the other. The double contradiction concealed here implied that Valkeapää’s work could be comprehended in different ways depending on the ethnic background and identity of the listener on the one hand and, on the other hand, how the value and position of the work was regarded—as a traditional Sámi or a modern Western form of expression.[19] For a Scandinavian listener/reader he could alternately, or even simultaneously, be both an “authentic Sámi” and a “European modernistic artist.” [20]

Valkeapää received the Nordic Council’s prestigious literary award in 1991. The record Goase dušše (The Bird Symphony) was awarded the internationally renowned Prix Italia in 1993.[21] Even at the inauguration of the Olympic Winter Games in 1994, he performed a newly composed yoik.[22] Until his death in 2001, he was one of the most influential Sámi personalities.

With the exception of Valkeapää’s music and Haetta’s & Kjellsberg’s entry for the Eurovision Song Contest, these various forms of modern Sámi music seldom reached audiences outside the Sámi population. One of the foremost and obvious reasons for this was the language barrier, but in addition, the artistic standard and the musical competence within the Sámi population depended on a small number of inhabitants. Many of the Sámi artists making their débuts during these years, and also later, had what I would call a mediocre musical ability. This was only to be expected. The Sámi population was small, and there is hardly any reason to believe that the same number of equally talented non-Sámi artists would have received economical support from the community to produce LPs and CDs as among the Sámi. In other words, the support given to the production of Sámi recordings, primarily by the Norwegian government, made it possible for Sámi artists to make records and productions that otherwise would never have been realised in a competitive mass media industry.

In summary, since the 1970s, side by side with the traditional yoik, a number of Sámi artists, predominantly citizens of Norway and a few from Finland—mainly taking their initial point of departure in yoik—tried out new musical ideas by mixing yoik with various stylistic traits and patterns of accompaniment from contemporary Western popular music. A further result of this was that songs with Sámi lyrics were written within these genres.[23] These changes brought about the development of an awareness of a double indigenous musical culture within the Sámi community (yoik and modern music). At the same time, the value of this change was attributed different significance depending on factors such as age group, ideology and religion. At the same time Valkeapää extended both the cultural and musical fields of yoik through his work, placing his musical style mixes within a multi modal context, which meant that the experiences were well positioned within both traditional Sámi culture and in a Western artistic field—as art.

* * *

Whereas Valkeapää’s name has been associated with yoik, electronic-ambient sounds & yoik, jazz-rock fusion & yoik, symphony & yoik, the career of the other Sámi “superstar” Mari Boine Persen (born in 1954) started with pure rock and ballads.[24] She released her first LP Jaskatvuoňa manná (After Stillness) in 1985. Her parents were Laestadians. When she started at a teacher training college, she tried to disassociate herself from her Sámi background, but soon afterwards, questions of identity became more important.[25] She also started to write lyrics, and one of her first efforts was to put lyrics to John Lennon’s “Working Class Hero.” Her music became a means for her Sámi awakening, and she developed as a rock singer. Most of the songs on the record After Stillness are her own. The first tune was a deliberate kick at the Norwegian government. The lyrics start:

Dear sirs, high in rank far away in Oslo—do you have some time for us—we watch the TV every night—but we never hear Sámi, our own language—Dear sirs, far away in Oslo—do you have some time for us.[26]

This song was one of few that were not by Mari Boine. It was sung to a melody composed by the Australian composer A. Strals, and had been a hit in Australia in the 1970s. There it was performed by Sister Mead, a Catholic nun. The lyrics were familiar enough. Instead of “fathers in Oslo” Sister Mead sung about: “Our Father who art in heaven…” A Sámi rock star was born.

[4] From rock to “world music”

Because of the rock style of her first record, Mari Boine Persen made herself a name among both the Sámi and the Norwegians, even if the lyrics were very critical regarding the Norwegian attitude towards the Sámi. In 1989 she released the record Gula Gula (Listen, listen). Her Sámi lyrics were still highly political but her music had changed. No doubt this also had to do with the professional musicians taking part in the recording, among them the Swedish all-round folk musician Ale Möller and the Peruvian Carlos Zamata Quispe. In an interview, she agreed that her songs on this record could be labelled as world music, but that she did not care much about labels.[27] Mari Boine Persen type of “world music” on this record could be described as a mixture of rock with quasi-West-African rhythms, with short phrases sung in a kind of Sámi/native North-American technique and with rather few harmonies or drone-like harmonies. There are some improvised solos by the musicians. Instead of common electric guitars and rock percussion, the musicians play “ethnic” instruments such as West African drums, mbira, bouzouki etc. In her lyrics, she often describes her negative experiences within the Norwegian society as well as personal experiences of love and despair. Because of the success of this record Mari Boine was no longer just a Sámi or Scandinavian celebrity. In 1991 the Scandinavian Airlines magazine wrote:

In England the English record company “Real World” owned by Peter Gabriel got interested in “Gula, gula.” The British launch was followed by overwhelmingly positive critique in well-known publications such as the Guardian and the New Musical Express. (SAS-Magasinet 1991 No. 2).[28]

As another Norwegian journalist expressed it in a more cynical way, after this record she was “among the most ‘politically correct’ artists to enjoy” (Puls No. 4, 1993).

On her following albums in the 1990s, such as Goaskinviellja, 1993 (Eagle Brother, /Lean MDCD 62/), and Leahkastin (Sonet MBCD 94),[29] 1994, a similar world music atmosphere can be recognised. In comparison to Gula, Gula similar sparse and falling melodic lines and the charismatic intensity of her voice can be noticed. Often, the texts do not have the same aggressive energy, which is particularly evident on the first album. The texts on the earlier albums are also more similar to the scantily worded texts of traditional yoiks. She often repeats many words and phrases, which eventually might be experienced as not conveying any meaning, as “yoik syllables.”[30]

In the interview in Puls she brought up the intended difference between the style of the texts on Gula, Gula and Goaskinviellja, and said that on “Gula, Gula I cried out my inner mind and was a spearhead for everybody,” whereas on Goaskinviellja “the aim has been to tread more elegantly, but affect something inside the listener, to make her shout and scream instead” (Puls, No. 4 1993).[31] Already in Goaskinviellja the texts are more personal and less critical of society, and in a very personal style she makes more use than previously of the two clearly different registers of her voice.

