Motivic Identity and Musical Syntax in the Solo Wind Works of Åke Hermansson

Steven Harper

1. Introduction

Åke Hermanson’s music is highly concentrated, rugged, and abstract, retaining, in the words of Rolf Haglund (1980), “something of the harshness, the rough, rocky landscape and the wide maritime horizon of his native Bohuslän” (517). This is clearly evident in the five pieces for solo winds: Suoni d’un flauto, op. 6 (for alto flute); Alarme, op. 11 (for horn); Flauto d’inverno, op. 16 (for bass flute); Flauto del sole, op. 19 (for flute); and Nature Theme, op. 26 (for oboe), all of which resonate with nature allusions. These pieces constitute a unified body of work, with many materials and techniques in common.

In approaching these pieces, the challenges for the analyst include: 1) making associations between ideas, thus, overcoming the sense of isolation that each gesture acquires in Hermanson’s hands; 2) separating salient associations from non-salient ones, which is difficult because, as we shall see, his motives are so abstract and small that while one might first perceive the surface of the music as an incomprehensible jumble comprising a multitude of unconnected fragments, one can easily start to see an incomprehensible jumble of associations; and 3) identifying how these salient associations operate in larger contexts. There are three main keys to solving these difficulties. First, we must recognize that Hermanson’s motives are fundamentally unlike those in most music we encounter; they are conceived in terms of broad types, rather than specific, concrete entities. Second, we must recognize that Hermanson often employs patterns of motives, but these patterns are malleable, allowing for variation and modification of the individual motives, as well as the pattern itself. Third, we must recognize that these motives operate on a background of larger harmonies; motives can, thus, become linked by belonging to the same underlying chord. In this essay, I will discuss Hermanson’s motives and how they are constructed. Then I will show how larger units are created through motive grouping and harmonic prolongation.

2. Motivic Identity

Categorization and Musical Motives

In his book Conceptualizing Music, Lawrence Zbikowski relates specifically musical cognition to cognitive processes that have a more general application. Among the most basic cognitive processes is the process of categorization. In categorizing things, we assert connections between them; in other words, when we place two things in the same category, we recognize that the two things are in some sense the same. And, of course, once we have useful categories in our repertoire, new items can be placed in them. Category boundaries are neither given (they are created by the knowing subject) nor are they immutable (we constantly adjust our understanding of what constitutes a category) (Zbikowski, 2002, 30–32).

Zbikowski points out that research by Eleanor Rosch and others has revealed that while most of our commonly-used categories are arranged hierarchically, the process of categorization does not begin at either the highest level of the hierarchy, with very broad classes like “organism,” nor at the lowest level of the hierarchy, with individuals, like “Olof Palme” (Rosch et al., 1976). Instead, we begin in the middle, with a broadly useful designation, like “person,” called the basic level. As Zbikowski points out, Rosch’s research shows that the basic level provides efficiency and informativeness; that is, the basic level differentiates somewhat broadly (thus making relatively few categories available for the choosing), but still provides useful information about the individual thing being categorized (Zbikowski, 2002, 32–33). Categorizing something as a “bird” is more efficient than categorizing it as a “purple finch” and more informative than categorizing it as a “living creature.”

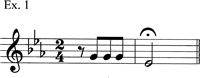

Motives in music generally operate at the basic level. They are not as large and encompassing as phrases, nor are they the smallest constituents in a musical surface, being themselves made of notes and rhythms. However, they are thought of as wholes, with immediately recognizable shapes and rhythmic profiles. Like other basic-level categories, musical motives admit of what is called a graded structure; that is, some ideas more clearly belong to the category than do others (Zbikowski, 2002, 36–41). This is usually the result of the construction of a prototype, a statement that tends to act as the comparison point for possible inclusion.[1] According to Zbikowski, a prototype for the category “motive forms for the opening of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony” looks like Ex. 1 (from mm. 1–2). Surprisingly, perhaps, this is not the most frequent version of the motive presented; there are more motive presentations at softer dynamics than at loud ones and more motive statements are presented in a single instrumental part rather than with the full orchestra. Nevertheless, there is a lot of specificity about the prototypical motive here, including a specific rhythm and a specific diatonic intervallic profile. Most musical motives have a prototype of this level of specificity. What we will find in the wind works of Hermanson is that this level of informativeness is not as available at the basic level for his idiom. Put another way, his motives (by being defined less specifically) tend toward a higher level in the categorization hierarchy, a superordinate level.

2.2 Hermanson's Basic Motivic Categories

Hermanson’s motives in the solo wind works fall into four broad categories: 1) steady-state ideas; 2) arpeggiations; 3) flourishes; and 4) conventional motives, with the first two greatly predominating. We will also encounter some basic transformations of these types: 1) embellishments; 2) extensions; 3) fragments; and 4) hybrids.