To most European listeners Mari Boine was probably heard as an international artist of Sámi origin. In March 1994, the newspaper The European (25–31 March 1994) wrote that her latest album consists of a “remarkable fusion of folk, jazz and rock. The sparse arrangements have a receptive audience among those whose taste tend towards the ambient and ethereal.” The headline read: “Play it again Sam.” Consequently, the records have also been released on different international labels.[32]

Already on Gula, Gula she had found a kind of ethnic voice and a technique of her own. The quality of her voice always carries the songs, but her singing style, technique and intonation bear very little resemblance to the way Northern Sámi yoik is traditionally sung (Cf. below).

Whereas many of the texts on the early albums were clearly ideological, albums from the present century increasingly have texts with elements of a personal, loving and more general character. Thus, the lyrics of the twenty-first century productions are dominated by a personal voice, texts about the conditions of life and an approach to a pre-Christian Sámi figured world. This is evident on the record Gávcci jahkejuogi, 2001 (Eight Seasons, Universal 017019-2), where all lyrics are printed in both Sámi and English. The record features musicians with whom she has been co-operating for a long time, such as the bass guitar player Roger Ludvigsen and the woodwind musician Carlos Zimbabwe Quispe, but also new musicians such as Svein Schultz, bass guitar, and Bugge Westertoft, synthesizer and programming. Mari Boine’s particular melodic world is clearly present on the record, but there are also songs with a more yoik-like structure than on earlier albums. One of these song-yoiks is “Duottar rássi” (Tundra flower) played in a slow shuffle/country-and-western style. There are also elegiac and beautiful slow ballads and a freely interpreted Norwegian hymn.[33] Mari Boine sings some of the songs in English. The CD sleeve information includes quotes from Ernst Manker’s classical presentations on Sámi history.[34] Some of the lyrics also relate to early Sámi cultural history.

Maybe this change is even more evident on her recent album Idjagieða, 2006 (In the hand of the night, Universal/Lean CD), which includes a great number of musicians. Mari Boine herself has only made two of the twelve songs on the album and five more together with some of the other musicians. In addition, the Sámi guitar player Georg Buljo has made three songs and Svein Schultz has made two songs. [35] It should be noted that the producer Schultz has the overall responsibility of the album. The album includes many Mari Boine songs, which are often in the key of B-minor or in a Doric B-mode such as “Vuoi, vuoi, mu” (music by Georg Buljo and lyrics by Rauni Magga Lukkari).

Mari Boine’s interest and direction towards a pre-Christian Sámi figured world is manifested on the album by many of the songs, among them her own music to Karen Anne Buljo’s “Davvi bávttiin” (On the fells of the north). The song clearly reflects the musical atmosphere that is often evident in Mari Boine’s songs. It starts with Mari Boine singing in a restrained, vulnerable distinctively personal voice about the longhaired shaman girl:

Music example 1

In the background vague, environmental sounds can be heard of reindeer and Sámi reindeer herds, at 0:30 a few undecided notes from a synthesizer are heard. A rhythmic groove is added at 0:40 (BPM=110) where the same melody is repeated. When she reaches the final phrase of this part the sound is considerably developed by male voices singing the same phrase (see the musical example below). At first, the phrase is backed up by soft chords on a synthesizer (the chords are Dm, Em/g, Dm, G no third). At 1:28 this part or section returns, this time also supported by a powerful bass line in the lowest register and a slightly new succession of chords. It gives the melody a vigorous character:

Music example 2

The first part returns and so does the second part, which however is reiterated from 4:18 until the end (6:48). Even if the dynamics stay more or less the same, it should perhaps get the listeners to envisage this elongated part as a sort of trance arousing song.

Now and then, the shaman girl, borrowing the voice of Mari Boine, improvises melody lines over the male voices. This goes on and on and on. Svein Schultz, however, told me that when composing the song he sought an expression that he termed a lullaby for adults. Furthermore, during the performance at the festival, they hoped that the audience would be caught by the above phrase and sing along.[36] Both my interpretation and the musician's, though, seem plausible as the lyrics tell about “…the shaman daughter trance sleeps…” and “cradles the child chilled by the night…”

There are also some tranquil, simple and overpoweringly beautiful songs such as “Geasuha” (Irresistible, Georg Buljo and Rauni Magga Lukkari).

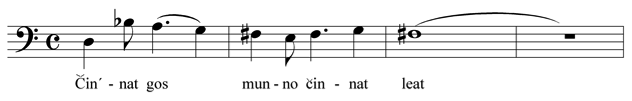

However, there are also some songs that to some extent are different from previous tunes. The introduction to “Gos bat munno čiŋat leat?” (“Where did all the colours go?” Svein Schultz and Boine) gives a different impression as it starts with a choir of male voices singing, which I perceive as the introduction to a part of an art music mass. But after a short while (at 0:28) the mode is changed as an electric guitar comes in against a “dark” groove (BPM=72 in a “free flowing” mode):

Music example 3

Against this structure or accompaniment, Mari Boine (at 0:50) starts to sing, in a (for her) low-pitched voice, a tune that emphasises the mystical character of the composition. The lyrics pose the question of where the (Sámi) festive garments and where all the colours did go. It starts:

Music example 4

This song continues until 1:50 when she changes key floating over minor harmonies singing a sad phrase with the words: “Breathe me back to life, unchain and free me.” This second part begins:

Music example 5

Following this, part I (not the male choir, though) and II are repeated twice and the piece finishes on a B-minor chord.

* * *

[5]

As is well known, “world music,” or as it has been described “local music but not from here,” grew in international importance and sales in the 1980s.[37] As a rule, the basis for the production of “world music” is some form of traditional singing style or a type of music/song of an ethnic group, tribe or nation, and this is the case with Mari Boine’s music too. In almost all cases a rather standardised rhythm is added. Various instruments, for instance typical Western popular instruments such as guitar and saxophone together with a kora harp, a shakuhachi, a didgeridoo or almost any instrument at hand are combined in order to create a new sound.[38]

Mari Boine’s stylistic change in the late 1980s and her ongoing success in the 1990s, though, could not have happened had not both the Sámi and the non-Sámi followers increasingly been accustomed to the contemporary global trend for fusion that had been going on for decades.[39] She developed a following that, to use Mark Slobin’s expression, bonded to her sound and style.[40]

Already in 1997, Mari Boine stated in an interview that her musicians probably were more aware of the music they were influenced by than she was. The music, she said, was a mixture:

It is as if I have never thought “this is this kind of music and that is that kind” everything is a whole, and I am consuming it, and then it is mixed inside me to something new … I do not want to be too aware of where things come from … that would be censorship. I use intuition to a great extent. [41]

To the Sámi population, Sámi “world music,” songs with instruments, sounds and playing techniques, could thus be seen as yet another addition to yoik & pop, etc., whereas an international audience listened to it as world music. Today, more than twenty years later, many forms of world music, in my view, could be described as “pan-global” or maybe as “local music but not from anywhere.”

The fact than an increasing number of young people got access to computers during this period did not only make it possible for them to download unlimited amounts of contemporary music. It also led to a further change of the ontological status of the music. During the first half of the twentieth century, people realised that the music heard at home was disconnected from the place where it was played when they heard a live transmission on the radio. When listening to a gramophone record at home the listening experience was disconnected both from the time and place of recording. The sudden change that took place in the 1980s was that the music downloaded from the Internet was disconnected from both time and place, but in many cases also from a specific culture. Furthermore, as music now had become portable, it could be heard in headsets outside the homes of people. Music was no longer something that was directly played by musicians on acoustic instruments or sung live, music was now more or less always recorded and always accessible.

This change occurred simultaneously as general value scales and value norms regarding literature, musical genres, songs etc. were increasingly questioned, leading to a relativization and de-hierarchysation. To bring up two extremes as examples; was it the music that sold best that was the best music, or were there certain types of music, such as the symphonies of Beethoven, with inherent eternal values? Within what has been referred to as post-modernist discourse not only previous patterns of judgement were questioned but in addition all “grand narratives.” For instance, as early as 1987, in connection with popular music Simon Frith and Howard Horne wrote:

The historical moment of postmodernism is also the moment of the birth of rock culture, which is … implicated in many postmodern themes: the role of the multinational communication industry; the development of techno-logically based leisure activities; the integration of different media forms; the significance of the imaginary, the fusion of art theory and sales technique. Pop songs are the soundtrack of postmodern daily life, inescapable in lifts and airports, pubs and restaurants, streets and shopping centres and sports grounds (1987:5).

Postmodernism undoubtedly stood and stands for a (contemporary) way of processing and understanding the plurality of value norms and styles. What is what, “art music,” “popular music,” “folk music,” etc., has thus gradually become difficult to define, if possible to define at all.[42] There is no reason to believe that the Sámi as Norwegian, Swedish or Finnish citizens have not been affected by these relativistic trends in our societies.

Gradually Mari Boine’s recordings have become available as contemporary world music for listeners more or less anywhere in the world where there is an Internet connection. Her music affords all sorts of possible use and can thus be heard in many ways—as retaining a modern kind of Sámi identity in a global world, or as imploding or as a bridge over music-cultural borders or just as music.

The awareness of what it means to be Sámi varies a lot over the world and, of course, it is not even an easy thing to define for a Sámi person. It varies depending on factors such as age, education, gender, locality and profession.[43] Everyone’s identity, of course, varies depending on these factors and also over time and depending on the situation.

Without exception, all the Internet sites where Mari Boine's music can be bought today emphasise her Sámi ancestry. These sites often provide a kind of information and promotion in one. For instance, on the site www.themilkfactory.co.uk/music/mboine.htm it is stated about Gávcci Jahkejuogo that the compositions are “based on tribal percussions and acoustic orchestrations” and that they “reflect the polar conditions that are an integrant part of the singer’s life.”[44] Another example can be taken from a German site, nordische-musik.de:

The “tribal beats” from the most well known Sámi singer still creates music from the reservoir of folk, jazz and rock music, where Mari Boine admittedly has found a form of music that is her own. As usual, the Sámi lyrics make an impact as the Northern Norwegian Mari Boine sometimes whispers or adjures, or again yoiks with a full throat.[45]

From the time of her ethnic turn with Gula, Gula many have commented on the quality of her voice and her technique. Her style of singing was probably perceived differently among many of the younger Sámi generations and among those who had never heard yoik or a Sámi style of singing. What else could it be? My personal associations were more towards a mixture of Inuit and Native American singing styles.

Thus, it is common that journalists coming from abroad who write about Mari Boine after having interviewed her or who review her records make statements like Cronshaw, who wrote that few of the songs could be described as being in a traditional yoik form, but that yoik “is clearly audible as a fundamental in her music.”[46] The more well-known Mari Boine gets and the more people around the world who listen to her music, the more probable it becomes that listeners have seldom or never heard traditional yoik, which makes it difficult for them to assess whether her style of singing takes yoik as a point of departure or is inspired by it.

Recently, in 2007, Mari Boine herself wrote on the Internet that she at first “got in touch with yoik as an adult,” and that she gradually found various recordings of yoik in archives and found that it had different dialects.[47] Mari Boine’s way of yoiking is closer to the acculturated styles of yoik in the Southern Sámi areas, than to style of the Northern Sámi areas where se grew up. Mari Boine also writes that she is more interested in the essence of yoik than to copy contemporary yoik. She continues, “What I have found in the yoik is an existence … I have brought this into my music, also into the songs that does not sound so much of yoik” (ibid.).