2.2.1 Steady-state Ideas

A steady-state idea is one in which a single pitch is employed in a passage. The prototypical steady-state idea involves two or more consecutive iterations of a pitch. Hermanson often makes the steady-state more obvious by having all the iterations be the same length. Steady-state ideas and their transforms represent a huge proportion of the music of the solo wind pieces; a particularly good example occurs near the beginning of Alarme (Ex. 2). In mm. 3–6 we have four statements of F4.[2] All of them last eleven sixteenth notes in duration, with single sixteenth rests separating them; all have an accent mark on the second eighth note of the duration (that is, the note is attacked, then pulsed without articulation).

All sound excerts are from the CD “Åke Hermansson Alarme” (Caprice 22056), used with kind permission by Caprice Records.

Steady-state ideas also are found with rapid rearticulations (that is, with iterations in short durations). Example 3 is a passage from Nature Theme that illustrates this kind of steady-state motive. These rapid rearticulations of steady-state ideas are found particularly in Suoni d’un flauto, Flauto del sole, and Nature Theme. Hermanson does not use this technique in Alarme or Flauto d’inverno, which are the starkest of the five pieces.

2.2.2 Arpeggiations

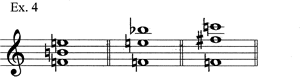

We cannot define arpeggiation gestures without elucidating Hermanson’s harmonic language to some extent; obviously, the notion of “arpeggiation” is tied to the notion of “chord.” Hermanson’s harmonic vocabulary (especially in these works) generally favors interval classes 1, 5, and 6. Furthermore, ic 1 tends to be represented by ints. 11 and 13, rather than by int. 1. The result is that most of the harmonies for these works resemble the chords shown in Ex. 4.

Furthermore, the idea of chord arpeggiation necessarily involves a notion of “voice.” When multiple voices are asserted, one must explain whether intervals represent motions within a voice (intravoice) or motions between voices (intervoice). As a generally applicable rule, we have the proximity principle of voice leading, which is discussed at length by Olli Väisälä in his work on atonal prolongation (Väisälä, 2003, 70–72). The proximity principle asserts that the closer two notes are, the more likely they are to be perceived as being in the same voice. In tonal music, steps are intravoice motions, while skips are intervoice motions. Generally speaking, in atonal contexts melodic intervals 1 and 2 (the semitone and whole tone) are still likely to be heard as belonging to the same voice, while int. 5 (P4th) and larger intervals seem to belong to different voices; intervals 3 and 4 (the m3rd and M3rd) can sometimes be heard either way. Hermanson’s more restrictive and more consistent use of intervals in these pieces makes these judgments easier than they might be for another composer’s music. Intervals 1 and 2 represent motion within a voice, while larger intervals (esp. int. 5 and higher) represent motions between voices. Moreover, ints. 11 and 13 represent motions between two different voices, with an implied third voice lying between the two notes of the interval.

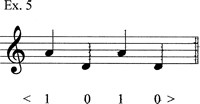

The simplest kind of arpeggiation is an oscillation. The prototypical oscillation contains at least four notes representing two pitches with a contour of <0101> or <1010> (Ex. 5).[3] An oscillation is most convincing if the notes are of equal duration, as the notes will be more likely to seem to have equal weight. Again, Alarme provides an excellent example near its beginning (Ex. 6a). In mm. 1–3 we find an oscillation between E5 and B4. There are seven notes; all are quarter-note durations except the last (which is a dotted quarter), and there is a strict alternation between the pitches. These pitches belong to different voices; the oscillation may, thus, be considered as implying a simultaneity (Ex. 6b). Oscillations are frequent in Alarme (where they act as iconic sirens), but are not encountered with any regularity in the other solo wind works.[4]

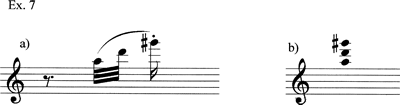

The simplest arpeggios to see are those that are unidirectional and involve ints. 5, 6, and 7, thus implying three “adjacent” voices. A clear example occurs in m. 16 of Suoni d’un flauto (Ex. 7). Where skips are larger, there are implied missing voices; Ex. 8 shows a figure from m. 13 of Suoni. There is a missing voice between G4 and G#5. The most likely candidate for the missing pitch is D5; four-note harmonies in which the lower two voices have a tritone and the upper two voices have a tritone (and the two tritones are T11 or T13 transforms) are often found in these pieces. However, no D5 is presented nearby, so this is just speculative based on other contexts.

A subtler example is found in mm. 4–5 of Suoni d’un flauto (Ex. 9). Here, a varied contour, <1210> is employed. The last three notes of the figure are a unidirectional arpeggiation, while the opening note acts as a kind of pick-up. There is a registral “gap” between D#5 and E4. Based on our knowledge of Hermanson’s harmonic practice, Bb4 might be hypothesized as a missing element. Bb4 is present both before and after the four-note figure in question, both times leading to A5, which is a member of the chord.

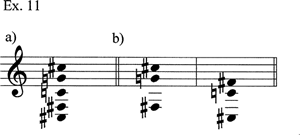

A more extended, complex arpeggiation can be found in Alarme mm. 25–30 (Ex. 10). Measures 25–27 present a three-note sonority, with a registral gap. Measure 28 fills that gap, then leaps to a register below. At this point we might hypothesize a five-note sonority (Ex. 11a). In m. 29 C4 returns, but it is followed by F#4, instead of G4. Motion within a voice signals a change of harmony, and it is likely that the most efficient analysis is actually to change harmony at m. 28; the chords of mm. 25–27 and 28–30 are similar (though not exact transpositions; Ex. 11b).

2.2.3 Flourishes

A flourish is, essentially, a rapid figure the effect of which is gestural. Flourishes must be contextually rapid. Example 12 illustrates some different kinds of flourishes. Example 12a, from Flauto del sole, is a rapid, unidirectional gesture. Example 12b, also from Flauto del sole, is an extended, unconventional twisting idea operating within a narrow range. And Example 12c, from Alarme, shows a quick arch shape.[5]

2.2.4 Conventional Motives

Finally, we have conventional motives. These are ideas that look like the kind of motives we are used to in music; in other words, these are ideas that have immediately recognizable shapes with a distinct rhythmic and intervallic profile, and that seem to operate on the basic level, rather than a superordinate level. On occasion, these motives can sometimes approach the status of leitmotifs; an example of this is found at the very beginning of Alarme (Ex. 13). This motive, which occurs three times in the piece, strikingly announces and conveys the sense of frightfulness that pervades this intense work. Because of its “dramatic” nature and function, I call it the “Warning” motive.

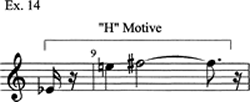

One conventional motive in particular is of special interest, since it appears in clearly in both Suoni d’un flauto and Alarme, and more subtly in Flauto d’inverno and Flauto del sole. I call this motive, shown in Ex. 14 (from Alarme), the “H” motive. Its characteristic features are the <012> contour, the relatively large interval at the beginning, the shorter opening note, the rising int. 2 that ends the gesture, the apparent metrical accent on the penultimate note (created by the shorter duration of the immediately preceding note, which, thus, sounds like an anacrusis), and the agogic accent on the final note. This motive seems to have special significance, in that it not only appears in four of the five pieces, it often appears with the same notated pitch classes as the ending, even though the sounding pitch classes would be different (e.g. E–F# in Suoni d’un flauto and Alarme), or with the same sounding pitch classes, despite having different written pitch classes (e.g., B–C# in both Suoni d’un flauto and Flauto d’Inverno). Example 15 shows some statements of the “H” motive. In Suoni d’un flauto and Alarme, the statements are presented so that a displaced semitone (int 11 in Suoni and int. 13 in Alarme) is followed by E and F# (Ex. 15a, b), despite the fact that the different transposition intervals of the alto flute and horn result in different sounding pcs (B-C# in Suoni and A-B in Alarme). In Flauto d’Inverno, the rhythm is smoothed out, so that the first two notes have the same rhythm (Ex. 15c); this is in keeping with the piece’s general lack of rhythmic jaggedness. In Flauto del sole, the motive is presented with a semitone between its “final” pitches, but in this piece the figure is routinely extended by yet another semitone, with the result that the E-F# found in Suoni d’un flauto and Alarme is filled in by a “passing” F (Ex. 15d).

Another motive, which approaches the status of an interval cell, is found throughout Suoni d’un flauto (Ex. 16). Its first appearance is in mm. 2–3 (Ex. 16a). The four-note idea uses intervals 6 and 13, and one pitch is reiterated (F#5 seems to be the main note for the passage, as it gets agogic accents). In its second appearance (Ex. 16b), we find ints. 6 and 11 and, again, a reiterated pitch. Here, the reiterated D#5 is shorter than the surrounding notes (allowing that E4 is perceptually longer based on there not being another note attacked for awhile after it). Its next appearance is in m. 6 (Ex. 16c). Here, the adjacent intervals are 11, 13, and 6; no pitch is reiterated. Now the longer notes are in the middle of the figure.

2.3 Common Modifications

Prototypical steady-states, arpeggios, flourishes, and conventional motives do not in themselves form the majority of the surface events in the solo wind works. But the majority of the surface events in these pieces are either prototypes or modifications of these basic categories. Essentially, we will be examining four kinds of modifications: 1) simple embellishments; 2) extensions (either prefix or suffix); 3) fragments; and 4) hybrids. The steady-state and arpeggiation categories, by being at the superordinate level, are most amenable to modification, and we will focus most of our attention on them.