To conclude: Whereas Mari Boine started out as a folk and rock singer, her music soon changed track into the world music scene. Her melodies are rather simplistic with few and sparse phrases, and contain few or drone-like harmonies. There is, however, a considerable breadth to the arrangements and the stylistic traits of the music on her later albums. The texts are often personal and existential, often referring to Sámi culture. Largely, Mari Boine has found her own style of singing and her voice is very personal, but her music has few direct roots in the Sámi yoik tradition. I find it thus increasingly problematic to label the music as ethnic from a traditional Sámi musical point of view. Arguments for the Sáminess of her music can arguably be information that blocks access to the music; as many listeners globally have found, these are great songs and simply great music. It is even easy to believe Mari Boine’s message in her own short song “Lottáš” in spite of that it is sung in her own “fake language.”[48] On the other hand, to other listeners, the perceived Sáminess is the platform from which their experiences of her music develop.

[6] An ambient yoik and art music world

The different socio-economic processes of change and the political climate in the 1980s and 1990s meant that the prerequisites for a general change of the self-identity of the Sámi population in the three Scandinavian countries have been different. Norway’s change into probably both the most egalitarian and most affluent country in the world has contributed to the possibility of the very large Norwegian Sámi population changing their social, economic and cultural conditions based on their own perceived situation. This can even be seen as a threat to the general society as Sámi ideas of self-rule, i.e., independence, have been expressed. Sometimes, in the press of Northern Norway, there are articles where Sámi nationalism is critically reviewed.

The Sámi population in Finland, on the other hand, is in a different position due to its few inhabitants. Here the Sámi are noticed to a lesser extent and they have little socio-cultural possibility to employ political power. Maybe it could be stated that the position of the Sámi population in Sweden from this point of view lies between that of the Sámi in Norway and Finland. The politicians of the general society in Sweden have had as their golden rule to step on the gas and the brakes at the same time regarding their standpoints on Sámi issues.

At the same time the percent of the Sámi population involved in traditional reindeer herding has decreased even further. Few Sámi families in Sweden can make a living exclusively by reindeer herding.[49] The symbolic importance of reindeer herding among both the Sámi and the majority peoples, though, is still stunningly great. Nevertheless, it cannot be denied that the living conditions of the great majority of the Sámi population are similar to that of their neighbours.[50] Moreover, during the last fifty years they have found themselves to be just one group of many “Others” in Scandinavia. In Sweden for instance, immigrant and refugee groups (Hungarian, Yugoslavian, Turkish, Chilean, Kurdish, Iraqi immigrants/refugees etc.) now amount to some 15% of the total population, i.e., some 1.3 million people to compare with 15,000–20,000 Sámi.[51]

* * *

Of course, there were many other Sámi yoik-singers, artists and musicians beside Valkeapää and Mari Boine at the time.[52] Coming from very different backgrounds, they used traditional yoiks as inspiration, or composed new songs and tunes (Cf. below). One of these musicians—less known in Scandinavia than Mari Boine—is Frode Fjellheim (born in 1959). He grew up in Karasjok in the north of Norway. His father is Sámi. Both his parents worked as teachers. Frode Fjellheim did not learn to speak Sámi, and even if he heard yoik in the community he became no bearer of this tradition himself. He was fond of playing the piano and later on, he moved south and studied for four years at the conservatory in Trondheim, Norway’s third largest city.

Consequently, it is no coincidence that the musical structures and arrangements on his first record were quite different from anything other Sámi musicians had done. He used yoiks in the southern style, taken from the transcripts in Karl Tirén’s book Die lappische Volkmusik from 1942, as melodic material for his own compositions, played by talented Norwegian musicians among his friends. The musical style of the first record, Sangen vi glemte—Mijjen Vuelieh (1991, Iđut, ICD911) and the second, Saajve Dans (1994, Iđut, ICD943), could be labelled as a fusion of jazz-pop-rock.[53] The overall complexity of the music placed it outside the boundaries of most music heard on the popular radio channels.

Among the more commonly used instruments are synthesizer, percussion, bass guitar and guitar, but on some tracks there are also oboe, saxophone, and flute as well as more unusual instruments such as crumhorn, harp, and Bulgarian bagpipe. Especially when recording the second CD Fjellheim wanted to connect more narrowly to the traditional sound and authentic expression of the yoik tradition. His aim was to create new and contemporary music inspired by yoik, and not like so many other Sámi artists/musicians at the time, to accompany traditional yoik in new ways.

Fjellheim’s music had no lyrics, but as a) it was stated on the sleeve notes on the CD that the themes of Fjellheim’s composition were original yoiks collected in the early twentieth century, b) that Fjellheim was Sámi, c) he often played at Sámi gatherings, and d) that the reviews and articles on his Sámi music where published in Sámi journals, it is more than likely that his music was heard as Sámi, especially by younger Sámi persons.[54]

It could be argued that the musical surface of Fjellheim’s music might have repelled many older Sámi listeners, who were not used to this type of instrumental jazz-rock, as with Valkeapää’s fusion of yoik/jazz/electronica. Nevertheless, it is more likely that the contemporary socially constructed process of Sámi-culture that surrounded Fjellheim facilitated the hearing of the musical structure as Sámi. Fjellheim’s music could be accepted and absorbed into the musical soul and bodies of Sámi people, old and young. Swedes and Norwegians who got to know about the music, often without hearing it, learnt to understand that Fjellheim’s music was Sámi.

The contents of the next production are well described by the title of the CD, Transjoik—throat jojik, shaman frame-drums, ambient sonics (1997, Warner/Atrium). On this album, the various solo instruments play a less prominent role. Instead, sound structures made by means of keyboards and computer-based recording and editing applications emerges in the foreground. The text in the liner notes explains in detail about the equipment used. Here is a lot of information that is probably more or less incomprehensible for most buyers of the album, alternatively things they did not have a clue they needed to know:

Synthesizer recordings, overdubs, sub-mixing and multitrack recording editing by frode fjellheim. … studioatrium uses beyer mc 740, 742 microphones… d&r merlin recording desk … modified roland dm-800 disc recorders … parallel phase frequency linerizing software was used during mix and mastering modes. This newly developed software features a non-destructive 24 bit editing … once the program was completed … the final 24 bit audio was transferred through an apogee uv22 cod encoder into the 16 bit cod medium.