2.3.1 Simple Embellishments and Arpeggiations/Steady-state

Hybrids

The most obvious embellished gestures are those that employ conventional embellishing tones written as grace notes. Hermanson uses these frequently to embellish steady-state ideas. However, these quick embellishing tones are not always restricted to a single voice; very often the embellishing note implies a different voice. When the main tone is presented both before and after the embellishing one, the result is a hybrid arpeggiation/embellished steady-state. An example from Alarme is particularly illustrative (Ex. 17). In mm. 7–8, C#5 is presented three successive times. The first statement uses a quick lower neighbor tone prefix, while the third employs a grace note from a tritone below (G4). The passage is an embellished steady-state idea, employing a simple embellishment and an arpeggiation embellishment. While these are clearest when the grace note is used, they can be found with embellishing tones that are not written as grace notes. Example 18, also from Alarme, provides an illustration.

2.3.2. Progressive Steady-state Ideas

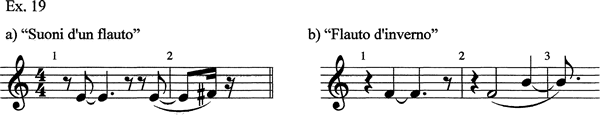

A very common modification of a steady-state idea is to add a suffix pitch to it. If that pitch is an int. 1 or 2, it is in the same voice and can be termed a progressive steady-state gesture. If the appendage invokes another voice, it becomes a non-oscillating steady-state/arpeggiation hybrid. Example 19 shows the two types. Suoni d’un flauto begins with a progressive steady-state idea (Ex. 19a). Two statements of E4 are followed by a much shorter F#4 as a suffix attachment. Flauto d’inverno begins with the non-oscillating steady-state/arpeggiation hybrid (Ex. 19b). Again, we have two statements of a main note, F4 (thus creating the steady-state foundation), and a different pitch of shorter duration is attached (in this case, B4, thus implying a different voice). In both instances, the continuation picks up from this new pitch; in Suoni d’un flauto this is an extended embellishment of the new pitch, while in Flauto d’inverno there is an intravoice motion in the new region.

2.3.3 Flourishes as Embellishments to other Ideas

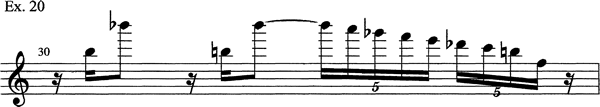

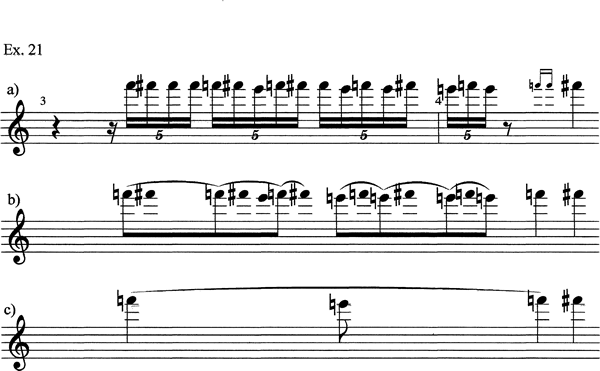

While a flourish may be a gesture unto itself, it may also act as an embellishment to another idea. Two examples from Flauto del sole are illustrative (Ex. 20). In m. 30, we have a B5–Bb6 dyad presented, with a falling flourish appended to the end. This falling flourish fills the space between the two main notes, then leaps further to F5, implying a three-note chord much like many others found in these pieces. The flourish in mm. 3–4 is more complex and especially interesting (Ex. 21). It hovers around F6 at the beginning, but can be interpreted as moving to E6 late in the figure before returning to F6 (written as grace notes) (Ex. 21b, c). Essentially, it seems that F6 is the main note for the passage, and is embellished before progressing to F#6 in m. 4. The flourish serves as an embellishment of a more basic idea.

2.3.4 Fragments

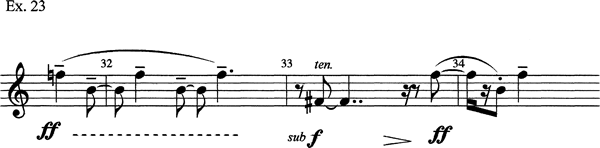

The two steady-state/arpeggiation hybrids (oscillating and non-oscillating) are difficult to distinguish from arpeggiation fragments. Context usually determines the preferred analysis. Consider an example from Alarme. The opening “Warning” motive appears three times in the piece; each time it is immediately followed by an oscillation. The first oscillation comprises seven notes, the second comprises five notes, and the third comprises only three notes (Ex. 22). With only three notes (in a <101> contour), we might be tempted to analyze this as an oscillating steady-state/arpeggiation hybrid; but the syntax suggests seeing these three notes as an oscillating arpeggiation fragment. In mm. 31–34 we find an oscillation between F5 and B4 (five iterations), a single note F#4, then a three-note oscillation between F5 and B4 (with the B shortened; Ex. 23). The previous oscillation, which gives F5 and B4 essentially equal weight, encourages a reading of this three-note version as a fragment.

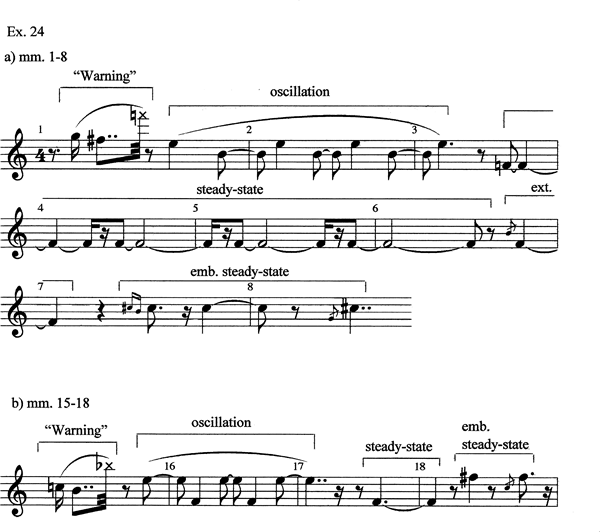

2.4 Analyzing Singletons and Dyads

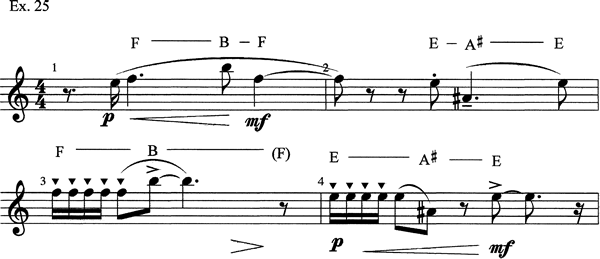

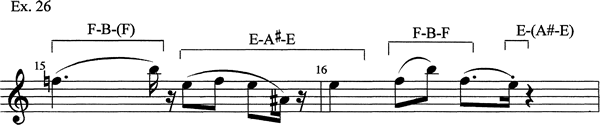

Hermanson’s solo wind works are full of singletons and dyad gestures. There is nothing illogical about viewing singletons as steady-state fragments (without a second iteration, they cannot be steady-states properly) and dyads involving two voices as arpeggiation fragments. Indeed, in some cases, these readings are fairly strongly supported syntactically. In Alarme we have already mentioned that the opening “Warning” motive is always followed by an oscillation. That oscillation, in turn, is always followed by a steady-state on F4. But while the first and third versions of this motive pattern utilize long steady-states (four iterations of F4, each eleven sixteenths in duration), the second sequence uses a singleton F4 (lasting ten sixteenths in duration) to represent the steady-state passage (Ex. 24). In Nature Theme, the opening measures present two tritones, F5–B5 and E5–A#4, with a prominent semitone linking them. In m. 3, the arpeggiation does not return to the opening pitch; this dyad still represents the “chord” (Ex. 25). In mm. 15–16 we have a passage reminiscent of the opening in which dyads and even singletons represent arpeggiation fragments (Ex. 26).

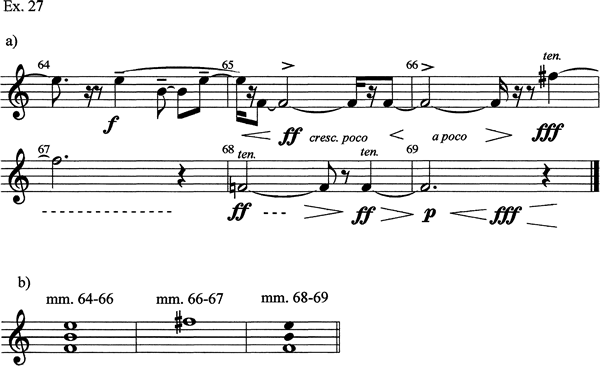

Another example can be found at the end of Alarme (Ex. 27). In mm. 64–65 we have an oscillation fragment E5–B4 followed by a steady-state F4. These three notes form a harmony utilized several times in the piece (including in mm. 1–7). The F#5 has most prominently been employed in the piece as part of the “H” motive; that progressive intravoice motion, implying a new harmony, is the context in which one should perceive the F#5 in mm. 67–68. F4 returns to end the piece.

3. Motivic Syntax in the Solo Wind Pieces

The essence of motivic syntax in the solo wind works involves the creation of larger patterns, themselves subject to variation and modification. As we mentioned earlier, one’s first impression of these pieces might be one of extreme disjunctiveness, but larger patterns can be found in all of the pieces. In this section, we examine passages from each of the five works.