As on previous albums, earlier recordings of Southern Sámi yoik play a major role as inspiring points of departure, but as on previous albums these recordings have been developed in various ways. One tune is stated as being a composition by Fjellheim, six compositions are made by the group in co-operation (“traditional/transjojk”) and two are compositions by named musicians in the group.

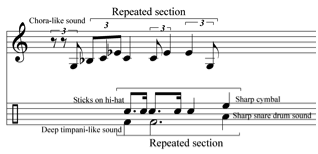

One of the simplest compositions is based on the vuolle “Sarek,” where an ostinato comprising the intervals c#-g#, d#-a# as fifths or fourths is played during most part of the song. Fjellheim sings the vuolle without the lyrics once, then in octaves with a bass clarinet, which is followed by a presentation of some of the motives on a flute and a bass clarinet. This goes on in different combinations. Now and then from 0:47 different percussion sounds take over completely: a) imitating the lowing of reindeer, b) deep thunder-like sounds, and c) indistinctive fast movements of a brush against a hard surface. Sudden bell-like sounds are also heard now and then, as well as sounds of the wind somewhere in the background, and additional deep bass tones that give the ongoing ostinato a harmonic colouring.

Another composition called “Gĺebrie” has a darker tone: at first, a human voice is heard yoiking in a South Sámi style on syllables in a constant movement of quavers (quarter note = BPM 72). This continues through most part of the composition. The rhythmical movement is supported by some kind of low percussion sound, it sounds again as if someone is banging a big shield of metal. Already at 0:08 a strange sounding motif is heard—two amplified double basses in a loud volume in a deep register. It consists of a half tone movement with minor thirds, e/c#–eb/c (on a half note) and eb/c–d/b (on a dotted whole not). Later on, some mystic short phrases on a flute follow (starting with a-g#-g#-b-g#-g#-g# etc. in semi-quavers). This spooky and threatening atmosphere dominates the whole composition.

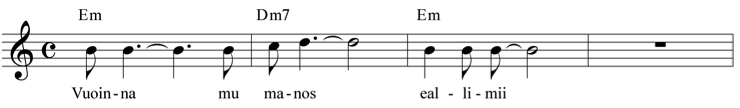

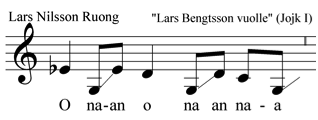

”Lars b. vuelle” is a third example, which at the time could be referred to as a standard Fjellheim composition. This composition starts with the sound of winds to a sampled yoik, “Lars Bengtsson vuolle,” performed by Anders Nilsson in 1913.[55] I call this section A:

Music example 6

At 0:09 a phrase on an instrument that sounds like a kora-harp picks up to a rhythmical accompaniment:

Music example 7

To these ongoing structures, a guitar-like instrument is added playing a short motif (on bb–c) that is reiterated in a non-synchronic manner. At 0:33 the first yoik is now also heard, but sung by Nils Olav Johansen. A second melody is simultaneously played on an instrument that sounds like an organ:

Music example 8

Soon long sustained organ-like tones are also heard in a high-pitched register. The yoik and organ melody stops at 1:02 and starts again at 1:14. The organ melody is now slightly altered. It all goes on until to 1:39, at which point a short excerpt of a second yoik is heard for a few seconds (this yoik excerpt returns four more times up to 2:19). [56] This part of the composition can be experienced as section B. At 1:46 long wavering notes are heard form a “flute,” first centring and ending on A2 and then on Bb2, and when the rhythmical groove and kora-phrase stop at 2:01, a kind of breathing also starts in the foreground. At 2:19, a slightly different rhythmical groove starts again, long notes from the flute continue and a third yoik excerpt is heard in the background. [57] At 2:49, a fourth yoik excerpt, lasting for two seconds is heard. [58] This yoik is heard four more times up to 3:23, where a third section C starts.

Here at 3:23 the first yoik melody is played by a flute to the accompaniment of a variation of the structures in music example. At 3:51, the flute-yoik is joined by Johansen singing the yoik two octaves below as well as the original version by Nilsson at 4:20 (yoik IV is also heard once at 3:30). The sound of wind blowing is added at the same time as the dynamics are increased. Before climax is reached at 4:39 even the breathing sounds are heard and they continue for a few seconds at the same time as the rhythm and accompaniment stop, and it just ends with a short second of a kind of C-minor-like chord in a high register.

Thus, the form follows an ABC pattern. This is a rather typical form that Fjellheim comes back to in his compositions, a long build up with different structures that are looped, varied, looped and so forth. In some compositions there tends to be no yoik samples at all, in others there are deep “archaic” voices that supposedly should lead the listener to imagine the sounds as referring to older Sámi times.

This record, then, definitely added to the stylistic width of Sámi music, turning it towards a different direction than for instance that of the music of Mari Boine. As indicated by the title of the album, it also features throat song of the Tuva kind. The dominating impression, though, is that Fjellheim and the group through this listening experience aimed at creating an ancient and maybe shamanistic dark mood, which rather would place the album on a shelf labelled Ancient world/Sámi/Ambient. It is surprising that it to a large extent was the producer of the record, Manne von Ahn Öberg, who took the initiative to change the sound of the record. It was actually he who had remixed the tunes and added sounds and instruments creating a new mood without the knowledge of the group. The band members were surprised over the result, to say the least, and it took time before they artistically had accepted the changes in full.[59]

The comments by a reviewer on one of the many commercial websites give a fair description of what is heard:

Fjellheim … primarily an electronic composer has assembled a band … to service something more than an ambient dance groove. Along with singers and joikers (shamanistic vocalists from the Sámi regions of Scandinavia), they have created a soundtrack of mystical technology and technological spiritualism. Like most music from machines, it can vary from plodding electro-acoustics to some inventive, unheard of sounds. This album scores better than most because the use of the acoustic instruments is very strong, especially the percussion. There is a heartbeat here that is usually missing from electronic experiences, and it drives the music home. Shrieking singers are in stark contrast to the joikers’ droning beauty. Droning saxophones meet waves of electronic wind. The beauty is bleak, the danger is sublime, the feel of Mahkalahke is one of confusion and mystery. (www.amazon.com/Mahkalahke-Transjoik/dp/B00000FYJK)

To what extent this album from 1997 transmitted any experience of Sámi yoik and culture, again in every aspect, depended on the background, connotations and listening style of each individual listener. Those who had the album could read the information in the liner notes. The word Sámi is only mentioned once there, but the word yoik is mentioned a number of times. Probably, the majority of Scandinavians associate yoik with the Sámi, but that does not mean that they know what traditional yoik is. The record was published by an international record company, Warner, on a separate label, Atrium. The label and the layout of the album signified that this was an artistic production of world music aimed at both the European and international market.

In the twenty-first century, Fjellheim, together with the group, has continued to produce trans-yoik music in a collective spirit and has also developed the music towards a world-fusion style.[60] Fjellheim has also composed music that clearly places him within the field of art music—an opera and a mass.[61]

On the album Transjojk, uja nami (2004, Vuelie, vucd804) there are only two tracks mentioned as being based on yoik. In a number of cases, the musicians taking part on this album are mentioned as composers in various constellations. There are a number of musical ideas on the record such as short repeated melodic phrases reminding somewhat of southern style yoik, but also of qawwali songs (Cf. below). There are also vocal sounds reminiscent of Inuit singing technique and in other cases of Tuva throat singing. There is usually a steady rhythm. Whilst most tunes can be placed within a broad ambient/ethnic field, there is also a quite traditional ballad and a fast techno-inspired song. Regarding the latter “Uja nami” (the name has no meaning) it is stated:

An original Transjoik tune from the Tjurrufabrikken rehearsals. Recorded live at Blast, Trondheim. The yoik sample is a backward playback of a vocal phrase yoiked by Piers-Per-Anne Rustin.

The name of the band, Transjoik, and the tunes on the 1997 record (Transjoik—throat jojik, shaman frame-drums, ambient sonics) often created connotations to shamanism and the state of trance of the Sámi shaman, the noid. However, the first element “trans” rather indicates a geographic connotation, i.e. that the group Transjoik is a trans-local band. With exception for the few, short samples of traditional North-Sámi yoik, it is only Nils-Olav Johansen’s style of singing that sometimes reminds somewhat of a South-Sámi yoik technique. To my mind and “ears,” the assertion that he sings in a “unique yoik-style” is in order as long as it is not alleged that he sings in a unique traditional Sámi yoik-style. That is not to say that as Johansen is not Sámi he cannot emulate a traditional southern singing style.[62]

The stylistic change that the group Transjoik demonstrates on the record Uja Nami is in a way consolidated on the next record (2005), which was made in collaboration with the group and the Pakistani qawwali singer Sher Miandad Khan.[63] Whereas there were musical traces of the qawwali tradition on the earlier album, that element is more obvious on this album as Khan is the lead singer on several tracks. It cannot be said, though, that the members of Transjoik have abandoned their special musical world, but, more accurately, they have clearly added another musical tradition. Whether the listeners perceive this as a successful amalgamation, a form of musical integration or musical syncretism, again depends on the reference frames and listening competence of each listener. Whereas the first song “Vuelkedh” to a large extent can be described as a “trans-yoik tune,” in spite of the fact that Khan is singing the most important phrase of the song, the second song “Mere dil de ander tu” is dominated by Khan’s traditional singing style positioning it within the qawwali tradition.[64] On this track, the rhythmical beat is an important musical element, which in fact is true for all the songs. It is hardly possible to give an overall classification of the music on the album as a whole. To start with, I would suggest “ambient/rock/dislocal yoik-style/electronica/qawwali.”

Maybe, using a metaphor from physics, it is possible to describe the stylistic abode of Mari Boine’s as well as Fjellheim’s et al.’s music as quantum-mechanic? The music exists everywhere and nowhere simultaneously, depending on the position of the listener and what the music affords the listener.[65] As is well known and will be further confirmed here this is not an uncommon musical phenomenon in our time.

The process of change I’m discussing has accelerated since the 1970s. To give a few examples, it was at that time was common to buy local music recorded on cassettes when you for instance as a Swede went on a holiday trip to Morocco. You might even have heard local music performed. Listening to the this cassette music later in your home in Sweden further changed the ways you could understand this music and its meaning. You might for instance have listened to it as you did the dishes thinking of your coming project at work.

Also, in the 1970s groups of musicians from Turkey and other countries came to Sweden as immigrants. Some of them, writes Roger Wallis & Krister Malm:

started to play individually with Swedish jazz and folk musicians. Within a short time Turkish folk music, Swedish folk music and jazz were merged into a new kind of music played in Sweden. (1984:297)[66]

During the 1970s, moreover, transculturation, a new pattern of change was observed. As defined by Wallis & Malm it meant a pattern of change whereby the music from the international music industry interacted with local music from other music cultures “due to the worldwide penetration attained by music mass media” (ibid., 301). In the 1980s there were also thoughts about a merge of styles into a global popular music style. But as Tylor Cowan recently has emphasized, what globalization tends to do is to increase difference, at the same time as it liberates difference from geography.[67] The amazing development of the Internet during the following decade and the downloading possibilities of all kinds of music by those connected to the Web have drastically altered the scene. In the connected world at least almost any kind of music can thus be understood as both globally accessible but used locally. As use, function and meaning of music interrelate it has become almost impossible the predict music’s affordance. This will be more evident as we proceed to our next case and the situation in this century. Thus, as I have hinted—where world fusion or any kind of music today locally should be positioned often escapes us.