3.1 Suoni d'un Flauto

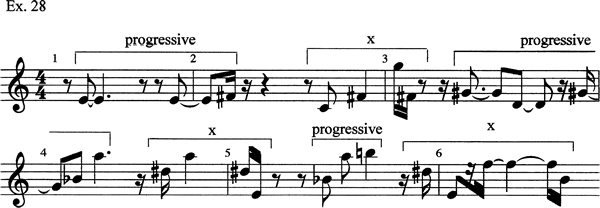

Example 28 shows the first six measures of the piece. Measures 1.1–2.1 contain a steady-state progressive idea. This is followed in m. 2.3–3.1 by a statement of the “x” idea discussed above. Measures 3.2–4.3 present a progressive steady-state on G#4–Bb4 with an arpeggiation to D4 between the G#4 statements and a further suffix extension to A5. The opening G#–Bb of this idea extends the whole-tone motion initiated by the first gesture. This is followed in mm. 4.3–5.1 with another “x” statement. In mm. 5.2–5.4 we have our “H” motive, which is a progressive idea (in that it ends with a rising int. 2); the beginning of the “H” statement re-presents the ending of the previous progressive idea in m. 4. This is followed with another “x” statement. Thus, in mm. 1–6, we have the pattern: progressive-x; progressive-x; progressive-x.

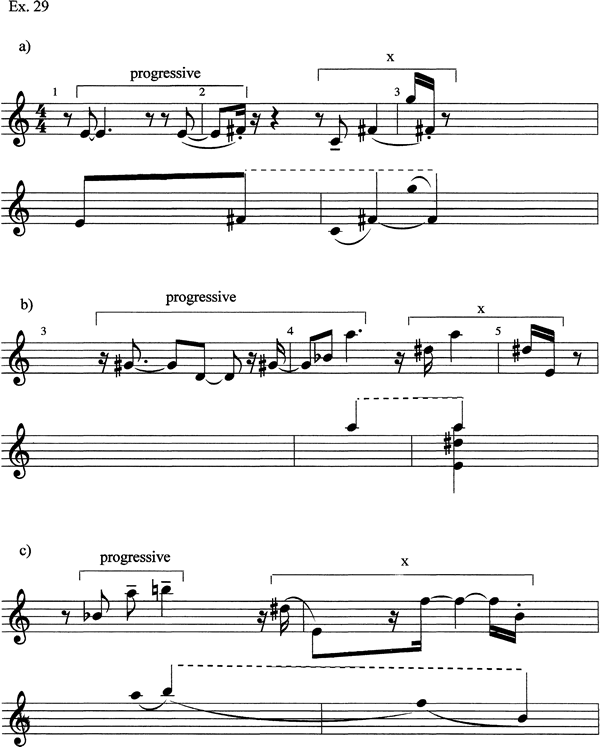

The progressive ideas link both to the “x” motives that immediately follow and to the next progressive idea that follows that “x.” Example 29 shows the connections from the progressive ideas to the “x” motives that immediately follow. In each case, the “progressive note” (the last of the idea) is featured in the following “x.”[6]

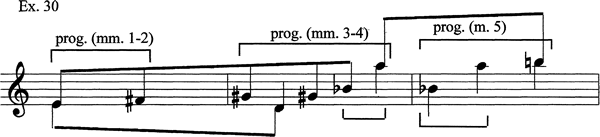

Example 30 shows how the three progressive ideas of the passage themselves link to one another. In the first two, there is a wedge-like structure, with the rising whole-tone strand more prominent. From the second to the third, the last two notes of the second idea become the first two notes of the third idea.

The passage includes three lines of rising int. 2s in three distinct registers (Ex. 31). Example 31 shows a hypothesized C#5 to initiate the middle register. I do not want to fully assert the implied presence of this note, but, instead, to show the basic harmonic structure in a fuller setting (we have already remarked on chords of this type).