For Frode Fjellheim and his group the question of what their music can afford the listeners and also what it should be called does not seem to be of particular interest. They produce what they apprehend as their own music and not primarily Sámi music, although often thematically inspired by South-Sámi yoik. The members of Transjoik were interviewed by the Norwegian radio in July 2007. Among many things, the latest stylistic changes were discussed. It was commented that it could be difficult for their audiences to label their music. At a concert a person with a funny voice asked: “Is it jazz or yoik?”—to which one of the band members commented: “I would say it is neither. It is music.”

[7] Avant-garde and yoik

The music and songs of the three Sámi artists Nils-Aslak Valkeapää, Mari Boine Persen and Frode Fjellheim can consequently be located in different places within the Sámi musical field. That can also be said about the music of a fourth important Sámi artist, Wimme Saari (born in 1959). Saari comes from the northwestern part of Finland. His mother had yoiked in her youth but gave it up as she became a confessor of the Laestadian faith. On one occasion, Saari yoiked in a dance hall when he was only 16 years old. However, it was not until he started to work at the Finnish Broadcasting Company in 1986, where he found some tapes, among them his uncle’s whose yoiks had been recorded in 1963, that Wimme Saari got really interested in the tradition.[68]

In the 1990s, he started to collaborate with the Finnish reed player Tapani Rinne and made recordings together with his group RinneRadio.[69] It is likely that the music of the group surprised most “normal” Sámi listeners. The stylistic span of the group is incredibly broad. Some compositions remind one of an ethnic Weather Report-music of sorts, with elements of quiet yoik-like tunes, whereas other tunes are played in a frenzied techno style with a stirring yoik-like song style. Other compositions are made in an avant-garde jazz style. Wimme Saari gradually developed a rather free position towards the northern Sámi yoik tradition developing it into a kind of voice art based on traditional yoik technique. It has been called “free yoik,” which means that his yoking on many of the early albums do not sound traditional. New metaphors and combinations had to be created to describe the advanced musical style of RinneRadio. For example, in a short review of their third CD (Cugu, ZENCD 3033) one reviewer in Rolling Stone wrote:

Wimme Saari sings a modernist variation of yoik … in which the guttural electricity of his animistic voice is enriched by snowfall keyboards, hearty woodwinds (blowing somewhere between free jazz and aboriginal drone) and seductive dance beats. The buoyancy of the music and the pictorial force of Wimme's cantorial singing erase any notion that he is selling out his culture. Cugu is colorful and honest fusion (Rolling Stone 2001:61.)[70]

Of course, it can, be doubted whether anyone can make sense of how these reed sound (“blowing somewhere between free jazz and aboriginal drone”), but as we will see, it is an unusually difficult task to describe this music. It should, of course, be heard.

The stylistic span on these records is always very wide. For instance, on the record Gierran (Enchantment, 1997) there are three tracks with absolutely traditional North-Sámi yoiks. One composition, “Havana,” is a delightful yoik-song, which is accompanied by baroque style bass and chords (”Gierran”). Many compositions are difficult to describe in brief terms and elude a clear-cut classification.[71]

To give a glimpse of the variety of the music, or rather the soundscape, on the record I will briefly describe what is heard on three of the tracks.[72] Take for instance the composition, “Iras” (Skittish) which starts off with a pulsating sound in quavers (BPM=138) from a synthesizer on the note A-flat to which Wimme Saari begins to hum softly (0:06) and then sings a kind of guttural short yoik motifs. Suddenly a short descending instrumental motif is played in forte. It sounds as if the motif is played on a “distorted” bass clarinet and a non-identifiable instrument (when variations of this motif is played an instrument sounding like a piccolo-flute is sometimes heard). This type of duet continues. At 0:47, a timpani-like percussion sound with reverb is heard and similar dull beats are added continuously alternating with other sharp percussion effects or synthetic percussion sounds. Wimme Saari incessantly continues with his stuttering yoik-motif, but after a while changing to the once-accented octave. In principle, this web continues in a similar fashion at the same time as the structure grows denser and becomes increasingly more intense.

Track 10 “Boska” (Angélica archangélica)[73] starts with a soft tone that grows in strength and somehow fathoms the whole soundscape. Wimme Saari enters very gradually by keeping long notes in a kind of Tuva-style (usually on E), simultaneously different instrumental sounds are added forming a dynamic carpet of sounds (often around E and B-sharp). The dynamics of this part increases and decreases until 4:45, when the undefined sound-structures from the synthesizer are given a rhythmical structure and is heard in the background as a carpet of sounds, at the same time as weak elongated notes (B-flat, A, and E) are heard and later high pitched pulsating, piercing, shrieking notes. At 6:17, weak sounds of voices are heard and then instrumental sounds form a double bass. The pulsating background sound diminishes gradually and goes away. At 7:02, only slow elongated notes in the second octave from Wimme’s voice are heard together with squeaking sounds in the third octave from unidentifiable instruments over a low-pitched drone. From 8:33, the soundscape is dominated of a fast, repeated phrase played on the bass clarinet, to which Wimme Saari little by little is heard making diverse sounds. Finally, at 10.01, it sounds like a cat meowing a last time.

The composition “Sámil” (The importance of moss) starts with the sound of bumblebees and birds and a simple monotonous tirade performed on a flute together with various bizarre voice sounds by Wimme Saari. For more than 6 minutes, there is nothing but silence (2:30–8:49). This is followed by quiet rain, and then Wimme Saari starts to yoik quietly for 30 seconds (at 10:01) and after another 30 seconds the rain and the composition terminate.

Describing the collaboration with his professional Finnish musicians, Wimme Saari explains that they build up a kind of soundscape to which he tries out different ideas.[74] The production of the music is an ongoing process until they decide that the composition is finished. This is similar to the composing technique used by Fjellheim and Transjoik. As a multitrack/multifile recording technique is employed, it is possible for the artists to move, erase or add different sounds/chords/motives etc., until they are satisfied.