3.2. Alarme

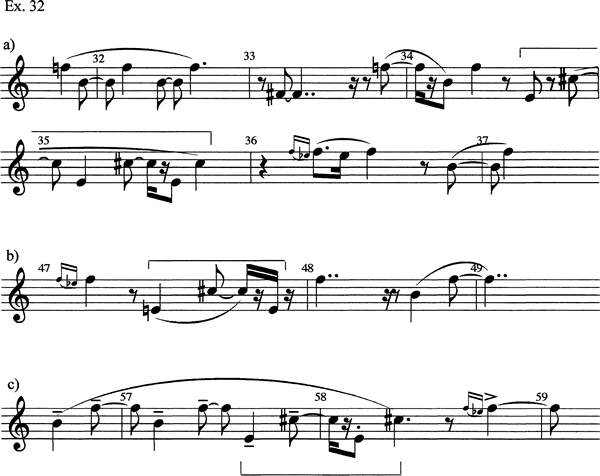

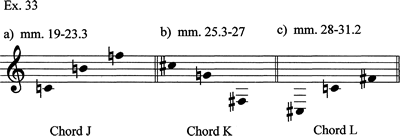

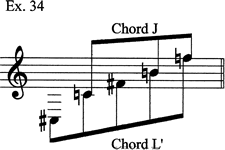

Hermanson mostly employs ints. 2, 6, 11, and 13 in this piece. But one recurring gesture employs int. 9: the E4–C#5 oscillation. There are three statements of this gesture (mm. 34.3–35.4; mm. 47.2–47.4; and mm. 57.3–58.3). Example 32 shows these statements and their surroundings. In all three cases, these motives are surrounded by F5–B4 oscillation fragments. The C#5 embellishes the B4 as an upper neighbor tone; but what is the harmonic origin of the E4? In mm. 19–23.3 we have three pitches that could be placed together in a sonority (Chord J in Ex. 33). In mm. 25.3–27 we find the sonority labeled K in Ex. 33; in mm. 28–31.2 we see chord L. At m. 30.4, F#4 is embellished with a grace note C5, an octave transfer of C4. At m. 31.3 we begin an F5-B4 oscillation, which is interrupted by an F#4 move down to E4, but there seems no viable way to imply this for the other passages (where F#4 does not appear). The E4–C#5 dyad sticks out in Alarme (here, int. 9 is a contextual “dissonance” that “resolves” to the more stable F5–B4 tritone). The voice-leading explanation requires seeing F5–B4 as a partial chord, with C4 the implied third note.[7]

3.3. Flauto D’inverno

While Göran Bergendal (1981) has noted Hermanson’s predilection for whole-tone elements, among the features of the solo wind works is his distinct preference for WT-1 passages (WT-1 is the whole-tone scale that has a C# in it); the form of Flauto d’inverno plays upon this. The piece is in six sections. The sections are distinguishable by the scale being used and are separated by the longest rests in the piece. The six sections form a repeating scale-use pattern of WT-1 (A) and chromatic (B). The sections are A1 (mm. 1–10); B1 (mm. 11–16); A2 (mm. 17–25); B2 (mm. 26–38); A3 (mm. 39–52); and B3 (mm. 53–70). Below I examine A1 and A3.

Both A1 and A3 begin with a progressive steady-state idea using F4 and B4 (Ex. 35). In both cases, this is followed by an idea centered around C#5. In mm. 3.3–6.2 this idea is a singleton C#5 with a grace note B4, then an Eb5–A5 tritone and another C#5 singleton; in mm. 42–44.2 it is a steady-state/arpeggiation (C# is embellished with a tritone in both segments, but the later one is more tightly constructed (and shorter) because the tritone includes the C#. The remainder of A1 is two statements of a variant of the “H” motive (encompassing a tritone, with the intervals +4, +2, F5–A5–B5), followed by a progressive motion to C#6. The remainder of A3 has a similar idea with the first interval expanded to +6 and a tritone appended to the C#6. The F5–B5 tritone is the main element in both passages, with with C#6 attached to B5. In A3, G6 is, in turn, attached to C#. One might also see mm. 42-45 as being derived from mm. 6-8, while mm. 45-48 as coming from mm. 46 (in other words, a reversal of the ideas positions; Ex. 36).

3.4 Flauto del sole

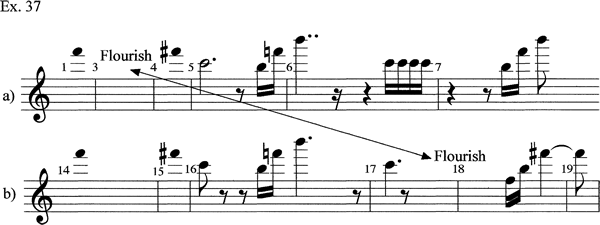

The passages I wish to examine in Flauto del sole are mm. 1–7 and 14–19 (Ex. 37). In mm. 1–4, there is a steady–state F6, followed by a flourish around F6 and a progression to F#6. In mm. 5–7.3 we have a steady-state C6, an arpeggio B5–F6–B6, a rapid steady-state C6, and a reiteration of the arpeggio. In mm. 14–18 we have a steady-state F6, an F#6 singleton, a C6 singleton, an arpeggio B5–F6–B6, a C6 singleton and a transposed and slightly extended version of the flourish from mm. 3–4.1. In other words, we have the same elements, but condensed and reordered. [8]

3.5 Nature Theme

Nature Theme has an exceptionally large amount of repetition and restatement. The first three (or six) bars return several times in the work. Here we will examine mm. 1–7 and a restatement in mm. 21–28 (Ex. 38). Measures 1–6 are organized around three tritones: 1) F5–B5; 2) E5–A#4; and 3) F#5–C6.(Measure 7 is not really a part of this group proper; it is the initiating gesture of a new group. However, its idea is modified in mm. 21–28.) Measures 20.4–23.2 are clearly derived from mm. 1–3. Measures 23.4–24.3 act as a stand-in for m. 4, but, of course, can also be seen as a stand-in for mm. 2.4–4. The sixteenth note F#5 is analogous to m. 5.1–6.1. Measures 25.1–25.2 relate to mm. 6.1–6.4, while mm. 25.3–25.4 reverse the pitches of m. 7. Measures 26–28 restate mm. 2–4, hitting the main notes. Again, blocks of material are reordered and subject to variation; it is primarily because the ideas themselves are so short and simple that the larger patterns are so difficult to perceive (hence the extreme concentration required of the listener).

4. Conclusion

Åke Hermanson’s solo wind pieces reveal certain aspects of his style that may be fruitful for analysis of his other music. We find that Hermanson’s motives are conceived abstractly, in such a way that they lead the listener away from the conceptual processes that are designed to focus on conventional motives (focusing on distinctive rhythmic/intervallic patterns), and more toward superordinate levels of categorization. The most important types of motives are steady-state ideas and arpeggiations. He further complicates matters by hybridizing and fragmenting these types; these hybrids and fragments actually comprise the majority of the surface events of these pieces.[9]

This superordinate-level motivic interest, when combined with Hermanson’s preference for varied restatement over direct restatement, largely accounts for the heightened concentration that his music demands from his listeners. Nearly every note seems to have special significance, which discourages grouping (a basic cognitive process). Group boundaries are smoothed over by category blurring, largely the product of hybridization and fragmentation. Listeners must then try to become aware of larger patterns (themselves subject to variation) that govern swaths of music difficult to retain in short-term memory without clear basic-level information.

But this abstractness is not simply a musical technique; it emerges from Hermanson’s overall aesthetic aims. About Invoco, Bergendal (2007) writes that it is “the first of a long series of compositions that are clearly about calls over long distances over time and space, and in some way directed at some higher power: Bohuslänsk klagovisa, Appeller, Alarme, Ultima, Utopia, La Strada. The calls seem me-less, as if the composer was a medium with the duty to receive and relay them” (55). These messages would not be of a scale for human understanding, but larger, more abstract, more difficult, and more encompassing. The vastness of this scale seems always to be in Hermanson’s mind and music.

References

Phonogram

“Åke Hermanson: Alarme.” CAP 22056. The performers in the excerpts are Ib Lanzky-Otto, horn (Alarme), Manuela Wiesler, flute (Flauto del sole), Alf Andersen, flute (Suoni d’un flauto), and Gunilla von Bahr, flute (Flauto d’inverno).

Written sources

Bergendal, Göran (1981). Liner notes for “Åke Hermanson: Utopia and Symphony No. 1.” Stockholms Filharmoniska Orkester, Antal Dorati. CAP 1206. Trans. by Robert Carroll.

_____ (2007). Booklet for “Åke Hermanson: Alarme.” CAP 22056.

Haglund, Rolf (1980). “Åke Hermanson” in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. By Stanley Sadie 8:517. London: Macmillan.

Rosch, Eleanor, Carolyn B. Mervis, Wayne D. Gray, David M. Johnson, and Penny Boyes-Braem (1976). “Basic Objects in Natural Categories” in Cognitive Psychology 8: 382–439.

Väisälä, Olli (2003) “Prolongation in Early Post-Tonal Music: Analytical Examples and Theoretical Principles“ Studia Musica 23 Helsinki: Sibelius Academy.

Zbikowski, Lawrence M. (2002) Conceptualizing Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Notes

[1] Zbikowski actually discusses prototypes in terms of conceptual models. A conceptual model is a collection of related concepts, rather than a particular instance. (44–48)

[2] In all discussions in this article I refer to notated rather than sounding pitches.

[3] For an explanation of elementary contour theory, see Marvin and Laprade, 1987.

[4] Remember: the oscillation as described here is a variety of arpeggiation; alternations involving ints. 1 or 2 do not generally imply two different voices, and, thus, would not belong to the category.

[5] Again, the sparsest of the solo wind works, Alarme and Flauto d’inverno, do not rely on flourishes, Alarme having only the one illustrated, and Flauto d’inverno having none at all.

[6] This is, admittedly, more obvious in the first two instances, where there is a clear motivic parallelism.

[7] Hermanson, himself, drew attention to this unusual interval, pointing out that it is an iconic siren, that foghorn at Böttö (Bergendal, 2007, 64).

[8] We might have extended the analogy by including the arpeggio at mm. 18.3–19.1, which has pcs F and B, but is not an exact restatement or transposition of the earlier arpeggio; this variant is the “missing” statement from this rotation.

[9] A third category that is extremely important in Hermanson’s output is scale segments, passages of largely unidirectional stepwise motions. While highly prominent in his other pieces, scale segments are not major elements of the solo wind pieces.