If a concluding label should be given to the various albums Wimme Saari has been involved in, I would suggest “Sound art/electronica/ambient/techo/avant-garde jazz/yoik/hymn.”[75] Consequently, he has preserved the North-Sámi tradition of the area where he grew up, but maybe he is more important as an innovator. As he says in the article in the Finnish Music Quarterly: “The most important thing is to surprise yourself and the audience.”[76] His fan base probably primarily sees him as a Sámi yoik innovator. In contrast to Mari Boine and Frode Fjellheim I find less reason to consider the labels world fusion or world music. Just as the other artists mentioned, Wimme Saari has performed with great success in front of large audiences on various scenes in Europe and the USA. Due to these live performances, as in the case of Valkeapää, the attention of tens of thousands of listeners has been drawn to the music of Mari Boine, Wimme Saari and the music of Transjoik. In addition, the role of these three individuals as front figures is obvious. The importance of their performances for the dissemination and appreciations of Sámi music cannot be overestimated, and of course, even if you have not been able to attend any of their concerts you can now get glimpses of their performances on the Internet.

[8] Other styles—with or without yoik influences

We do not know whether or not the music and song performed today by Sámi artists are used in any way that differs from the use of other contemporary music. Neither do we know if the Sámi population in the world today, due to historical and socio-economic reasons, react to and use Sámi music differently than the surrounding majority of people

Since 1968 there have been Sámi musicians and artists who play and have published records within the wide fields of schlager, pop and rock, and where the lyrics have been in Sámi. In my opinion, the texts have gradually become less Sámi in the sense that they treat Sámi conditions: ideology, identity, and Sámi ways of subsistence to a lesser degree. Nowadays, the liner notes often contain a translation of the Sámi lyrics. It is clear that the music and songs discussed afford all sorts of use and thus can function in endless ways.

Since I published my compilation “Samisk musik i förvandling” (Sami music in transition) in 1989, at least forty CDs have been produced, excluding the records of the artists discussed previously. Most productions have received support mainly from Norwegian and Finnish government bodies and grant associations. The productions involve records with pure yoik and records with what can be generally called modern Sámi music. The start of a Sámi Grand Prix contest in 1990, in reply to the popular Eurovision Song Contest, has been of major importance for the continued interest in yoik and Sámi music. The Sámi version has two classes—yoik and modern song (with or without influences from yoik). Since 2001, the participants have been recorded to facilitate the publication of the songs on a CD.[77]

Because of the lack of distance in time, it is not possible to disassociate oneself from the material, which makes it difficult to get an overview over this vast quantity of music. This is further complicated by the fact that increasingly more music is published directly on the Internet, making it downloadable everywhere, at the same time as a certain song can become a great success for a short period within a local musical environment, being played and sung by locals, not the least among adolescents.

An attempt to catalogue the published production shows that from the 1990s there are groups and artists that sing and play in a style close to Anglo-American pop, where the original melodic material can be yoik and/or own songs. For example, here are recordings featuring Marit Hćtta Řverli,[78] Irene ja Tore,[79] Deatnogátte Nuorat—Buoremus,[80] Niko Valkeapää,[81] Vajas,[82] Lars Ánte Kuhmunen,[83] Lars-Jonas Johansson,[84] Idja,[85] Berit Oskal,[86] Sofia Jannok,[87] and Adjágas.[88]

Another group of musicians and singers more often combine yoik with traits of electronica and world fusion. Examples are CDs featuring Aŋŋel Nieiddat/Aŋgelit,[89] Orbina,[90] Johan Anders Baer,[91] Calbmeliiba,[92] Johan Sara Jr. & Group,[93] Vilddas,[94] Sáivu,[95] and Ulla Pirttijärvi.[96] Of course, there are also musically “pure” rock bands, techno bands, rappers and rap groups that all perform their lyrics in Sámi.[97]

As in most other technologically advanced cultures today, it is possible to find Sámi musical performances and record productions that are highly professional on the Internet. To what extent the audiences, as previously discussed, will experience these performances and records as emblems of Sámi culture will vary. On the other hand, especially on Youtube and MySpace, there are many short excerpts of yoiks recorded on mobile phones and also songs of different types by Sámi youth. It could be a short yoik performed by a slightly drunken man in a pub[98], humorous samples of Lappin Rappin[99] (www.myspace.com/lapinrappin) or a yoik performed by a young Sámi girl performed in a snowy field somewhere.[100] After having spent many hours clicking on different music examples and videos on YouTube and MySpace it seems as if you can find anything from the most bizarre to the most natural. Of course, nobody can know if there is an overproduction of yoik and Sámi modern music, but at least it can be established that the distribution is a problem.[101]

Naturally, due to the size of the population, contemporary Sámi culture is less multifaceted than the general Swedish, Norwegian or Finnish cultures. The Sámi population is smaller and consequently the culture has less qualitative musical peaks. It is clear that this is a culture existing in the shadows of the general Scandinavian culture, which is not the least evident because of the many contradictions within Sámi culture. On the one hand the Sámi composer John Person assiduously composes complicated modernistic art music, with a clear connection to European art music.[102] On the other hand, album after album with traditional yoik is produced, such as Davvi Jienat—Boazoolbmuid luođit (Northern voices—“Yoiks of the reindeer people”), a result of a joint project under the wings of the Nordic Sámi parliament. This project also resulted in an impressive book written in Sámi with interviews on the importance of yoik. Here statements can be read that recall what earlier informants in the nineteenth and twentieth century have said, but also remarks on the ongoing change. As one of the informants, Olof Päivio, says now much has changed:

Earlier on I always joiked. But joik now has changed in every way. They tell with a different form of music. Nowadays it seems to be the same melody all the time. Earlier you could recognise if it was someone’s yoik—today I do not think this is so. Now they only sing—that is not to yoik (Skaltje 2005:39f).[103]

All the other musical styles discussed in this article are thus located between these two positions—modernist art music and traditional yoik.